Political documentary photographer Ali Öz, as he calls himself, is not currently working for a publishing organisation. But for a very long time, he has not needed a contract to record Turkey's social and political life. Ali Öz's photographic archive is full of images documenting the story of labour and at the same time recording all kinds of social actions in almost fifty years of Turkey's history. For Öz, who sees journalism not as a job, but as the main endeavour at the centre of his life, which motivation weighs more heavily: political responsibility, professional appetite or the desire to document?

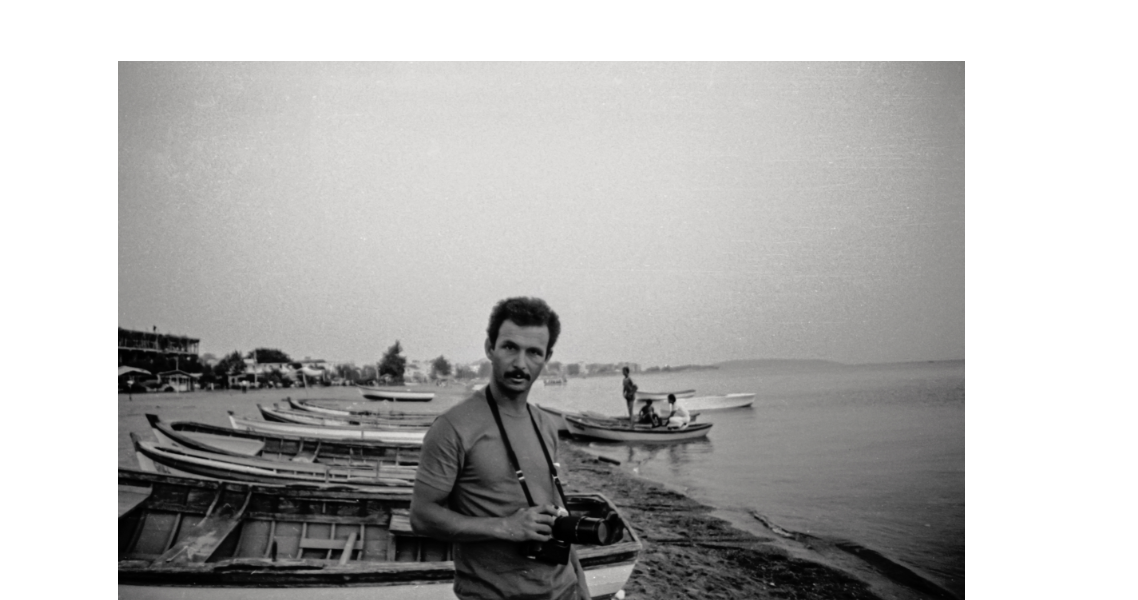

When choosing a day for an interview, it is important to look at where and what protests are taking place that day. Ali Öz, a journalist, photojournalist, political documentary photographer as he prefers to call himself in recent years, is not currently working for a publishing organisation. But for a very long time, he has not been required to work under contract in order to record Turkey's social and political life. Even when he worked for certain organisations, he prides himself on choosing his own work.

Almost half a century has passed since he first picked up his camera in the late 1970s. It is not easy to count them one by one; Ali Öz thinks he may have taken a million frames. A small part of this huge corpus, which is great in itself, has recently begun to be uploaded to the Salt Research Archive of City, Society and Economy. It will be a collection of 5 thousand frames in its entirety. A real public service.

“I need to slow down, too,” he says, “taking photographs non-stop, how much longer?” He made such a decision for 2025, but it was not possible to realise it. He counts the agenda of the last couple of weeks; the trees cut down in Kazdağları, the rally in Ankara, the new plans for the Belgrade Forests; he wants to be present at all of them as much as he can. In fact, we will meet with him, and then he will go to Beşiktaş Municipality. That very day, Mayor Rıza Akpolat was detained and there will be a demonstration in front of the municipality building. A person who had a serious brain disorder and was on Sıraselviler Street to follow the women's 8 March Night March as soon as he got out of hospital. He would not be comfortable if he did not go.

