“The burden of the unspoken rests on our shoulders”

The film, which was completed during the pandemic period, was shown for the first time on a big screen on May 23 in Aynalıgeçit. Zelal Buldan, who stated that she had never been able to watch the documentary even with a friend before, watched in a hall with her mother, friends and other relatives of the disappeared. After the screening, there has been a discussion moderated by producer Ayşe Çetinbaş.

We talked to Zelal Buldan about the importance of the documentary for her, speaking/not speaking about the disappeared, and the difficulties of silence.

We saw that the film was very difficult and personal for you, you said this in the interview after the screening. It is actually a film about to face yourself, your life. How did you dare to take this journey and make this documentary?

As I mentioned in the documentary, I grew up under the influence of the unspoken, and the burden of this became heavier and heavier. I always knew I had to do something somewhere, I was looking for the right time and place. In my first film, I told the story of Hanım Tosun [one of the relatives of the disappeared]. Through that film, I was accepted to post graduate. Even this period, I still didn't feel that I was ready to tell my own story. In class, we were talking about the subjects we wanted to film and I started to focus on different stories. Every week I was submitting a different story to be filmed for my graduation project. Then one day, when I told my story in class, my professor asked me, “There is such a story and you are thinking of filming other people’s stories?”

You were actually maintaining the silence.

Yes, I did. I didn’t have the courage. That day I decided to shoot my own story. Of course, it was not enough for me to make this decision. I didn’t know what my mother would say about it. I thought about what I wanted to do, and then I called my mom and suggested that we say to each other through a video letter the things that we hadn't been able to say to each other until now. She agreed without thinking about it, actually. I think for her too, there was a lot to talk about and it was something she wanted to do. Then she came to me [in London where she attends her master's degree], I sat my mother down in a room where I was’nt there and asked her to think as if the camera was me and tell what she hadn't been able to tell me so far. I left the room and went to a place where I couldn't hear her, and then I did the same thing, this time in such a way that she went to a place where she couldn't hear what I was saying. I had a very hard time while watching my mother's video. As I listened to what my mother was saying, I realized how similar the things we had been talking about and communicating with our eyes for years were. Even though we couldn't hear each other, we spoke the same sentences. This is how the process developed. Later, even though I delivered these video letters to the school, I felt that this documentary was not over for me; I extended it, my brother was involved in the film, my mother and I did what I always wanted to do: We looked at the photos and videos together.

Haven't you do it before?

I hadn't watched videos about my father before making this documentary. That was one of the hardest parts for me. I even used a photo of my father at the beginning of the documentary, a photo that I normally wouldn't even dare to look at, a photo with a heavy burden. But I used that photo, I used the video of the funeral. I didn't want to hide these things; they are not things to hide, they are things that everyone knows. I couldn't run away any longer. I looked at those photographs and used them in the documentary, thinking that unless I face them, others cannot face them either.

While watching the film, I wondered the place where you shot the video letters. I understand it wasn't your home, is that right?

It was actually my house. My mother came to that house for the first time. I chose to do it in a place that meant nothing to her.

Communal mourning also identifies with space. Maybe it would not even be possible to record these video letters so openly at home.

Absolutely not. The place where the scenes where we talk to each other were filmmed, meant nothing to my mother. It was the same for me. It was a new house. I shot in the living room. It was a place I never used. It was an empty space that didn't mean anything to me, where not even a friend of mine came, that didn't hold any emotion. I know that if I had done it at our home, as you said, external factors would have been involved, it would have been even more difficult to do it in that space where we hadn't spoken for years.

On the one hand, you hosted your mother in that case. You invited your mother to the conversation. Physically, the shootings took place in your house. You invited her to open up about such a heavy grief that has been kept silent and unspoken since the day you were born. How does it feel that you invited her, that you took the lead?

I think I was the one who should have done it from the very beginning because I grew up with these unspoken things and I never thought that this would be a breaking point. I always learned about my father from the interviews my mother gave. For example, I have a memorysuch that: A journalist came to the house when I was little. I listened to that interview from a place where my mother couldn't see me. I learned a lot of details there. I also learned very late that my father was murdered. My mother was always telling us, “Your father is abroad”. She did this with the help of psychologists.

