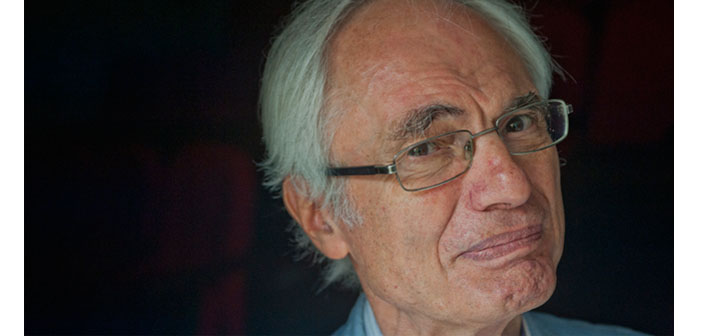

Known as the greatest living Armenian composer, Tigran Mansurian was in Istanbul for a special occasion. Although I was initially overwhelmed by his presence, thanks to his kindness and sincerity, our interview soon turned into a sweet conversation.

Commissioned by the 43rd Istanbul Music Festival, the premiere of Mansurian’s work titled ‘Sonata da Chiesa for Viola and Piano, In Memoriam Gomidas Vartabed’ was held on the evening of June 10 at the Surp Vortvots Vorodman Church with a concert titled ‘A World Premiere with Kim Kashkashian & Péter Nagy’.

Mansurian told me about his friend Parajanov, composing film scores, the feelings he has had while visiting Turkey for the first time, and the essence of his talent which I describe as genius, but which he prefers to call ‘the truth’. Unfortunately, the limited space of our newspaper’s pages do not allow me to share with you this conversation in its entirety; so the rest will remain with me…

What would you like to tell me about your life?

I am a musician, I compose. I studied for four years at the Romanos Melikian Academy of Music, and for five years at the Gomidas State Conservatory, and then studied for a further two years for my PhD. I spent my entire education life in Yerevan. My friends from the region, I mean all my Russian, Estonian and Ukrainian musician friends from the 60s are today world-renowned names. I, too, have composed since the 60s, and my compositions from that period continue to echo and live on today. Because I was prohibited from leaving the Soviet Union, for quite a long time I could not be present at venues where my compositions were performed. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, I try to go everywhere. My compositions are performed in places where I, too, can travel to now. I still live in Yerevan. Ah, and I no longer teach.

Why were you banned from leaving the Soviet Union?

I don’t know… Probably because ideologically, I wasn’t on the same side as the Soviets. I was just one of those marked men who were banned from travelling abroad.

“Parajanov would transform even the simplest things in such ways… He would elevate them from the ground into the sky, and then, take them even higher than the sky. He would conjure up incredible symbols from very simple objects, giving them artistic forms. I tried to do for sounds what Parajanov had done with images.”

Parajanov was also banned, wasn’t he?

Yes, we were in the same situation. He was a very close friend of mine.

How was working with Parajanov?

It was 1969, and I was 30 years old when Parajanov asked me to compose the score of ‘The Colour of Pomegranates’. “I am travelling to Kiev, I’ll come back when you’re finished,” he said, gave me the film, and went. There was no sound in the film, but the images were complete. For three months, I worked every day, from 9 in the morning until 9 in the evening. It was fascinating work. Parajanov would transform even the simplest things in such ways… He would elevate them from the ground into the sky, and then, take them even higher than the sky. He would conjure up incredible symbols from very simple objects, giving them artistic forms. I tried to do for sounds what Parajanov had done with images.

“My approach changes entirely when I am composing a film score. Because the music I make for a film does not belong to me but to the film, and every film has its own unique music. So I become a different person from one film to the next.”

In what way are your film scores different from your other compositions?

It’s a completely different kind of work. My approach changes entirely when I am composing a film score. Because the music I make for a film does not belong to me but to the film, and every film has its own unique music. So I become a different person from one film to the next. I have composed scores for more than hundred films, and each work is different. But the music that belongs to me, that has stayed the same over the years. No doubt, some things change, but I can say that the essence of my music has always remained the same.

I feel that composers are part mad, and part genius. Would you describe yourself as such?

If I could observe myself from the outside, I could perhaps comment on that. Yet since that is impossible, all I can say is that I am what I am. Nevertheless, no one has described me as mad as of yet.

Please don’t misunderstand me, it is only because I cannot imagine how those sounds appear in your mind.

No, no, it’s not an idea that I oppose; it’s just that I am unable to comment on how I appear. But I can say this about producing: There is a truth within me, and when that truth meets with the work I am doing, then I know I am doing something right. For instance, imagine my music as a house, I would want someone who enters that house to feel well, to feel that he or she is part of that house. If there are six of us in that house, then this person should be the seventh. In other words, he or she, too, takes the truth of that house to heart.

I should then ask what the source of that truth is.

I love Armenian music. Our culture has been conveyed to the present day from very ancient times. For instance, ‘Anganimk’, from the 5th century… ‘Anganimk’ is a hymn that takes me back 1,500 years. In a single second, I go back 1,500 years and return to the present day. This journey is my wealth. And this journey of immense wealth has been travelled by a great number of people throughout history. The work of each and every one of them has been inscribed along this path.

