Dina Baslan continues to tell the stories of minority communities in Jordan. This is the story of Zohrab Markarian, the personal photographer of King Hussein, mentioned with the title of “the guardian of the nation” in Jordan throughout 25 years and remembered by international community with the active role that he took in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. Principally defining himself as “Jordanian” Markarian says: “One day, I will return to Armenia, but after giving back to Jordan.”

Dina Baslan

dina.baslan@gmail.com

The late King Hussein, father of Jordan’s current King Abdullah II, was renown for a charisma that preceded him. Jordanians alike celebrated him as the guardian of the nation. The international community repeatedly commended his active role in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process. To an extent, King Hussein seems to have emanated a certain sense of trust that left a trace in people’s hearts.

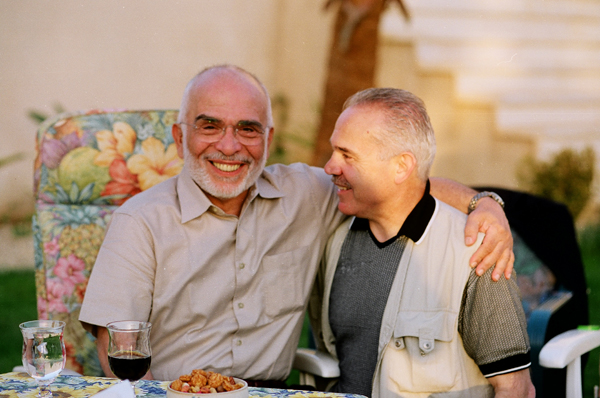

Zohrab Markarian, who worked as the deceased king’s personal photographer for 25 years, elaborately explains this trace. He says for him King Hussein was a king, a father figure, an employer, a role model, a drive.

“King Hussein…” he says staring outside the window of his studio in the capital Amman, “we died with him!”

The clean-shaven 59-year-old Jordanian of Armenian descends has had a nebulous relationship with identity since an early age. His parents moved from İskenderun to Amman without possession of official identification papers. Then when Zohrab was born in Amman, rather naturally, his parents didn’t feel the need to officially register their son. Zohrab remained without an official identity until he was 20 years old, when a passport officially validated his citizenship as a Jordanian.

Zohrab doesn’t speak much of his father. We know that he was an owner of a barbershop which was sometimes visited by members of the royal family, and that he lost a long battle to alcoholism at the young age of 38 which ended his life. Zohrab describes his grandparents as “poor people who suffered, who had nothing to offer but love,” and explains Armenians’ occupation dominance as craftsmen in Jordan by recalling his grandfathers’ advice: “if you learn a handicraft, you will never starve.” Zohrab adds to the aphorism with a hint of irony and sarcasm saying: “Maybe education will let you starve, but not handicrafts.”

So there he was, a 12-year-old young man faced with the reality of his father’s death, fed the collective wisdom of his forebears. He dropped out of school and started searching for a path to follow

“A very humorous man! An unbreakable charisma! How I wish I could smell him, hug him, kiss him!”

As he speaks about the king, Zohrab suddenly becomes extremely animated, and a reminiscent smile radiates from his face. “It is my love for King Hussein that brought me to photography – it was my only way to get close to him,” he says. Winning a photography competition and being named the king’s personal photographer, the royal palace became his working place, and he started accompanying the king on high-level trips around the world. “From Nixon to Clinton, I was there by the king,” he says.

In a country like Jordan, one gets accustomed to the ubiquitous presence of royal family portraits. It becomes commonplace. But not in Zohrab’s photography studio. There, you are haunted by the presence of large portraits of the king and his family, smiling back at you. Indeed, each photograph hangs as a testimony to the legendary journey Zohrab had taken by the side of an unforgettable man.

“I do things now because I owe him, and Jordan,” he says. “If I leave now I would feel like I am betraying him and his memory!”

Another memory stood stagnant for the longest time in Zohrab’s conscious, unmoved, until a group of passionate Armenian activists triggered an ethnic nationalistic sentiment buried deep within him. At a time when he was fighting a personal battle, it sent him off from the United States to the Caucasus, where he found himself holding his camera before an ugly side of the human face.

It was early 1990s and a war was being raged in Armenia’s fight for the predominantly Armenian-populated Nagorno-Karabakh enclave in Azerbaijan.

“I think it was April 1993; I remember the blossom of cherries, greenery everywhere, it must have been spring! The first day I arrived Stepanakert, the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh, it was being hit by bombs with jets. I went for a walk the next morning and saw homes destroyed. They were taking out pieces of things. I saw a small leg, with white socks, no blood on it. I thought it was a toy cut into piece. The man said it was a baby and I started to cry,” he recalls.

He remained in Stepanakert for two weeks, touched by a side of humanity he had not known before. Using the photographs that he took in his ancestral homeland, he held a photo exhibition in Los Angeles to raise awareness and money for Armenians suffering from the war. He was able to return to Stepanakert with $80,000, mostly contributions from rich Armenians in LA.

“It was a good, painful experience,” he concludes, “and it makes you real, to appreciate what you have.”

Ultimately, Zohrab says he considers himself a Jordanian before being an Armenian. 13 years after the death of King Hussein, Zohrab says: “Now I’m living with his [King Hussein’s] memories and will go on with life. His soul is around us. Nothing is gone. Jordan needs us now, and it’s time to give back.”

It is in Jordan where Zohrab took on the challenge to make a living and succeeded. He says it was hard building a name for himself in Jordan, but that it is even harder to maintain it. The key, as he sees it, is being true to oneself.

One day he thinks he will return to Armenia. “I love Armenia. I love its mountains. As long as I have a four wheel to drive me around, with my camera, I’ll be fine.”