It was by pure chance that the 25 Hagop Jololian, known by his pen-name Siruni, poet, journalist, and political activist, escaped arrest on April 24, 1915. On that fateful evening some 260 Armenian intellectuals of the Ottoman capital were arrested. Later, those intellectuals were deported eastwards in remote Anatolian corners, tortured and assassinated. The Ottoman state will soon send nearly all of its Armenian citizens to the Syrian Destert, to be killed, or to die of hunger, thirst, or of epidemics. Siruni would spend the next three years hiding in Constantinople, until the war ended and the Ittihadist (Committee of Union and Progress) leaders escaped to Germany.At the end of the war, when the Ottoman Empire was defeated and the Ittihadist leaders escaped to Germany, Siruni came out of his hiding, and with few surviving intellectuals tried to re-establish a community that was mortally wounded.

From among those deported was Taniel Varoujan the great romantic poet of the Armenians. They had met in 1912 when Varoujan returned from Europe, and started intense collaboration, organizing cultural evenings and publishing together the literary periodical Navasard. On the 25th commemoration of the Genocide in 1940, Siruni published a 290-page book dedicated to Varoujan. He writes that as years pass the sense of the enormity of the calamity increases in our thoughts, that we will never be able to know the size of the calamity, the exact number of the people who died, and that is why we put the stress on the great individuals that was taken by darkness. “I do not know why each time I think about the massacre I hear the voice of Varoujan” – for him that greatness was embodied by the voice of the romantic poet, the voice of his friend.

The young Siruni had already witnessed Ottoman oppression. As a young student of Getronagan College of Istanbul, he was imprisoned in the last months of the Hamidian regime, in late 1907. His “crime” was being in touch with revolutionary groups, and what he did was to receive their pamphlets, read them first before distributing them further. When “hürriyet” came – as he calls the Young Turk coup d’état and the re-introduction of the constitution - he was freed to be celebrated a “hero” as political prisoner. He had initiated to establish a prison library, and after his release Istanbul journals joked that Siruni did not want to go out of prison because his library project was not over yet, and that he wanted to stay some additional months to finish another project, to establish a prison theatre group.

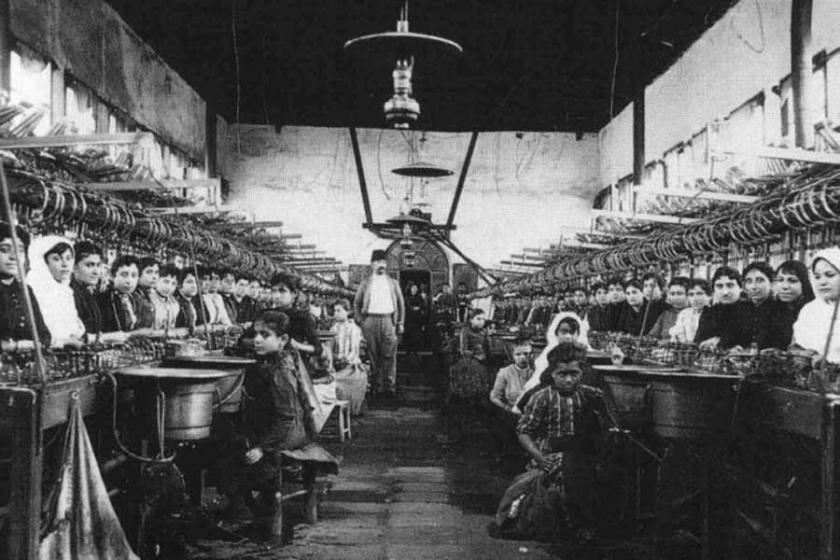

The end of the Hamidian autocracy and the re-introduction of the constitution inspired huge hope among the Armenian intelligentsia. Abdul Hamid II’s police-state was overthrown, the “red sultan” who had initiated the Armenian massacres of 1894-96 was gone. They had taken part in overthrowing in alliance with the Young Turks, and imagined the introduction of constitution will correct many of the ills of the Ottoman Empire. Once Hamidian censorship was removed, Istanbul became a centre of cultural and political activism. Books were printed and new newspapers were founded – like Azadamard the daily of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Tashnags) where he was the responsible-director. Siruni was also active through Esaian and Getronagan students association he had helped establish. In his memoires he writes that he organized cultural evenings with the participation of “Shant, Zohrab, Varoujan, Rouben Zartarian, Siamanto, Hovannes Setian.”

Another aspect of Siruni’s work that will accompany him throughout his life, was volunteer work to elevate the culture and education of his community. Already in 1912 and 1913 he organized summer courses for teachers from the provinces, with the participation of “Gomidas Vartabed, Taniel Varoujan, K. Khajag, Simon Zavarian” and others.

Later, in late 1913, he was imprisoned once again, this time by the Ittihadists, where he Jamal Pasha threatened him for articles published in Azadamard, where he was the responsible-director of publication.

At the end of the war, when the Ottoman Empire was defeated and the Ittihadist leaders escaped to Germany, Siruni came out of his hiding, and with few surviving intellectuals tried to re-establish a community that was mortally wounded. He was one of the initiators of a committee to commemorate victims of the massacres, on April 24, 1919, after which that day became the symbol of Armenian suffering, and a day of remembrance and demand for justice. It was on this occasion that the first monument to be dedicated to the Armenian victims, erected in 1919 at the Pangalti Armenian Cemetery, in today’s Gezi Park of Istanbul. The monument was destroyed after Kemalist forces entered the city in 1922.