I have another memory: Again, when I was very young, we went to a visit. A little girl from the house I was visiting brought a book and in that book there were photographs of my father's tortured body. That was the first time I confronted my father in that state. Children don't do such things on purpose, but I learned so many details from such events. I remember another child saying something like, “Your father is not abroad, he is dead.” Then I'm just now starting to understand the impact of such events on me, newly, since the moment I made the documentary. I'm just now realizing what a heavy burden I was trying to cope with as a child. As I said, I think I was always the one who could break this, who could take the first step.

By the way, when I talked to the relatives of the disappeared, I realized that this is not something unique to me. These issues are usually not talked about much at home. Most probably to protect us, the children, but the burden of these unspoken things starts to fall on our shoulders, so something needs to be done.

When I watched the documentary, I couldn't stop thinking about you and looking at Zelal there. In similar situations of severe loss, we can neglect to think about those left behind. That's why I saw the painful way of bringing you, your grief, your mourning to a place. You were born on the day your father was killed. Did you ever celebrate a birthday? What are your memories of your childhood in this regard?

Of course we celebrated, but it was like this: My friends surprised me. Not on the same day, but the day before or after. For me, June 3rd is waking up in the morning, going to the cemetery and coming back and not leaving the house that day. I couldn't find the energy to go out. Actually, the breaking point for that was the documentary. We released the documentary for the first time four years ago. Last year on my birthday I made myself a birthday cake, with my own hands. On that day, June 3, I blew my own cake, because on the other hand, there is such a reality, there is the reality of my birth. I can say it was a process of making peace with myself, with my birth. My birthday is coming up soon, I will be 30 years old. It is one of my most important birthdays because my father was 30 when he was killed. In fact, this year I realized how early my father was taken away from life. I am 30 years old and I feel that I have lived very little. For this reason, June 3 this year has a special significance for me.

In the video letters in the movie, you and your mother talk about things you couldn't talk about for years without looking at each other. After the documentary came out, were you able to break that distance, that difficulty and look at each other and talk?

There's a scene in the documentary where we talk face to face: The last scene. My aim was to say what we had to say to each other in separate rooms and to do it together at the end. I shot the last scene in the family home. There is a photo of my father in the background. Actually, when I asked my mother a question there, she couldn't say anything from the heart. She could say something more about the struggle. At the end I asked her again, I told her I wanted to hear something more from the heart. She said, “But I can't talk to you about such things” and that was the end of the documentary.

Of course something changed because even though we didn't talk about it face to face, even though we talked about it in separate rooms, I think these videos brought us closer to each other. Even if there are still things we can't say, our understanding with the eyes has gone to a higher level.

I think something changed after the screening of the film too. I watched it with other people for the first time. The day I released the documentary, we all had retreated to our own rooms and watched it. I hadn't even watched the movie with any of my friends, and I hadn't watched it afterwards because I had watched it too much during the editing process and it was difficult. I watched it for the first time at the events of the 1000th week of the Saturday Mothers, with a hall full of people, with my family, with my friends, with the families of the disappeared, with people I didn't know. My mom didn't want to come at first. “I didn't want to come because it wouldn't be good for you,” she said at first. But I know it was because she wouldn't feel well either. When she came, I asked her not to sit in the front row, I knew I couldn't do the interview. She didn't sit in the front row, but in the second row. My brother couldn't come, he didn't feel ready. I didn't want to make eye contact with my mother after the screening, but it was more comfortable afterwards.

Maybe something broke after the display...

I think so too. I felt a little closer to my mother.

In the film, you turned your face to the place that was closest to you, the quietest and hardest place, your family. This was perhaps the most challenging way to learn about your father. Can you tell us about that?

Even though the title of the film is 'about my father', it was also a film with my mother. I could have learned a lot more about my father by talking to strangers. My uncles, aunts or my father's friends would have given me a lot of information, but it never crossed my mind to talk to them. I wanted to learn from my mom, not only about my dad, but about her feelings towards me…

As I got closer to the Saturday Mothers and other relatives of the disappeared, as I started to share things with them, I started to heal. I always say this.

Is there anything you want to add?

I gave an interview after the film and the interview was published with the title 'I thank my father the most' even though that sentence wasn't actually said that way. I actually thank my mother the most. I don't know if I should say that, I don't want to put anyone in a difficult situation. But I want to thank my mom.

