Boxing, dance, and Romani culture: An extraordinary film experience in Leipzig

I’m slowly getting used to Leipzig, where I arrived about ten months ago. Initially, I stumbled a bit, felt foreign, and experienced loneliness. After all, this city is neither Berlin, nor Cologne, nor Hamburg. Apart from a friend who also decided to pursue a master’s degree here, I knew no one in this relatively small city with a population of 700,000. It may seem like I’m complaining, but I must say that my reasons for wanting to ‘escape’ from Istanbul don’t fully align with wanting to stumble; rather, it was my need to feel foreign and alone in a place I live.

As I mentioned, I’m gradually adapting to life in Leipzig. Like every diaspora, there is a communication network among Turks living here. I became aware of the Kültür Kollektiv Leipzig (KÜKO), a platform established by people from Turkey here. KÜKO organizes various cultural and artistic events, which help me in my adjustment to the city and allow me to explore cultural and artistic content from my home country in a completely new setting.

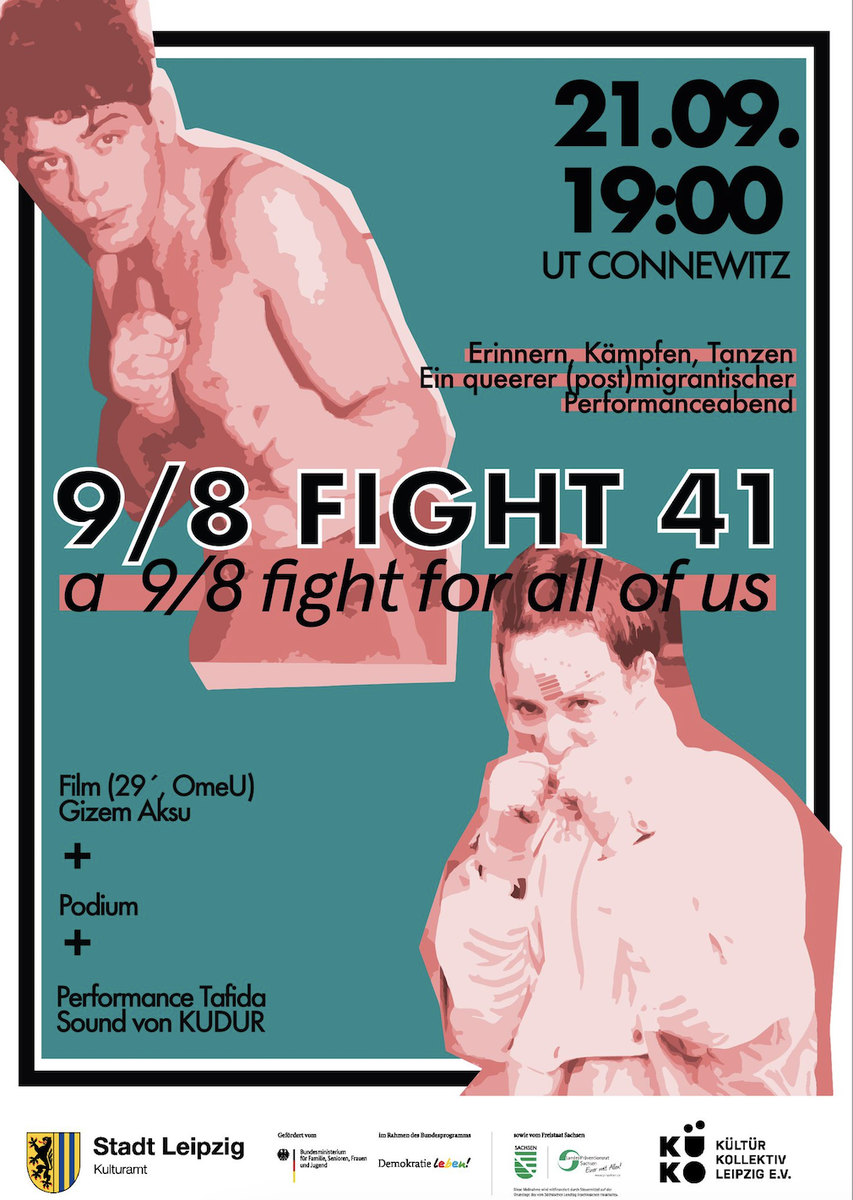

For some time now, KÜKO has been screening films that focus on LGBT+ individuals from Turkey. On the evening of September 21, Saturday, they held another screening at UT Connewitz, the city’s oldest cinema, located in one of Leipzig’s multicultural neighborhoods. About 100 people gathered in this historic venue to watch ‘9/8Fight41,’ directed by dancer Gizem Aksu, who recently migrated to Berlin. After the hosts, Aslı Koruyucu and Mavi Kotan, provided information about the film and the event to follow, we began watching the film, which connected the story of a boxer I had never heard of before to urban transformation in Istanbul.

