6 Azerbaijani and 4 Armenian people came together in Eskişehir and talked about peace and common life without a third party. Varduhi Balyan witnessed this important and touching meeting, spoke to participants and told about her own story. In the hope of more meetings like this...

While

the number of clashes are increasing day by day all around the world,

the people who understand that no one can be a winner in a clash or

war have been trying to relieve the tension. Unsteady political

borders that emerged after the formation of national states affect

people's lives directly and tear them apart from their lives,

cultures, neighbors and relatives. This situation keeps repeating

itself like a vicious circle and continues to separate the ones who

have the same backgrounds and stories, just because they are on the

opposite sides of the borders. However, there are meetings as well.

Growing apart because of Karabakh conflict, Azerbaijani and Armenian

people came together in Eskişehir in Turkey, talked about the

current political atmosphere in both countries and clashes and shared

their personal stories.

Our past is common

I am a member of a family which had been directly affected by Karabakh war and forced to leave their house and village. The war and the following conflict brought only suffering to the both sides. And as always, there was no winner of this war and no good came from this conflict. When we came together with people of the same age and mind with us, with whom we cannot see and talk because they are on the other side of the border and listen to their stories, we understand that we are not alone and begin feel hopeful.

After 3 days we spent together, talking and eating, Aynur (this is not her real name) from Azerbaijan hugged me and said that her grandmother is Armenian; at that moment, I remembered Laura from my grandmother's village. Laura, who, even after 24 years, hasn't still confided in me that she is Azerbaijani. I wonder how many times she wanted to do this but got scared because of the hatred imposed by the state.

The story of Azerbaijani İdgar, who made this project called “Pigoens fly above Caucasus” happen, is no different. İdgar (he also doesn't want to reveal his identity due to safety concerns) has also a house on the other side of the border; there are the stories told by his family, the nationalism that he managed to do away with and the peace that he wants to build.

Saying that his family is from Zangilan, Karabakh, İdgar starts to tell the story of his family: “In 1993, my family had to leave Karabakh, because their home was occupied. Crossing the Aras river, they headed to Iran and then went to Azerbaijan. Zangilan is on the southernmost part of Karabakh; there are Cabrayil and Kubatlı to the north. Since there were Armenian soldiers in Kubatlı, they couldn't have gone there and had to go to Baku through Iran. That year, they settled in a school building in Baku with other families from Zangilan. My family still lives there. The first floor of that building is still being used as a school and people are living on the other floors. 65 families are still living there. I also spent the majority of my life there. Whenever my family wanted to renovate the house, officers from the municipality came and said: “Don't do this. Don't harm the building. You will return anyway. Our state will take Karabakh back and you will return to their homes.” We always felt like we are about to leave. I mean, the state was successful in imposing that feeling. The state made its presence felt.”

“The war was among the soldiers”

From what İdgar says, we also understand that the people didn't want war and don't consider each other as enemies: “My whole family, my uncles went to the war. My father also wanted to go, but my uncles didn't let him, because they were already in the war. They thought if something happens to them, my father would look after their wives. All of our neighbors in the building went to war. However, something else had happened. My father told me that when they first settled in the building, state officials came and tried to recruit new soldiers. All men in the building went to the toilets in the backyard for hiding. I mean, men always talk about how they went to war, but these people are the ones who didn't want to go to war. Even after the war erupted in Karabakh, those people weren't aware what is happening. My aunt told that she went to offer 'xonça' (a tray full of food) to the Armenian soldiers for Newroz, when there were clashes in the neighboring regions. And she told this as if it is something usual. She thought that those soldiers are not against her and the war is among the soldiers.”

“My father's 'kirve' was Armenian”

I know from my family that people who are separated because of the war look for their friends afterwards. People in the neighboring country have similar experiences: “In Karabakh, my father's 'kirve' was Armenian. For us, kirve is an important person. This means that they valued him. His name was Antranik. Now, my father has no contact with Antranik. It makes me sad. Once, we searched high and low in the website called 'Odnoklassniki' for Antranik, because almost everyone in our region has an account, even the elders. He created a fake account for finding Antranik, but he couldn't. Maybe he is already dead. He was old. However, we look for him once in a while.”

While I am talking to İdgar, I am recalling the stories that my grandmother told. Spending her whole life in Barum village in Şamkir and then forced to leave in 1988 only with her official papers and essential belongings, my grandmother told that my grandfather's Azerbaijani friends were coming to their home until the very last day: “They were saying that the situation is bad, but it seemed like things were happening away from us. We were still coming together with our family friends and your grandfather was still going to work. It seemed like that tension was happening elsewhere. Until one day, an Azerbaijani friend from a village near ours said: 'The situation is really bad. I am afraid that they may kill you. You have to leave with your family.'”

My grandmother always talks about these with longing. She always talks about their Azerbaijani friends and feels happy when she finds out where they are living now. She tries to contact to them.

