German Avagyan is a photographer who participated in joint Armenia-Turkey exhibitions before it was a trend and has always used his camera for documenting the difficult issues that became a wound for the society. In this regard, interviewing him is precious, not only in terms of photography but also in terms of understanding how photography can really change people's lives. We introduce this artist concerned with many issues like poverty, disability and war to our readers.

Can you briefly talk about yourself? Where are you from? How did you start taking photographs?

I was born in the USSR, in the family of a Soviet Army officer in 1962. Before I reached the age of majority, we had to move many times depending on which military base my father was serving in. When I was born, my father was serving in Georgia. Perhaps that is why my love towards Georgia was in me before I came into this world. I cannot explain this any other way

My father and my grandfather were from Kerchenj village, Shemakha region, Azerbaijan. Before 1988 there were about 40 Armenian villages in that region. Our ancestors moved there from Khoy, province of Iran, in 1826. My father found this date written on the stone of the oldest grave in the village cemetery.

After begging my father over and over for a camera, he finally got me one in 1975, thinking it was a childish whim. The ordinary Soviet camera Viliya turned my life around. From that moment on I never stopped taking photos.

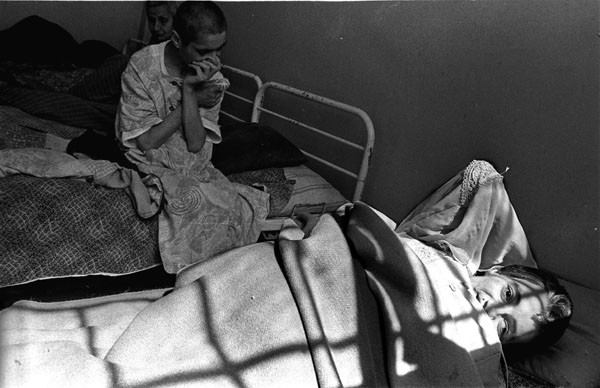

You have always been concerned with social and political issues such as poverty and disability, landmines and elections in your photography. Your early work has many projects about the poor, the blind and the mentally disabled. Tell us a little about the importance of exposing such issues through your photography.

I started working on long-term projects later in my career, around 1998. Back in those days we did not even know on such approaches to photography. It was a coincidence. The Armenian Social Investment Fund, which financed repair works at the Vardenis mental hospital, asked me to take photos there. They needed the photos for their annual report, and my friend Edik Bagdasaryan, who worked as a Press Secretary for the Fund, asked me to do the photos. When I got to the hospital I was horrified by the condition of the patients. There was no light or water at the hospital; there was a deadly smell. Having forgotten what I came for, I started taking photos of the patients and the surroundings. Then a newspaper article came out…and then another. The articles were accompanied by photos. The Government put the issue of the condition of the country’s mental hospitals on the agenda of an urgent meeting. And the ice was broken. The position of the patients started improving. I continued taking photos in Vardenis. I was taking photos there until 2007, when the director was changed... but this is another story.

Working on the same project year after year is hard. It usually doesn't bring money; on the opposite, you just have to spend money on your project

In 2002, when a Fund for Documentary Photography (San Francisco, USA) honoured my project with an award and a photo exhibition was held in San Francisco, to my surprise, the local Armenian community ignored (I would say boycotted ) it. As it was explained later, it was considered damaging and inconsiderate to present the problems ofArmenia’s mental hospitals in the USA. However, for me this is not a problem of a single country. This problem exists all over the world. And in Armenia, unlike many countries, thanks to the photo project, this problem started to be taken care of.

Ideas for my projects are inspired by life itself. When I took photos at the School for the Blind in Yerevan, I found out that some children had lost their vision as a result of explosions of landmines or unexploded ordnances left behind after the war in Artsakh. The war was over, but children were getting maimed and killed due to those deadly devices. I started photographing the children who became disabled because of a war even though the war had ended. But you know, funds were required for making trips to the Armenia border villages where the mines were. I sent a proposal for my project and some photos I had already taken to a photo contest organized by the Hasselblad Foundation in Sweden. To my surprise I received a scholarship. In 2002, two years after I had started my Project «Lethal Toys», I received the financial support which allowed me to make trips all over Artsakh and Armenia’s border villages. I took photos of over 50 children. Unfortunately I saw many children's graves, which their grieving parents showed me. Their children were killed by landmines and unexploded ordnances they had found after the war.