The post-war relative freedom would not last long. Siruni sought refuge in Bucharest, Romania. There he became active both in Armenian community cultural and educational life – he was instrumental in setting up the Armenian Cultural Centre and numerous educational projects. He was also highly active in Romanian cultural life. It suffices to mention his friendship and long collaboration with the famous medievalist historian Nicolae Iorga, who served shortly as the prime minister of Romania in 1938. Later, Siruni would dedicate a book – 462 pages ! – to Iorga and his works, the historian, the journalist, the political activist, published in Beirut in 1972.

Another war exploded in 1939, reminding the first one. In 1940, Iron Guard fascistic group assassinated Iorga. Bucharest became often target of aerial bombing, forcing Siruni in the countryside. In 1944, after the Soviet Army occupied Romania, Siruni was arrested and exiled to Siberian gulag for ten years. The first none years will be difficult, as he did not manage to write in prison conditions. But the last year was like being in paradise: thanks to one of his former students, who had become the Catholicos of the Armenians, Vazgen I, had managed to bring him from Siberian captivity to Soviet Armenia. Afterwards, Vazgen I will invite Siruni to Armenia five times, to give lectures, organize conferences, and publish lengthy articles in journals of Soviet Armenia.

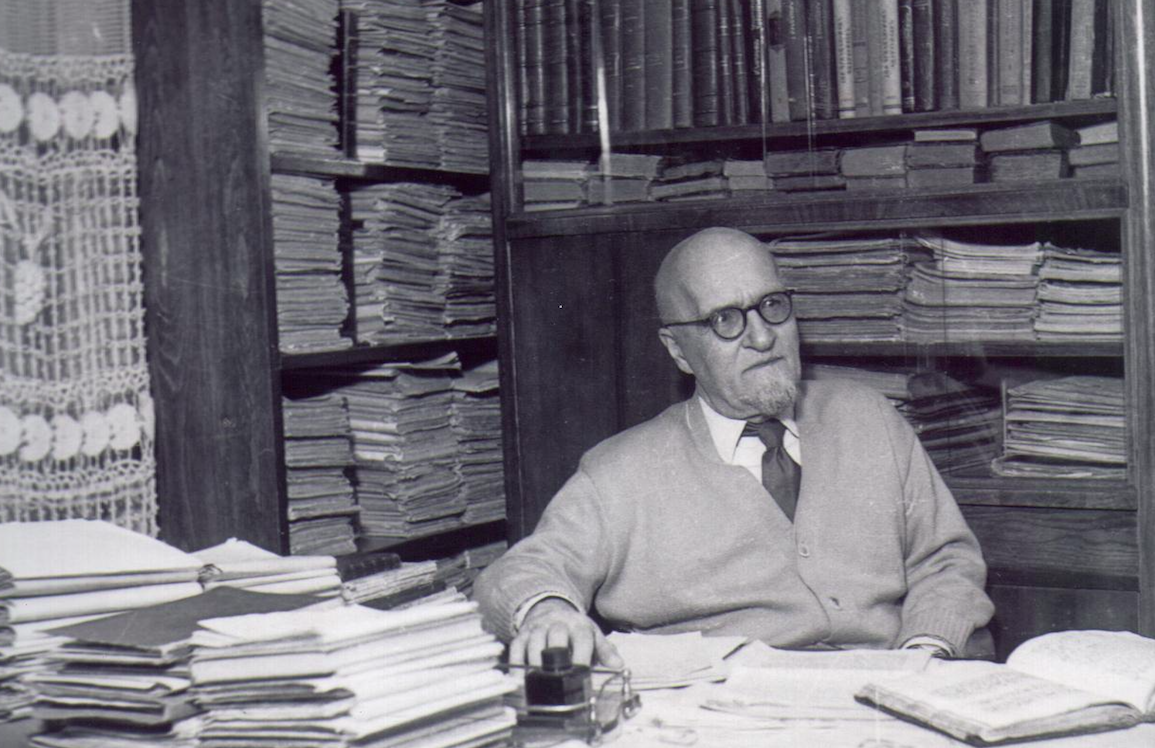

In his autobiographical notes – published in Yerevan in 2006 – Siruni writes referring to him and his generation “No one reached his summit. We were all left half way.” Indeed, it was a generation that did not fulfil itself. Some were to perish in Anatolia, others in the desert of Syria. Siruni himself escaped the worst in the hands of the Ittihadist for the first time, and the Stalinists a second time, yet even his work has remained half way. He recounts his love of books, and at four occasions he collected a large library only to be forced to leave again and loose his books. His autobiography itself seems unfinished: writing under Ceausescu he is silent about his time in the Soviet Gulag and Romanian “socialism”.

Siruni started his career as a poet, fiction writer, journalist and political activist. Yet, the great heritage that he left is in historic writing. His four-volume magnum opus, two thousand pages of Armenian history in Constantinople - Constantinople and Its Role (Bolise yev ir tere) ends by the end of the 19th century. He did not manage to finish his last volume on the history of his generation, what he had witnessed intimately, the destruction of his generation, of his family and friends. Under difficult circumstances, Siruni did the best he could. But he has left us a heritage to continue: to rethink the Armenian experience in the larger history of the Middle East, so that the Calamity the Armenians witnessed and its very important lessons now for 105 years, do not remain hidden nor ignored.