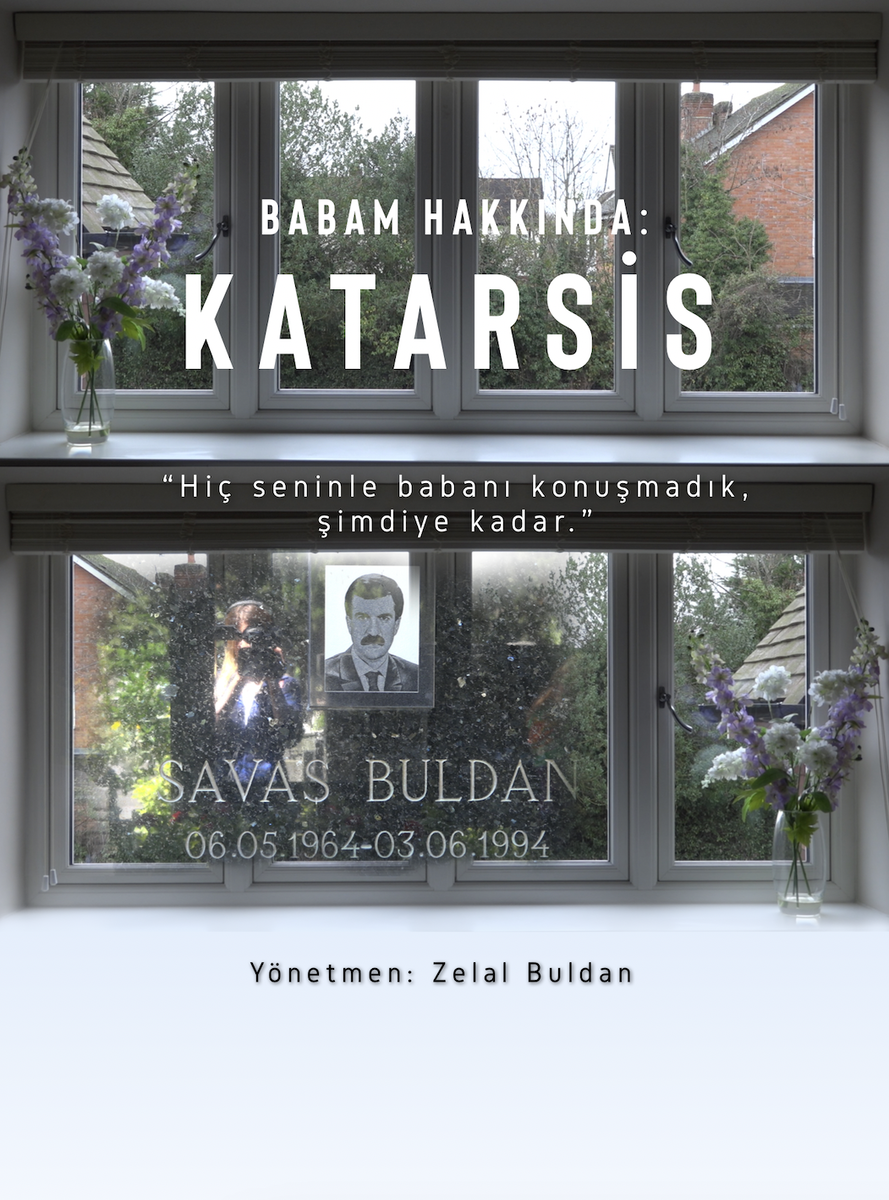

About My Father: Catharsis

Zelal Buldan graduated from Bahçeşehir University, Department of Cinema and Television. She completed her master's degree in Documentary by Practice at Royal Holloway, University of London. She continues to work as a director, screenwriter and script consultant.

The promotional text of the film reads as follows:

"Between birth and death, on a June day... Zelal, born on the day her father Savaş was killed, grows up under the influence of the unspoken. Since talking is a difficult and painful process, it has been postponed for years. The word 'father' is never mentioned in this house. Zelal, who has been talking to her mother through her eyes until now, decides to make a documentary. Through this documentary, mother and daughter make a real connection after many years and start talking about the Savaş."

The movie can be watched here.