“I was a genocide denialist”

İdgar talks about how he got rid of his hatred against Armenians and his nationalism: “From the stories I heard in the camp, I remembered the ones about the war and Armenians. I was thinking that Armenians made our lives miserable and I wouldn't come near to any Armenian. After I came to Turkey, I started to read more. I read about the state and then the war started to seem strange to me. Before I came to Turkey, I was nationalist. Once I came here, I slowly got rid of it. When I was in Istanbul, I saw a poster that reads 'Hrant Dink was murdered here.' I was shocked. I started to question the reasons of that murder. Dink was a person who wanted peace, why was he murdered?

I was a genocide denialist, because it is what's written in our textbooks. Now, I think that 1915 is the most wicked incident that happened in Turkish history. More than 1 million people were deported and killed. I learned these things by researching. I started to read different books. Similarly, I don't understand people who defend Karabakh war, the demise of people.”

“It is not a matter of ownership, it is an emotional bond”

Believing that there will be peace in Karabakh one day, İdgar thinks that the solution is in common life: “I believe that we should live together like we used to. Once upon a time, Armenian, Azerbaijani and Kurdish people living in the region were coming together in the evenings and sharing laughs and mulberry oghi (vodka); this can happen again. We all know that this is not yet possible, but we can achieve this. We will achieve this. I don't say that the people living there now have to leave, but I want my family to return there, because they miss those places very much and they built their house with their own fair hands. It is not a matter of ownership, it is an emotional bond. For instance, it also holds for the grandchildren of the genocide survivors. Armenians had houses all over this land. There were Armenian neighborhoods even in Armenia.

I know a taxi driver from Baku. He drove someone to Tbilisi to an Armenian house. The Armenian living in Tbilisi wanted a stone from Çapayev street in Baku. Since it was late when they arrived, the Armenian asked the drive to spend the night there. When they gave him the stone, the Armenian kissed the stone and put it on his eyes. This is a bond, not a feeling of ownership. For genocide survivors, a house in Istanbul is not just a house; it is an emotional place, a struggle, it is about the joy of reading a book there.”

“Pigeon flies above Caucasus”

Since the border is closed, Azerbaijani and Armenian people come together in a third country and take part in tripartite projects. However, “Pigeon flies above Caucasus” project is organized only for dialog between two sides. İdgar tells about the project as the following: “Being alone together is what is important. When people are alone, resolution is easier, even in terms of identity issues. I wanted Azerbaijani and Armenian people to talk to each other without feeling obliged to explain things to third parties. I did this because it is a need for me. The governments of Azerbaijan and Armenia maintain their existence through this war. I would be very glad if I could be one of the people who manage to bring Azerbaijani and Armenian people together, even after 40 years. I designed this project for preventing my grandchildren and the ones who I consider as my grandchildren from hating Armenians in the future.”

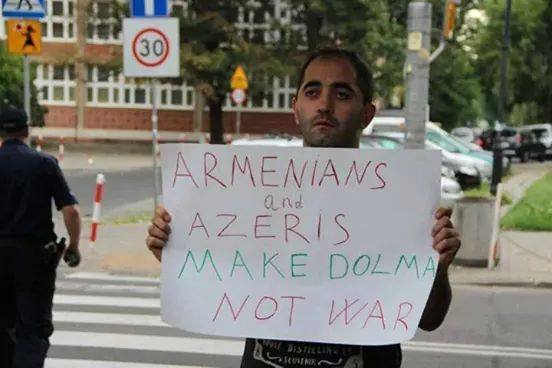

As part of the project, Assistant Prof. Uğur Kara assessed Turkish politics from Armenian genocide to the present. He talked about “Academics for Peace”. Participants listened to songs in Azerbaijani and Armenian and sang along. 6 people from Azerbaijan, 4 people from Armenia and 2 people from Turkey took part in the project, which has the purpose finding alternative solutions to the problems in two countries that stem from Karabakh conflict. However, it should be noted that the real acquaintance and intimacy is formed outside the activities of the project. Even when we were cooking “dolma” (stuffed vegetables), we realized how similar our cultures are and we use same words. Everybody was laughing each time we found a common word; we talked about human rights violations in both countries and discussed the effects of Karabakh conflict.

Some of the participants told that their friends are arrested because of their opposing views and though they are aware that it is dangerous to take part in this project, they don't regret to be there. Some of them haven't told their reason for coming to Turkey to their families. İlkin's family lives in Şamkir and she got really surprised when she realized how much I know about Şamkir. Sharing the wine that she brought from Şamkir and talking to her was the greatest success of the project for me. I know that one day we will go to Şamkir together and have a cup of tea there. Mentioning that he loves Tigran Hamasyan and Civan Gasparyan, İdgar said: “I am sure that my grandchildren and my fellow Spartak's grandchildren will sit here and laugh together one day. I believe this.”