Ali Öz's photographic archive is full of images documenting the story of labour and at the same time recording all kinds of social actions in almost fifty years of Turkey's history. For Öz, who sees journalism not as a job, but as the main endeavour at the centre of his life, which motivation weighs more heavily: political responsibility, professional appetite or the desire to document?

"We are the people who writes a note for history, that is the main task. I have a class-based perspective that comes from my life," he says. The story that brought him here started with a rebellion against her father. His father, after divorcing his mother, had a second marriage and took him to live with together. What her father put her mother and sisters through over time, and the pressure he put on him, led him to rebel one May day, and he fled back to their village in Silifke and settled with her mother. In fact, this is how a child who grew up in the city, who does not know how to work on land, meets the difficulties and the consciousness of struggle that will spread throughout his life begins.

What his labourer mother taught him, his personal experience of what the moneylenders and merchants put the landless peasants through while working in the tomato fields, and then the period of awareness in high school when he caught a glimpse of the 68 generation... He says that he learnt about injustice by experiencing it, and since he was a child who loved to read, this is how his horizons were broadened. He had no role models, but it was during this period that he decided to pursue journalism, which he saw as an area of struggle against all this, and that year he won his first choice, Ankara University School of Press and Publications.

The shepherd who changed Ali’s life

We will continue his story through the frames we have selected from the archive. In 1978, when he became a participant of Köy-Koop, he got a camera for the first time in his life and started to shoot whatever he found around him with an appetite. His mother, people from his village, village life. The one we have chosen is a shepherd from his village. While she was still in school, she sent this shot to one of the competitions where she would receive many awards. Yazgülü Aldoğan liked this photograph very much and hung it in her room.

At that time, Ali Öz would be one of the three young people she invited to Istanbul for the upcoming Nokta magazine. That is why this is one of the photographs that changed the course of his life. In late 1982, when he arrived in Istanbul on a snowy day, he had nowhere to stay. He would not have been able to continue working at Nokta if “Sister Gönül, the trade unionist” had not hosted him in her house for six months.

Öz describes himself as a very confrontational person. The tension between him and the photo editor of Nokta magazine spread over a long period of time, leading to a rupture with the interruption of his military service. When he returns, he finds his employment contract terminated. It was 1985, and his days in Istanbul without a job and without money began. Not for long, Güneş and Milliyet newspapers, Aktüel and Tempo magazines, then Cumhuriyet, Star, NTV and Birgün. He says that he was "indispensable for the press" in those years.

