Baronyan had always been running counter to Armenian clergy and elites whom he criticized satirically, and he lived in reduced circumstances because of his conflict with those circles which, in Baronyan's opinion, had been managing the economic resources of the society in accordance with their own interests. Even when he found out that he got tuberculosis at the age of 45, he hadn't given up resisting. (*a Latin phrase meaning “one corrects customs by laughing at them", which was used by French poet Jean-Baptiste Santeul (1630-1697) for the first time.)

According to famous linguist Hraçya Acaryan, the word "yerkidzank", meaning humor in Armenian, is derived from "yerkedz" which have meanings like "ripping, splitting, crossing out, marking". In the light of this explanation, we can say that there is a parallel between the purpose and direction of "humor" in the course of human history and a history of "yerkidzank". This article is about Hagop Baroyan who is considered as the founder of "yerkidzank" that is fueled by the strength and will of resisting the power and expressing the bare truth, and Baronyan's “disappearance” and “return” in the language he created and in the city he once lived.

Humor and Baronyan

Printing activities increased as part of the Westernization efforts that were accelerated by Edict of Gülhane. The effects of these activities on Ottoman media in general facilitated the development of the humor press and accordingly the humor literature, which was at an immature stage in Ottoman Empire. Undoubtedly, this “modern humor” originating from social and political issues appealed to certain people who are literate, well-read and have reasoning capacities and this fact led to a humor with criticism. As historian Irene Fenoglio put, this characteristic of humor constituted a threat and a potential devastation for the state. The Ottoman humor, which started to develop in 1850 especially with the development of Armenian magazines, was banned right after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78.

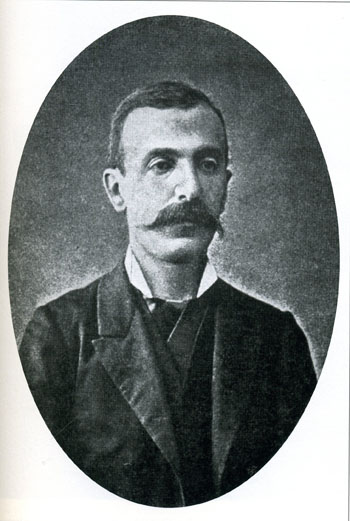

The most prominent figure of 1852-1887, which historian Anaide Ter Minassian determined as the first stage of Armenian humor**, is Hagop Baronyan (1843-1891), who had never given up expressing the bare truth regardless of his situation.

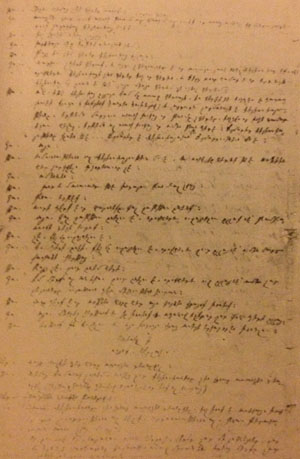

Baronyan's handwriting

Baronyan's handwriting“Next generations”

125 years ago, on May 27, 1891, Hagop Baronyan died of tuberculosis at the age of 48. Unlike almost all of his contemporaries, he was a writer who gained fame during his lifetime. Some people deemed him worthy of love and some deemed him worthy of hate. With almost 10 influential humor magazines that he issued in Ottoman Turkish and Armenian and his plays and essays, he left his mark on 1870s and 1880s, which was the era during which Istanbul-based Western Armenian enlightenment in economy, politics and culture developed rapidly.

Baronyan had always been running counter to Armenian clergy and elites whom he criticized satirically, and he lived in reduced circumstances because of his conflict with those circles which, in Baronyan's opinion, had been managing the economic resources of the society in accordance with their interests. Even when he found out that he got tuberculosis at the age of 45, he hadn't considered abandoning his struggle against those people, whom he had considered as the most important obstacles to the development of the society. He had always believed that the policies of those people can lead the society nowhere and more importantly, he had never given up resisting under any circumstance.

