The relationship between yayas born outside of Istanbul and the Armenian language was also highly intriguing. Some never learned Armenian, while others, speaking in local dialects, were shamed for it. The mistaken belief that Istanbul Armenian was the ideal and most beautiful version of the language played an active role in the rapid loss of these local dialects. The stories of our friends’ yayas in the diaspora are different from ours. The grandmothers of Armenians who migrated from Cilicia to the Aleppo-Beirut route or those who immigrated to the United States carry narratives distinct from those who remained in Turkey

TALİN SUCİYAN

As the Parrhesia Collective, we have been organizing online meetings for some time now under the name Kov Kovi [Side by Side]. For the past two months, these meetings have focused on the place of our grandmothers, our yayas, in our lives. Among us are young women in their early twenties, which means that our yayas belong to different generations. This allows us to reconsider what our grandmothers have meant to us from 1915 to today and to reassess their place in our lives.

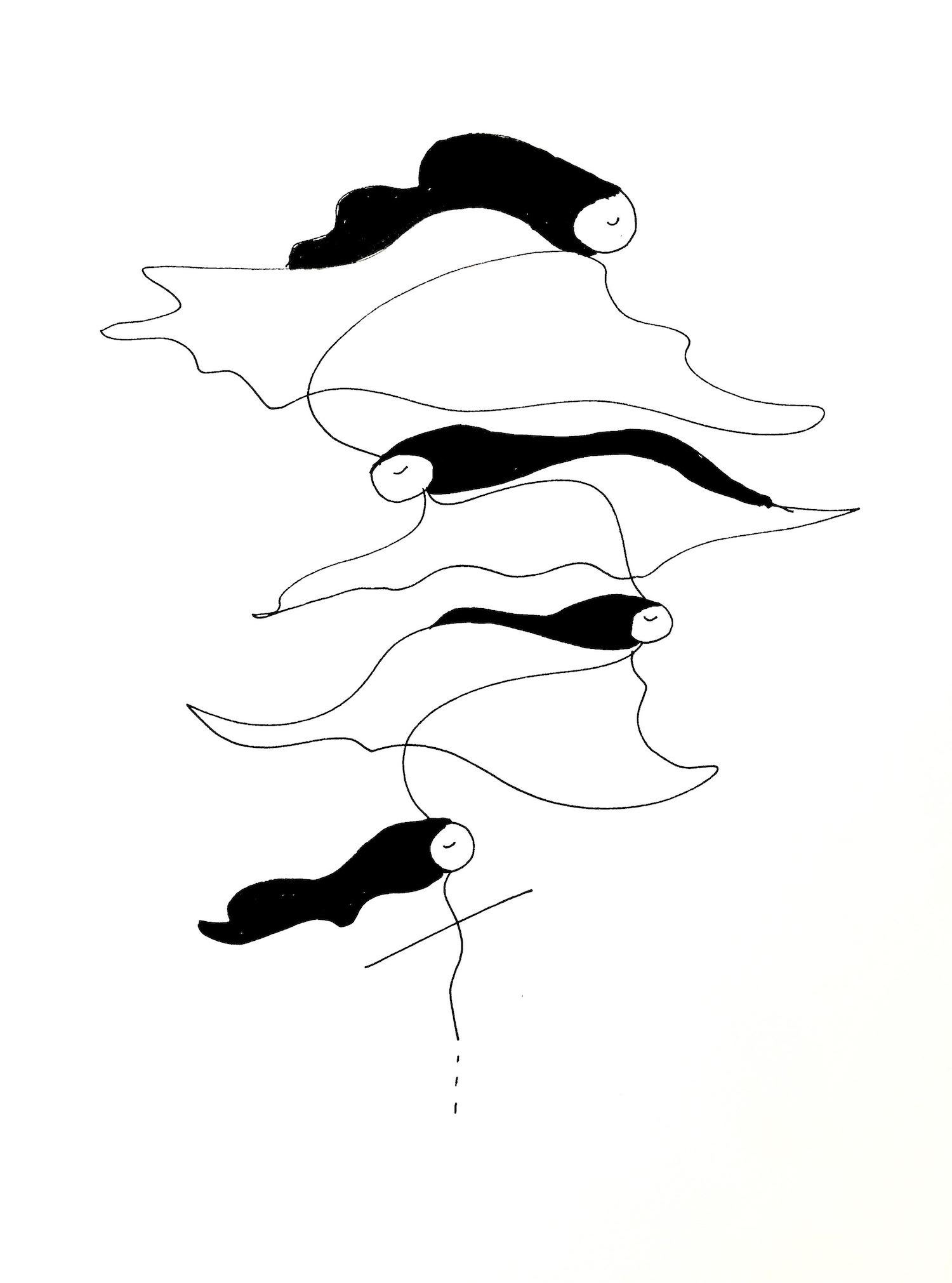

Walter Benjamin describes Paul Klee’s famous work Angelus Novus as the “Angel of History.” According to Benjamin, when the Angel of History looks back, it witnesses a chain of disasters piled upon one another. Yet, the winds of modernity and progress blow so forcefully that the angel cannot pause to piece together the shattered fragments. The storm propels it forward. Angelus Novus stands frozen in the face of catastrophe.

There are many reasons to think of our yayas as the angels of history. Their frozen state in the face of the catastrophes they endured, the lives built upon silence and the inability to speak about what had happened to them, fit precisely within Benjamin’s definition of the Angel of History. Particularly for yayas who were born and raised outside Istanbul after 1915, revisiting how they represented Armenian identity in their relationships with their grandchildren helps us better understand what they left behind. In the coming weeks, we hope to share the stories of the yayas of our young women friends in this space.

The relationship between yayas born outside of Istanbul and the Armenian language was also highly intriguing. Some never learned Armenian, while others, speaking in local dialects, were shamed for it. The mistaken belief that Istanbul Armenian was the ideal and most beautiful version of the language played an active role in the rapid loss of these local dialects.

The stories of our friends’ yayas in the diaspora are different from ours. The grandmothers of Armenians who migrated from Cilicia to the Aleppo-Beirut route or those who immigrated to the United States carry narratives distinct from those who remained in Turkey. We hope to welcome guest writers in this space to share their perspectives as well.