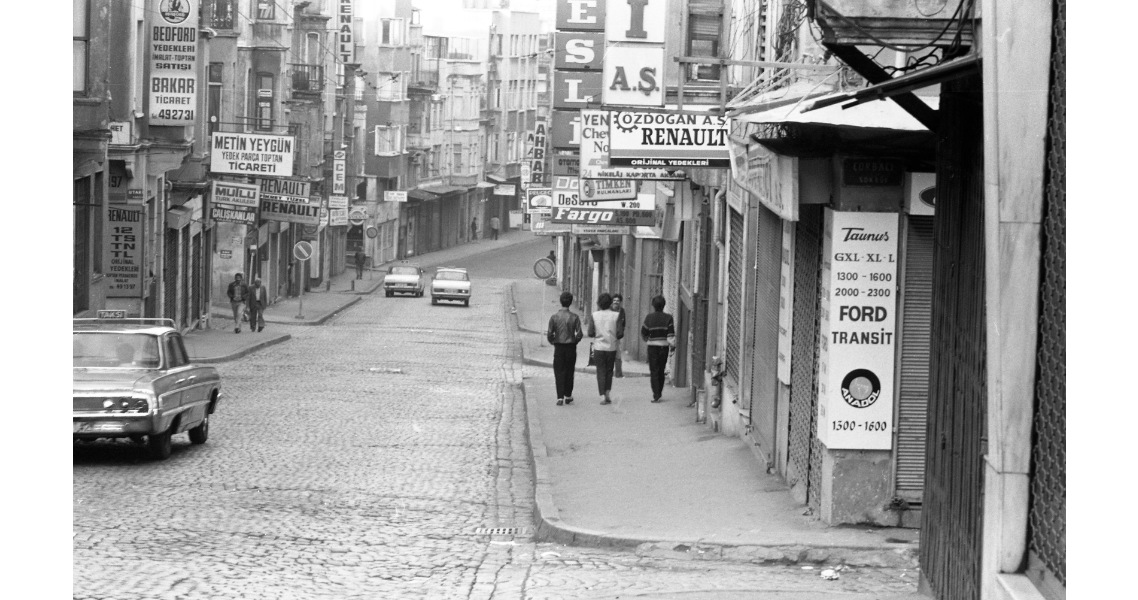

Tarlabaşı with its untransformable side

Documenting labour, production and labour processes in different sectors has always been one of Öz's priorities. The second photograph we have selected is from a trip to Buldan, Denizli in 1979, again within the framework of Köy-Koop's organising activities in Anatolia. Women workers in a textile factory in Babadağ. Women's labour has always been one of the topics he has always followed because of his admiration for his mother, from whom he says he received his knowledge of economics.

From here we connect to the third frame. He decides to go to Adana to film agricultural workers because of her mother, who spent twenty years of her life working as a cotton labourer. Even though he does not go with her, he wants to get closer to the stories of other ‘Ünzile’, even if they are not her own experiences. He reads the writings of Fikret Otyam and Yaşar Kemal. He will photograph cotton workers in Adana at other times, but in this case the year is 1981.

I wonder what his mother thought when she saw these frames? "My mum came to my Tarlabaşı exhibition, but I'm not sure if she saw these," he says. But he adds a cotton memory. His mother and sister got on a lorry and went to cotton. They want to leave her sister, who is quite young at that time, with her grandmother. When her six-year-old sister insisted, they had to take her in the lorry too. But at that age, how would a child know how to pick cotton, how to draw cotton? When she gets in the way of a male labourer, the man slaps her. "Blind bastard, why did you hit my child?" his mother shouts. The next morning they wake up and go back to the field, the man is blind. Öz continues the story that will extend to him as well: “My mum said ‘you blind bastard’ so sincerely that the man said ‘what have you done to me Ünzile’ in the morning. It's interesting, but I have it too, I've been struggling in Istanbul for forty years, whoever has done me evil has not remained normal.”

The fourth frame is again from a topic that he will follow throughout his photographic life, garbage dumps. The Ümraniye landfill he visited in 1986 will explode a few years later due to methane gas compression, and perhaps the people he met that day will lose their lives. Apart from Ümraniye, Kemerburgaz, Kazlıçeşme and Halkalı dumpsites are also kept in his archive in files. He also remembers the Bodrum, Gümüşlük garbage dump, but he wasn’t didn't allowed to film there. “It was unbelievable,” he says, “It could have turned out like Salgado photographs. Some photographs remain in my mind even if I can't take them.”

The photograph in Tarlabaşı, which we have chosen as the fifth photograph, is from 1987, but Tarlabaşı is a place he has travelled to throughout his life and documented its transformation. First of all, his first house, which he rented with a friend in the years he came to Istanbul, was in Tarlabaşı, so he is considered to be from there. He first started photographing as a neighbourhood resident. Then he recorded the extensions of various social events from May 1st to the Kurdish issue in that neighbourhood.

He describes the transformation of the neighbourhood as follows: “Actually, nothing much has changed. I think it has become a bit like Sulukule. They ruined Sulukule to make it a rich neighbourhood, but they couldn't do it. In Tarlabaşı, they are trying to sell the buildings they built on the roadside. No rich person would live there under those conditions. It will become offices, it will be sold to Arabs, but they failed to achieve the transformation they dreamed of. But this is important, the people there were forcibly thrown out of their homes. For example, there was Uncle Ahmet, he died of a heart attack during the last forced eviction. They especially gave way to thieves so that they could break into the houses and loot them. They moved the foundations of the buildings, many houses collapsed in front of my eyes.”