One week before his death, he didn't have enough money to buy the medication that his doctor in Surp Pırgiç Hospital prescribed. He had to sell the old issues of Khigar, which he stopped issuing in 1888, door-to-door and take the money that his students from Getronagan High School saved up for him; however, it is known that Baronyan had never obeyed in his life. Once, some people advised him to be less critical and he said, “I will be tortured. I will be subjected to oppression. It doesn't matter, since the next generations will immortalize my name anyway.” Is this prediction of Baronyan proved to be right? What is left from this writer, who is referred as “Armenian Moliere” and considered as the founder of Armenian humor?

What is left from Moliere

During the second half of 1880s, when Abdulhamid's oppressive rule was increasing day by day, Hagop Baronyan continued contributing to some Armenian newspapers in Tbilisi, which was the political and cultural capital of Eastern Armenian world at that time. Thanks to this, he became a famous writer among Eastern Armenians, compared to his contemporaries. Despite the fact that Yervant Odyan (1869-1926), who took over the torch of Western Armenian humor, lived abroad during 1890s and 1900s when Ottoman Armenians were subjected to great political predicaments and massacres, and Ottoman Armenian humor couldn't have grown on its motherland, the great influence that Baronyan's works created in 1870s and 1880s increasingly went on until the Second Constitutional Era and 1915 Armenian Genocide. It was a time when Baronyan's cult works like ‘Adamnapuyjn Arevelyan’, ‘Azkayin Çoçer’ and ‘Medzabadiv Muratsganner’ had been published over and over within the empire and abroad. On the other hand, given 1915 genocide which caused a fatal damage to the Western Armenian society, it is surprising to see that humor magazines published in İstanbul and Baronyan's works were still drawing interest in the years of armistice, between 1918 and 1923. In a time of great political chaos, ‘Şoğokortı’ was published in 1920 and ‘Kağakavarutyan Vnasnerı’ was published in 1923. Undoubtedly, the greatest effort of that time was Hovhannes Setyan's attempt to publish Baronyan's collected works (the first volume of the series “Azkayin Çoçer” was published in Istanbul in 1924, but the following volumes couldn't have been published). These publishing activities that have the purpose of making Baronyan accessible to Ottoman Armenian society indicate that Baronyan's works had a great role in the efforts of “Veradznunt” (renaissance) that had been tried to be realized on a political and cultural slippery slope after 1915.

In the republican Istanbul

François Georgeon characterized the early republican period as a time of dismissing the Ottoman humor. According to Georgeon, there are two main reasons for this: (1) Kemalist revolution, like all the revolutions, was serious and disturbed by the power of humor and (2) With the tragedies happened during the last years of the empire and the foundation of Turkish Republic, the ethnic-religious diversity of the empire, which was the core of the Ottoman humor, was destroyed. The disappearance of Baronyan's humor with the republic should be approached in this regard, but the social and intellectual crisis of Armenian society after the genocide should be considered as well.

On the other hand, during the same period, in the emerging Armenian Diasporas, especially in Paris, Cairo and Beirut, people continued to read Baronyan and his works had been published, though the numbers were not that great compared to previous periods. The silence concerning Baronyan in Istanbul was started to be broken in the late '50s and early '60s (which was paralleled by Baroyan movement in Soviet Armenia). In Yerevan, there was an effort for publishing Baronyan's collected works in 10 volumes, including his articles published in newspapers and magazines and this effort made an impact in Istanbul as well. As a result of the efforts of a group of intellectuals who got down to publish facsimiles of several works in Armenian under the roof of Alumni Association of Aramyan School, two volumes containing Baronyan's most famous works was published in 1961-62. Armenian literature circles responded this movement and Marmara newspaper editor Rober Haddeciyan published his book on Baronyan's personality and writings (“Hagop Baronyani Mdermutyan Meç") in 1965. However, in '60s, this interest in Baronyan's works couldn't have been maintained and those books were the last Baroyan books in Armenian published in Istanbul. And Baroyan himself was forgotten since 1999, when a group of intellectuals made a statue of Baroyan built in the yard of Ortaköy Armenian Church, after finding out that Baronyan's grave, which was supposed to be in Ortaköy Cemetery, had disappeared.