And then there are the yayas of those who are now in their forties, fifties, and sixties—women born during the time of 1915—who represented yet another reality.

And then there are the yayas of those who are now in their forties, fifties, and sixties—women born during the time of 1915—who represented yet another reality.

My yaya Iskuhi from Erzurum, my mother’s mother, was one such woman. As far as we know, she was born in 1915. We never knew under what circumstances she arrived in Istanbul. She had a twin, but she had died. Her entire family had been deported from Erzurum to Iraq, where they were forced to live as Muslims. Most of her family, including her father, had perished completely. When Iskuhi and her mother, Satenik, arrived in Istanbul, they had most likely lived in kağtagayans (centers where surviving women and children took refuge). Until today, I had never even put into words that Iskuhi had no father—that she was an orphan.

When she was married off to another survivor, Istepan, the first thing he did was change her name from Iskuhi to Silva. It is very strange that we never questioned this arbitrary renaming. Iskuhi was not a woman who held the reins of her life. She had survived, but her sense of self was too entangled to grasp. She lacked the ability to stand by herself, her daughters, or her grandchildren as a woman, a mother, or a grandmother. She could not defend herself or her children against her husband, nor could she be their source of support or protection. Perhaps she was the embodied weight of another disaster—one she could not name but carried all her life.

At the same time, in the absence of men, it fell upon these women to hold the family together. When I think about the place of the grandchildren of these solitary women in our lives, I cannot help but see them as representations of catastrophe. Even when they did not speak, the sight of them staring out the window for long stretches etched itself into our memories, serving as a lifelong reminder of disaster. While their entire existence became a mourning for the life, family, home, and homeland they had lost, they became figures in our lives and memories tied to an inheritance—one that was powerful yet heavy. An inheritance that demands understanding, remembrance, and the honoring of their memory in a way that befits them.

To discuss these issues and more, we will hold a webinar on April 2 with Lara Aharonian. Lara Aharonian was born and raised in Beirut, later migrated to Canada, and, after many years there, settled in Yerevan with her children and husband. She is a well-known women’s rights activist, particularly for her work against gender-based violence. As the Parrhesia Collective, we will talk with her about what she inherited from her yaya and her experiences as a woman born and raised in the diaspora who is now engaged in the struggle for women’s rights in Armenia. We would be delighted to see the followers of Parrhesiapar join us for our webinar.