Every single day, some terrible news about the immigrants from Syria comes to the fore. So, in these days, we would like to share the visual diary of the forced migration that the father and grandparents of our photography editor Berge Arabian went through. In 1930, they hit the road from Diyarbakir to Aleppo. The exhibition that was opened in Diyarbakir on May 23 will visit Istanbul and Erivan, and the book that is based on this exhibition is being prepared now. Armenians are one of the communities that history challenged with migrations and they had always been migrating in the Middle East which is stirred by civil wars. This story, which is like a reversed migration, is rather an expression of longing. It is like a gloomy “uzun hava” to the lost home, Diyarbakir.

In 1930, my father, an Armenian who was born in Hazro in the province of Diarbakir, moved to Aleppo, Syria along with his family. He was nine years old at the time and the family had been living in the Armenian neighbourhood of the city of Diarbakir for the previous two years. The move was not a choice but a necessity. Having lost most of the members of their respective families and relatives at a young age during the 1915 genocide, my grandparents had grown up and gotten married to each other in the wake of the dark days of the massacres. The human losses, forced islamasization and the persecutions by the locals because of their Christian-Armenian past, had forced my grandparents to flee Hazro and take refuge in the city of Diarbakir. But even that move had not put an end to the persecution they felt as entities of a minority in the new Turkish republic. Thus, a decision was taken to leave the ancestral homeland by fleeing to Syria where many of their friends and distant relatives had made their new home.

Spring 2013, my friend Ozcan Yurdalan phoned me to invite me to participate in discussions around doing a visual/multimedia project for the 100th year comemoration of the Armenian genocide. Some preliminary meetings took place during which my part was to give ideas as to what kind of projects could be considered by the participating photographers. As an example, at one of those sessions, I explained how for many years I had wanted to do a visual travelogue of my father's family's flight from Diyarbekir to Alleppo around 1930. I had always wanted to reroute the smugglers' caravan road they travelled on to get to Syria. This was just an example. Well, those meetings somehow came to an abrupt end and for almost a year there was no news about the project. Then one day, Erhan Arık from Nar Photos phoned and said that the work to realize the 2015 project was going to resume under the auspices of Nar Photos and that they wanted me to participate by doing the travelogue project on my father. Things started moving, funding came from Heinrich Boll foundation and along with the women's 4Plus Collective from Armenia and NarPhotos in Turkey, I became a participating photographer in the project.

I wanted my travelogue to be about longing. The longing that I had seen in the eyes of my father and my grandparents for a place called Diyarbekir. He had never spoken to me about this trip. But throughout his life, the word Diyarbekir was everpresent. Diyarbekir was his nostalgia. In Qamishly, where I was born , then when we moved to Beirut not one gathering with family friends passed without stories about Diyarbekir and the old days. Always with longing. A painful longing. I eventually grew into a middle-aged man always hearing about Hazro, Lice( where the rest of my clan comes from) and Diyarbekir. To the point that in 2007 when I came to Turkey for the first time, I wanted so much to see what these names were about. I went to Diyarbekir and from there to Hazro and then to Lice. All along I had thought that being there, I will be able to see the old neighbourhoods where my roots come from. We, the grandchildren of the 1915 generation are sometimes so naive and ignorant about our elders' background. I kept telling people that my family came from Hazro and Lice and the locals kept asking, “but from which village?” Then only I understood how little I knew about my roots. They had never spoken in detail and we had never asked: closed matter. What is lost is lost forever. And later when we moved to Canada, this longing became embodied in the word Qamishly.

Qamishly became their nostalgia, and mine. I had left behind me the soil where I was born and had arrived on foreign shores. Just like my father. He longed for his Diarbekir and I for my Qamishly. Diyarbekir....Qamishly...Diarbekir...Qamishly... where does this longing stop? From father to son, is this sad pain the only inheritance we merit? In the end, what is the difference between him and me? Him longing for Diyarbekir for so many years and me for my Qamishly since I left at the age of 8. Like him, I have lost my songs. Like father, like son. The travelogue story had to be his story as well as mine. Our story of Longing.