“Erecting his statue”

Freud, after his book “Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious" published in 1905, discussed the relation of humor to the unconscious in his article titled as "Der Humor". He writes, "Humor has something of grandeur and elevation." And adds, "Ego refuses to experience the pains caused by external reality and be influenced by the impacts of the external world. Humor doesn't obey, but challenges." It wouldn't be wrong to suggest that this characteristic of humor intensifies when it comes to political satire. In other words, it can be said that the purpose of satire is to defeat the current order which is formed by the rulers and works for the rulers in every instant.

But, why haven't the humor in Armenian society, which was a more rooted tradition compared to other peoples in the empire, survived? Why was there no notable humor publication or even a mediocre humorist in the republican period? Or, let me ask a simpler question: Why did humor become forgotten? Why did Hagop Baronyan, who devoted his life to resistance and saying “this cannot go on like this!” under any circumstance, become forgotten in his own language and city?

As a person who got to know Baronyan through black and white copies of his works in Dadyan and Getronagan and witnessed Baronyan's “absence” and “return” during my university years, I guess I have the right to end this article with a personal note.

When I started to study Russian language and literature in Istanbul University in 2005, I was eager to write a paper that compares 19th century Russian and Armenian humorists. My excitement died away as I realized that I have to go from door to door for accessing even one or two copies of Baronyan's works in Istanbul, whereas it is possible to find Russian copies of his works in Moscow. I talked to an elder about this issue and he said, “Hagop Baronyan, ha? We erected his statue!” He told me that some important people from Istanbul Armenian intelligentsia gathered together, collaborated with the Patriarchate and erected Baronyan's statue in Armenian Church in Ortaköy, where Baronyan once lived. And when I asked how I can find his works, he replied my question with another question like all wise people do and said, “It is a tough thing to do. Why don't you write paper on his statue?”

Edirne Greek School. Baronyan, who improved himself rather than being a good student, went to Arşagunyan Elementary School and Gymnasion in Edirne for about a year in 1857.

Edirne Greek School. Baronyan, who improved himself rather than being a good student, went to Arşagunyan Elementary School and Gymnasion in Edirne for about a year in 1857.This story led me to Rober Haddeciyan's book “Hagop Baronyan Veratartsav" (Hagop Baroyan is back, 1999). In this book, Haddeciyan writes about Baronyan's imaginary visit to Istanbul, assuming that he would come to Istanbul without a second thought if he found out that there is statue of him in Istanbul. Visiting Armenian schools, churches and feasts and seeing plays and concerts, Baronyan sees the efforts of prominent figures of Istanbul Armenian society for keeping the society alive and leaves by saying that "There is no humor material and need for me here!" But, what does the absence of Baronyan indicate? Is it true that Armenians don't need Baronyan anymore? Referring to the Latin phrase in the title of this article, does the absence of Baronyan indicate the fact that there is nothing to be corrected by humor in Armenians' current situation? Armenians lost the humor and are contented with remembering Baronyan only by a statue of him, who is the founder of their own humor literature; is there a possibility that these facts prove that Armenians' capacity to get free from the oppression that they have been subjected to for centuries, to resist and to say the bare truth is also hold captive? Or, let me finish with a more simple question, which doesn't concern Armenians directly: Can you imagine that Moliere is not commemorated in Paris, where he lived, created and died, on the 125th anniversary of his death?

**According to Anaide Ter Minassian, the second stage is between the beginning of the Second Constitutional Period and 1914, the third and last stage is between 1918 and 1923.