Times of artificial intelligence

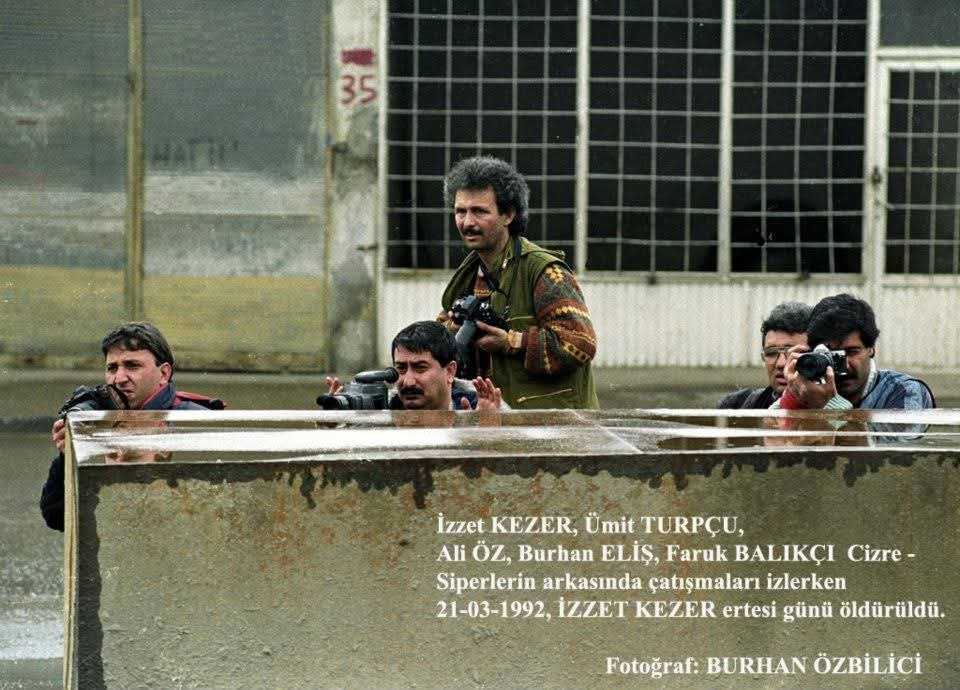

Apart from the Ali Öz photographs added to Salt's archive, this sixth frame taken by Burhan Özbilici can summarise what it was like to follow social movements in Turkey and to work as a news reporter in conflict zones for all these years. 21 March 1992, the Newroz area in Cizre suddenly covered in blood. İzzet Kezer, who appears on the far left of the frame, will be killed, Öz will throw himself into the terrace when the hotel is being raked, and his finger will be broken.

“Photograph was very valuable at that time, and they were afraid of it. Because it documented what was happening,” says Ali Öz. Today, it is necessary to think about the power of such documentary photographs. Images produced with artificial intelligence and the fact that this has become a systematic manipulation tool is of course one side of the issue. But the issue does not end there. For example, while genocide is going on in Gaza and there are still reporters there who risk their lives by taking photographs, in other words, while what is actually happening is documented, people may prefer to feel sad with images of genocide produced by artificial intelligence. A more dramatic, more effective frame is preferred. The truth itself is not enough to tell the truth; the record of the truth loses its credibility and power. What does he think about all this?

“I'm frankly very scared about the future. I look at a photograph, maybe it was developed with artificial intelligence, I don't know, because sometimes they can fool even me. My wife says that I wish all your photographs were delivered somewhere intact. Because if this archive falls into the hands of inappropriate people in the future, they can manipulate it as they wish. I want to hand over this entire archive and be free. On the one hand, photography has become a rich profession where people buy the most expensive cameras. Filters, this and that. I'll be frank, I spit on your beautiful photographs; I'm not going to take beautiful photographs. I'm a photographer who strives to convey the truth. For example, during the trench wars, I went there as an unemployed journalist. I shot as much as I could. As you can see, it is even more difficult to work without being affiliated to an organisation. I am a person who carries a permanent press card, but there is no organisation behind you to protect you. And yet I'm struggling. I don't know if there is such a man in the world, he has been telling the story of his own country for over forty years.”