In addition to this, I believe that the language a musician speaks is his or her greatest teacher. You constantly speak and hear this language. Every language has its unique phonetics and intonation. For instance, in some languages the emphasis is on the final syllable of the word. That is how it is in Armenian, and also in French; but it is entirely different in Russian… So in the works of a musician who speaks Armenian, you observe influences unique to that language, and that musician becomes ‘the musician of the Armenian language’. I, too, am a musician of the Armenian language.

So, especially in consideration of the peoples living on these lands, it would not be wrong to differentiate between Armenian, Kurdish and Turkish music, would you agree?

Yes. The fact that music is influenced by language, I wouldn’t even discuss the validity of that. However, it is not only language that influences music; the body’s movements, the place you live, the way you live are all part of the equation. If you live in a mountainous area, you move accordingly, the terrain shapes your gait, doesn’t it? Or if you live in the desert, you encounter different landscapes… When you walk across the desert, you always see the same thing, and there is an idea that forms in your mind. Then, suddenly, a tree appears before you, and faced with this new landscape, the way your perception and brain operates undergoes a change. The changes in your environment will be reflected in your music. The rhythm of nature, as much as the rhythm of language, influences your music.

What do you think about the fact that not everyone listens to classical music, or does not have the means to do so?

Music responds to people’s desires in different ways, satisfying them to various degrees. You might want to comprehend the phenomenon of God, or to become God, to understand the sky and the universe. Or, in contrast, you might only want to eat, enjoy eating, and have music accompany in your enjoyment of food. Whatever the gauge your expectation is from music, that defines the kind of music you listen to.

“For with much wisdom comes much sorrow,” says the Holy Book. In other words, people, since they shun sorrow, do not want to know much, or understand everything. That is why people prefer easy-listening music. For instance, it is easy to listen to the music the great majority of young people love. Because you know how the rhythm will progress; from beginning to end, it is either boom-boom-boom, or ba-boom, ba-boom, ba-boom; maybe a second sound is added on top, a la-li-la. Nothing changes, and knowing that there will be no change reassures you. But that is not how classical music is. Various musical forms possessing various qualities come together, and they progress simultaneously.

People no longer want to talk about important things; they want to talk about simple things. They shy away from what’s difficult. It is considered embarrassing to make grand statements these days, they laugh at you. Quality has been sacrificed in all things for those who want to lead an easy life. And so music has also departed from classical music, and approached what is easy. So that is the overall situation; people no longer want to deal with problems, they want to entertain themselves.

How do you see the future?

I read somewhere that states would be condemned to the pages of history in the next century. I mean, if humanity doesn’t consume itself fighting over nuclear weapons, then I think we are not on a bad path at all.

I was actually asking about the future of classical music.

Compared to previous centuries, we have the chance to record many more works. Classical music reaches a wider audience now, and anyone who wishes so can listen to the works of the great masters, that is a beautiful thing.

They say you are the greatest living Armenian composer. What do you make of that?

That’s what they say. I had the chance to meet greater names than myself, and I hurt inside because they are no longer with us. I am the only one left… And for me, they are the great composers.

Finally, could you tell us what these three names mean for you: Gomidas, Aram Khachaturian and Tigran Hamasyan.

Gomidas is our father, he is the father of us all. He brought us everything about us, laid it all out before us and said, “Here, this is what we are”. And the whole world saw this, began to discover Gomidas, and that discovery continues to this day.

Aram Khachaturian came to say, “We lost one and a half million of us, but we continue to live”. And he made that heard with such a voice that the whole world heard him, and they came to know him and Armenian music.

Tigran Hamasyan is a very sweet musician. His singing takes me back to Armenia. Whether with his piano or his voice, he shows that he is a child of those lands. He has a very rich memory. It’s fascinating how he has such an immense memory. I can’t tell whether the music is borne from him, or he from the music…

‘We used to be afraid when we saw the Turkish flag; and now I have Turkish flags all around me’

When did you move from Beirut to Yerevan?

In 1947. I was 8 years old. The return to Armenia had begun during those years, and my family was one of many who decided to settle in Armenia.

So your family are Anatolian Armenians…

My mother is from Maraş, my father from Diyarbakır, they met at the orphanage after the slaughter, and they set up their home in Beirut. My mother was very stubborn. I love the stubbornness of the people of Maraş, I have that same quality.

What does 1915 mean to you?

We, four siblings, we grew up with the stories my mother told us. She didn’t tell us many, but we remember the ones she did very well. But these are not issues that should be talked about, or remembered at this moment.

Then tell me what it feels like to visit Turkey for the first time…

It is as if I am counting the minutes. An hour passes, then another… It’s not easy at all. Every moment I experience is different from the next. One moment I am calm, the next moment I am not… I will be staying here for a week; it’s going to be difficult. As I just said, I’m counting the minutes. I’m witnessing things that I’m not used to at all. We used to be afraid when we saw the Turkish flag; and now, with Turkish flags all around me, I realize that this fear is unnecessary, and that’s a new thing for me.

* I would like to thank Vahakn Keşişyan, my hero, thousands of times for facilitating my communication with Mansurian during the interview, and for transcribing this interview that was conducted in Armenian, and went on for hours.