Some years later, in 2004, a TV company made a film featuring the project. The film was broadcast in Artsakh and Yerevan. Unfortunately, in those days this TV company did not broadcast all over Armenia, and residents of border villages could not see the film. However, fortunately if a project is important, there are always people and organizations ready to help. UNICEF made several hundred DVD copies of the film and sent them to the Armenian border villages. Having watched the DVDs children saw the danger that the “lethal toys” posed for them. Therefore my photo project reached its adressee.

There is one thing I can say for sure. Incidentally, since 2007 when the film about my photo project was widely broadcast in Armenia, not a single child has been killed or injured by landmines. Not even one case! The exception is Gyumri, where two children were killed at the Russian training ground. The children had found a charge for a grenade launcher. Apparently they hit the fuse with a stone. Gyumri was the only city where the television station refused to show the film, reasoning that Artsakh was far away and there was no war in Gyumri. I could not convince anyone that the Russian training ground posed a danger.

Lives, children's lives saved thanks to this project - this is my best award in Photography.

Don't the saved lives prove the importance of photo projects?

I have worked on three projects about the cosequences of the Armenian-Azeri war, i.e. its aftermath. We spoke about the first one. The second is devoted to children who were born after their fathers were killed in the war. These photos reflect on death and life: a symbol of death - an old photo of the father, who perished at the front, held by the hands of his child who is a symbol of life - the child and the hero are the subject of my project. In addition to the photos, brief biographical information is provided: not only the last names are the same, but often also the first names of the fathers and their children; date of a child’s birth and date of a father’s death... What lies behind these images and figures are people’s fates, and the country’s fate. There is a hidden factor - a widowed young mother who gave birth to her child and brought him or her up by herself. Therefore, not only has she kept the memory of her killed husband, but she has also retained her husband himself. Because the birth of a child whose father is dead is a kind of incarnation/ reincarnation of the person who has left this world. It is confirmed by the striking likeness between fathers and sons, similarity of the names given to children by their mothers...

The photos were taken in Nagorno-Karabakh and in Armenia from 2009 to 2012. The images depict children who have never seen their killed fathers. The only memory of their fathers are the photographs they keep. These photos are an integral part of every home, every family, that has lost its nearest and dearest in the war

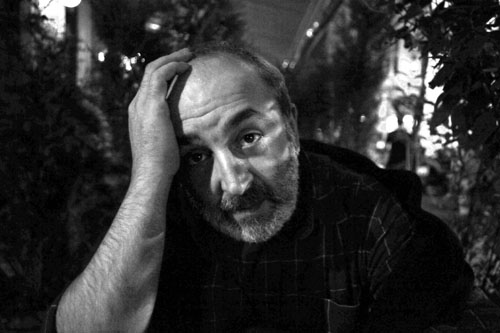

You were one of the participant photographers in the “MERHABAREV” book project that brought photographers from Turkey and Armenia together in the late 2000's. There were hardly any such projects to create a peaceful dialogue between the two countries at the time. Tell us about your experience and involvement in this project.

The project was started just by chance. My friend, Ruben Mangasaryan, (he died in 2009, God rest his soul) asked me to replace him at a meeting of Armenian and Turkish representatives, held in Yerevan. On that day Ruben was participating in some seminar in Russia. That was in 2006. I was boring at that meeting. All the participants from Armenia were talking about the impossibility of collaboration, because there were no diplomatic relations between our countries. Musicians, historians, journalists ... Everybody was talking about the impossibility of establishing cultural contacts or implementing joint projects. Having nothing else to do, I started to look through the booklet they provided. Having read the participants' list, I found out that it included a Turkish photographer: Özcan Yurdalan. So, I asked for the floor, and told something like the following:

“If you consider that collaboration and joint projects are impossible, I would like to talk during coffee break, to the photographer who is among our meeting participants.” Photographers will always find a common language. During the break we agreed that we should think over the steps we can undertake together. In the evening we came, already prepared, to a banquet in a restaurant. When we were going for a smoke, we started to discuss the prospect of our collaboration. All of a sudden, a lady came up to us and said, “We will finance whatever you think”. Later I knew that it was the Director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation's Office in Istanbul.

Ruben Mangasaryan got to the restaurant just in time for our meeting. And the work began. Later, in Istanbul, Özcan introduced me to Hrant Dink, who was very happy about our photo project and wanted support it in every way.