Johann Trollmann, aka ‘Rukeli’

The boxer I had never heard of before was Johann Trollmann—often referred to in the text as ‘Rukeli’. This light heavyweight boxer became a popular figure across the country in the late 1920s, fighting with a unique ‘dance’ style he had created. On June 9, 1933, he fought for the German light heavyweight title. Despite being ahead on points against his opponent Adolf Witt, the match was declared a ‘no contest’. Following the audience's outrage, Nazi officials were forced to declare Rukeli the winner, but six days later, his title was stripped away.

A new fight was scheduled for July 21 against his opponent Gustav Eder, and Rukeli was threatened that he would have to change his ‘dance’ style or lose his license. On the day of the match, Rukeli dyed his hair blonde and whitened his face with flour to give himself an ‘Aryan’ appearance. Here, I need to highlight the most crucial detail about both Rukeli and the film: Rukeli was a Romani, and for this reason, he had identified his boxing style with dance, which led to him being "punished" by Nazi Germany.

A new fight was scheduled for July 21 against his opponent Gustav Eder, and Rukeli was threatened that he would have to change his ‘dance’ style or lose his license. On the day of the match, Rukeli dyed his hair blonde and whitened his face with flour to give himself an ‘Aryan’ appearance. Here, I need to highlight the most crucial detail about both Rukeli and the film: Rukeli was a Romani, and for this reason, he had identified his boxing style with dance, which led to him being "punished" by Nazi Germany.

The persecution of Sinti and Roma increased significantly in Germany in the following years. Like others, Rukeli was subjected to forced sterilization before being sent to concentration camps. In June 1942, he was arrested and sent to the Neuengamme concentration camp. He tried to keep a low profile, but the camp commander had been a boxing official before the war and recognized him. He used Rukeli as a trainer for his soldiers at night, but later the prisoners’ committee decided to intervene due to Rukeli’s deteriorating health. A fake death was arranged for him, and he was transferred to the adjacent Wittenberge camp under a false identity. Rukeli was quickly recognized there as well.

The prisoners organized a fight between Rukeli and Emil Cornelius, a former convict and Kapo who harbored a grudge against him. Although Rukeli won the fight, Cornelius sought revenge for his humiliation, forcing Rukeli to work all day until he collapsed, then attacking him and killing him with a shovel. Rukeli paid the price for being Roma with his life at the age of 36. After being abducted from the Neuengamme concentration camp, he was assigned the prisoner number 9841, which also appears in the film's title.

From Dresden to Sulukule

But how was the film queer-themed? How did it relate to urban transformations in Istanbul? The film, which features three other dancers alongside Gizem Aksu, begins in a boxing ring in Dresden. Set to the Roma-influenced song ‘Şukar Şukar’ performed by Kardeş Türküler, Aksu dances in the boxing ring inspired by Rukeli, narrating his story. We then transition to Berlin, where we watch Aksu perform a dance in a snow-covered park while listening to how dance has influenced her own migration story. Aksu notes that the rhythm of the dance known as ‘Roman havası’ is in 9/8, which corresponds to the numbers 9 and 8 in Rukeli’s prisoner number, explaining her choice for the film's title.

Next, we move to Istanbul, to Sulukule. After a shot of Rukeli’s large photograph wandering the streets of the city, we see dancer Gizem Nalbant recounting the urban transformations in Istanbul's Roma neighborhoods. Nalbant shares her experiences of witnessing these changes and describes how they have ‘resisted’ this destruction through dance.

Next, we move to Istanbul, to Sulukule. After a shot of Rukeli’s large photograph wandering the streets of the city, we see dancer Gizem Nalbant recounting the urban transformations in Istanbul's Roma neighborhoods. Nalbant shares her experiences of witnessing these changes and describes how they have ‘resisted’ this destruction through dance.

In a segment where Sema Semih discusses their journey of discovering their trans identity, expresses that while they thought they were walking ‘normally’, they were actually ‘limping’. Sema Semih also, like Aksu and Nalbant, clings to dance with a protest motivation.

Banu Açıkdeniz, a dancer I know from Boğaziçi University’s Folklore Club, reminds us of the violence and oppression faced by women in Turkey, turning her dance into an act of rebellion against anti-woman and anti-LGBT+ policies.

The film illustrates how dance serves as a tool of resistance, affirming Graham’s quote I mentioned at the beginning. I regret not having watched it sooner, but I’m glad I finally did. The film will be available to watch on Mubi Turkey until the end of the year, and it’s a must-see.

From the Film to the Party

After the film, there was a discussion moderated by Aslı Koruyucu. The film's director, Gizem Aksu, along with Tafida Galagel, an oriental dancer living in Leipzig, and Ilgaz Yalçınoğlu, one of the co-founders of the Berlin-based KUDUR organization known for its DJ performances, spoke about migration, dance, and LGBTQ+ issues. Following this, Tafida took the stage with a special performance prepared for that night. After Tafida, KUDUR DJs Ilgaz Yalçınoğlu and Ari Kozanoğlu invited the attendees to ‘let loose’ with their set while reminding everyone that dance is one of the most powerful tools of rebellion.

KÜKO’s next film will be ‘Mavi Kimlik’ (Blue ID), directed by Burcu Melekoğlu and Vuslat Karan. The film will be screened at Leipzig University on October 24, at Luru Kino Spinnerei on October 25, and at Cine Ding on October 26.