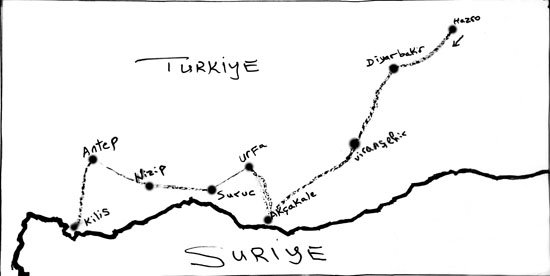

I found myself roaming the streets of Diyarbekir. Imagining my child-father playing, walking and just being. İn the Armenian neighbourhood, I saw him in the faces of the children on the streets. I imagined all my elders in this city. And then I saw their ghosts at coner streets, in windows, in shops...This was where they had come to this world. I found myself on the road from Diyarbekir to the border gate in Oncupınar, Kilis. For 4 days my road companion Husametin Bahce and I travelled through smaller country roads, to the best of my knowledge as to what the real route could have been almost 85 years ago. All I knew was that they left Diyarbekir for Alleppo and eventually settled in Qamishly. My only help had come from Asdghig and Maro Turbendians in New Jersey. As children, their father and my grandfather had survived 1915 together in Hazro. After both our families settled in Qamishly, they had stayed life-long friends. As a child, Asdghig had listened attentively to their stories whenever the two elders had spoken about their past in Diyarbekir. She shared some of their stories with me as well as found for me a rough route of the Caravan that in those days used to last 8 to 10 days. Husametin drove me as close as possible to that route, while I took photographs through the car window or often told him to stop so that I could photograph from outside the car. It is strange when you do not have something precise in your mind to photograph. But I tried to see through the eyes of my father. A 9-year-old child at that time. What could he have seen? What could have fascinated him? Who did they meet on the road? He had never spoken to me about this trip. But in the end I became the child he was. I saw through his eyes and deep inside I cried with silent tears because the journey had ended and I had left his land, my land behind me, forever.

***

In a way it is good to have done this story. I am still doing it. I am realizing that truely, my father’s departure story, which I tried to recreate with the little information that I have and with all the little bits and pieces, there is no complete story. I only know a few things. unfortunately when I was young, I did not listen well. And they did not tell me in detail or in a way so that I could carry this story, their story, to the next generation after me, or to the ones I love. So in a way to have come here and to have taken this journey from Diyarbakir to Kilis, without knowing if I am in the right track or at the right places that they traveled through, is not important. Because what is important now is that for so many years, in my mind I had been trying to piece together a complete story. And it is very difficult to know what really happened. How they went through these roads, with new hopes to start a new life. For me also, it is the start of a new life because I am leaving behind me all the mystery. All the painful mystery that I have always tried to imagine. Therefor I have created my own story. I have retraveled and retaken the same steps I think they did. Whether the right ones or the wrong ones, I think that I did my own journey and left behind me unknown details which I never had. But for me it is as if it is a fresh start with a new hope, a new beginning. It is like cleansing this heaviness that has been inside me for so many years. Always imagining my child father , a child on the streets of Diyarbakir. Imagining my grandfather, washing or cleaning in a courtyard. Imagining everything. But now, I do not need to imagine anymore. I now know. This was the journey that was calling for me. And I took it…I took it and it embraced me totally and now Diyarbakir is a new Diyarbekir… with a new hope

Celal* is singing such a song of longing... such a song full of sorrow. I have been listening to him, 3 times.. 4 times. And little by little all this longing is rising inside me. I miss you. I miss Qamishly. I miss my father. I miss my childhood... Where did this longing all begin from? Where? from Qamishly? From my childhood? From the time all my elders left Diyarbakir? But this longing is so powerful sometimes that my chest wants to blow up. I can not bear this pain anymore. All my life , all my life living with this longing. it is sometimes unbearable… It never stops.

* Celal Güzelses a Diyarbekir Kurd musician (1899 -1957)

I am thinking of the young Syrian refugee boy at the border, Mulham, and I miss him too. I miss him… I want to hug him to take his pain away. He had said to me,” your pain is worse than mine…I will go back to my Halep when the war stops but you...you have been longing for Qamishly for 50 years and you have not been able to see it again. It is too much to long and not to have.”

I just want to shout here. To scream and take out this 50 year pain that I am carrying inside me…

Everywhere on the journey, I met Syrian refugees. They are everywhere. In small towns… on the road…. some of them are cotton pickers, some of them are clearing rocks and on vast lands… sitting on the streets. Everywhere... But when my father and family had to leave Diyarbakir and went to Syria, they were like these refugees… with nothing on their backs… with nothing in their pockets. Almost... They stayed in a refugee camp. It is strange that 80 or 90 years later the children of those people who accepted them, helped them or shared with them some human compassion, have now come to the same lands that my elders had to leave…. Seeking the same refuge in a place where at least they can feel safe. And yet, the story does not end here. In other places, in other times, this same forced exchange will always happen. People will always be forced to leave their ancestral lands. Lands that they have known for a very very long time. A land where they drank its water. They breathed its air. They are always forced to leave their land and start a very long, painful journey. Starting a life full of memories. Memories that start from their childhood, their youth. And there is no going back. Landless they will be. Once you leave, it will never be the same. And that’s the tragedy of it…. The tragedy of Human history.

My heartfelt thanks to my dear road friend Husametin Bahçe who kept replaying Celal to make me cry.