You have to understand that that was the first cultural contact between the two countries over the last 90 years . In the few years since then, the idea of cultural projects between the two countries has become a stable source of grants for many Armenian NGOs, therefore I was pushed aside from the project. However, it’s good to know that I have trusted friend in Istanbul with whom we maintain true friendship and not just collaboration for the sake of grants.

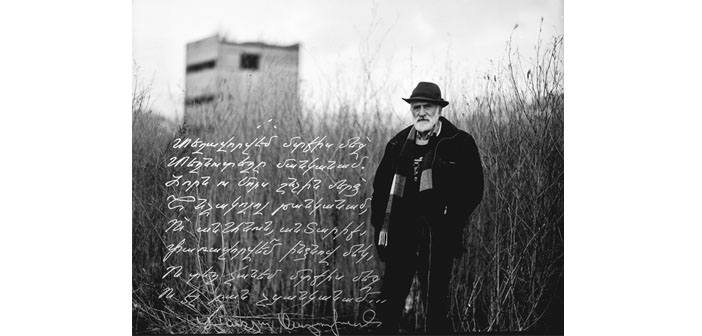

The book Visual Poetry is very different from your earlier work. How did the book come about? Were you aware at the time that you were going to collect such a special body of work about the literary personalities of Armenia?

The seed of this photo project was planted many years ago, in 1989, when I was hired under contract by the “Garun” literary magazine. Though I had no permanent salary, I found great reward in the constant flow of communication with young poets and writers. That year the national movement in Armenia was at its peak. New names appeared in Armenian literature, unsullied, for they had had no collaboration with the former communist regime.

The shortage of money was compensated by gatherings in bars where young poets read their poems for the first time. I was lucky to find myself in a 'foreign' language environment. I was learning Armenian in good company - listening to poems read by the authors themselves. Alcohol only helped to accelerate the learning process.

To impart a sense of what “Garun” magazine of those days was, it suffices to say that I knew families who ordered two subscriptions so as not to argue about whose turn it was to read each new issue. Circulation of the magazine reached six-digit numbers. In other words, every twentieth inhabitant of such a small country as Armenia was familiar with the content and authors' names that appeared in the magazine.

It was then that I met Armen Davtyan, Tigran Paskevichyan, Vahagn Atabekyan, Vahram Martirosian, Khachik Manukyan and others. I was young and did not doubt that I was a genius in photography. We are all geniuses when we are young. Many years later I realized that I was just a minion of fortune, having turned up in the company of such poets and writers by chance, yet was not ready to implement it into a serious project. My belief at that time was that photography should be in a dependent position to poetry. Photography assumed the function of illustrations to poems. Somehow, this was not enough for me. I wanted to present photography and poetry as equals.

It took 25 years for my idea to completely take shape. Only when I read Joseph Brodsky's essay, “To Please a Shadow,” did I find the solution to my dilemma: “Strange things they are, faces of poets. In theory, authors' looks should be of no consequence to the readers: reading is not a narcissistic activity, neither is writing, yet the moment one likes a sufficient amount of a poet's verse one starts to wonder about the appearance of the writer. This presumably, has to do with one's suspicion that to like a work of art is to recognize the truth, or the degree of it, that art expresses. Insecure by nature, we want to see the artist, whom we identify with his work, so that the next time around we might know what truth looks like in reality.” These words are the key to my Visual Poetry photo project.

It is interesting how you have combined the poems with the portraits. Were all the poems written especially for the portraits? Do you have any regrets about this series of portraits (maybe some of the poets have died since you photographed them so there is no poem)?

After shooting with a Large-format camera and printing the black and white photos, I invited poets to my office, gave them the photographs and asked them to write on their portraits ANY poem they wanted that in their view, would be consistent with their portraits. I did not interfere in the process. I went out of the room when they wrote. The poems were not written especially with the book in mind. But, for example, long before this project was implemented, Tigran Paskevichyan had mentioned me twice in his poems. And one poem was totally dedicated to the portrait I had made of him many years ago. But, once again, that was written long before the project. Metaphorically speaking, I ended up paying my debt to the poets through my project. To my regret, I did not manage to photograph everyone I wanted to. For example, Vahagn Atabekyan has been out of Armenia for many years already, so I could not photograph him.

The book exists due to the fact that we still have connoisseurs of photography and poetry in Armenia. I would have never managed to cover the cost of the book publishing by myself. I made an exhibition, which a month later was attended by Ashot Gasparyan, a book publisher. He told me that he had never seen such a synthesis of photography and poetry, even though he had been dealing with book publishing for more than 40 years. He published the book at his own expense, for which I am truely grateful to him.

To my great regret, Hrach Sarukhan passed away after the book was published. I only had time to give him the book. It was our last meeting.

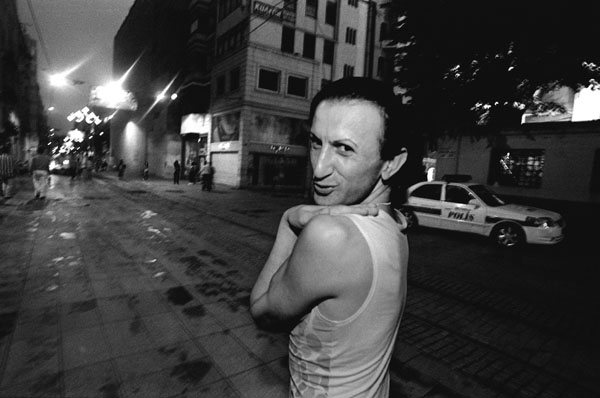

You live in Armenia but you have also spent many years of your life in Georgia and the United States. Tell us a little about your feelings about and experience in being a photographer in these different countries. How easy or hard, how challenging has your life as a photographer been in these different places?

When I lived in Georgia, I probably experienced the happiest moments in my career. Armenia is close by, and I never missed any interesting event. I photographed in Armenia and in Georgia. The customs and traditions of Georgia were not alien to me. There were many opportunities to photograph people of different nationalities, religions and cultures. As a result, an exhibition "Faces of Tbilisi" was held in Istanbul (IFSAK) in 2010. Tbilisi and Istanbul have something in common. Working in Istanbul for me was easy as well. Working in the USA was more difficult. I took many years of plunging into another culture before a photo project appeared.

You have also published a book called “Armenia: Stolen Voices”. Tell us about this book.

This is an Internet edition. Anyone can order this book. I posted it on the Internet edition site. In 2008 it cost about USD 27. The price seemed too high at that time… But now it costs about USD 50. Apparently, everything is getting more expensive in the US as well.

“Armenia:Stolen Voices” is a kind of diary, where the events of February/March 2008, which took place in Yerevan, are described. The authorities killed 10 peaceful demonstrators. Until today nobody guilty of the death of those young people has been arrested or unmasked. No criminal charges have been laid. This is an open wound that is not healing.

As someone who has dedicated his photographic life to uncover the social and political realities of the country, what are your impressions about the new generation of photographers? In this modern age, everyone has a camera and they photograph anything they see with a compulsive obsession. What do you think about this? With all your years of experience, do you dream about establishing a school for young photographers?

School? What for? To teach how to photograph? There are user manuals, which are sold with cameras. And if you study the manual when you buy a camera, you will take quality pictures. But they do not read…They just put the camera on automatic mode. That is enough for them

More important for me is a need to teach the ability to feel compassion and sympathy for others. But a photographer alone cannot do that. That must be cultivated in early childhood, within a family, at school. This is the mission of Art in any given society.

Anything you want to add?

I have some completed projects, which, unfortunately are of no interest to anybody in Armenia. There is for example, a project about women who have been waiting for their husbands and sons to come home from the war, more than 20 years after the war has ended. The project’s name is “Woman Waits”. It is about those who went missing.

There is another project about a self-taught artist who started painting after he found himself in a nursing home.

And another one about children who became disabled during the war. Today they are already grown-up people who get childhood disability benefits which are much lower than benefits received by war veterans.

I am not much of a tourist. If I go somewhere, I go there to work: exhibitions, shooting, etc.

Being a tourist for me is a waste of time and money of which, funny enough, we never have enough for photography projects anyways.

When I photograph, I do not think about “realization”. That is why my projects wait many years for their time to come. Thus, “Faces of Tbilisi”, which I showed in Istanbul in 2010, took 6.5 years before I could show it in Tbilisi. At the exhibition opening I was very pleased to see Vagif Akberov, the former Mufti of Georgian Muslims, who welcomed the the guests in Armenian. A hailstorm of negative reaction against this great man was raised in Azerbaijan. But I am sure his spirit is strong. And his aspiration for peace will win! My hope is that my photo projects bring people closer. This, I believe, is the foundation of humanistic photography.