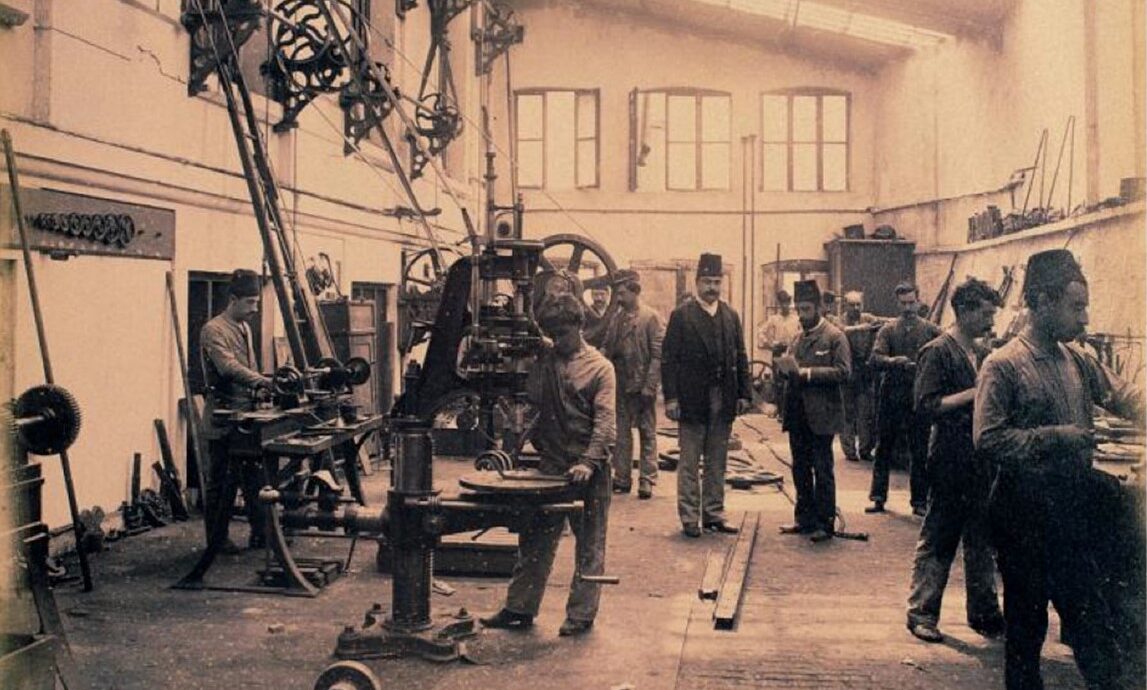

In the 19th century, as wage labour relations became widespread in different sectors, crafts, agriculture and then industry, both the capital and the working class in the Ottoman Empire, which, like every empire, was built on a class society, had a multi-communal, multi-religious and multi-lingual structure. According to Çetinkaya, there is a rupture that must be mentioned here: ‘the construction of the nation-state, the process of nationalisation and the extermination of different communities in various ways through methods such as ethnic cleansings, genocides and exchange’. This political project also meant cutting off important elements from the working class and the working class movement, and cutting the way for socialist and Marxist movements.

The symbolism invoked by the 100th anniversary of the Republic has led to a review on many topics; these collective glances have been ongoing since 2023. The recently published ‘Workers in the First Century of the Republic’ is part of the 100th Year of the Republic Series prepared by İsmet Akça for the History Foundation Yurt Publications. M. Görkem Doğan, who has studied topics such as the labour movement and the politicisation of the labour movement academically, as well as following the same topics ‘on the street’, has undertaken the editing of this volume.

There are many ways of reviewing. Such times offer the possibility of a holistic view, as well as the opportunity to intervene in the historiography that has been established until then, to revise it or to put forward an alternative. Doğan says that their priority in determining the framework was to underline the “new” tendency that has emerged in the last 30 years. The view that is meant by “old” and whose traces can also be found in the 75th Anniversary of the Republic Series, is in fact widespread beyond the academia; at its root, in Doğan's words, is the assumption that “Turkey is a rural agricultural country, so workers and their mass mobilisations are not fundamental social issues.” “The first century of the Republic of Turkey is, from a very high level, a story of industrialisation, and therefore the class struggle, labour and the issues surrounding them cannot be seen as a fringe issue. They had a significant impact on the first century of the Republic,” Doğan says. Accepting 1923 as the zero point in explaining everything and focusing on the “Industrial Revolution” can be added to these established assumptions.

Non-Muslims missing from the class

Who is called a worker, how did the working class as a social movement emerge in these lands, through which structural transformations capitalism was constructed; the historical continuity required while reading all these questions makes it necessary to look back to the pre-Republic of Turkey. We can open a wider parenthesis by asking Y. Doğan Çetinkaya, who does this in his article in the book and argues that it is difficult to understand the Republic without focusing on capitalist modernity, about the place of non-Muslim workers in the Ottoman labour force.

In the 19th century, as wage labour relations became widespread in different sectors, crafts, agriculture and then industry, both the capital and the working class in the Ottoman Empire, which, like every empire, was built on a class society, had a multi-communal, multi-religious and multi-lingual structure. According to Çetinkaya, there is a rupture that must be mentioned here: ‘the construction of the nation-state, the process of nationalisation and the extermination of different communities in various ways through methods such as ethnic cleansings, genocides and exchange’. This political project also meant cutting off important elements from the working class and the working class movement, and cutting the way for socialist and Marxist movements. This vein, which developed after the 1870s and became more effective in the legal field after 1908, remained as an accumulation and heritage remembered only by some historians. This rupture, which is very important for the history of social struggle, was of course accompanied by the nationalisation of capital.

Çetinkaya describes it as follows:

“As in Europe, the national bourgeoisie's understanding of national economics and nationalist political parties were behind the construction of the nation-state. This was also a process of confiscating all kinds of capital of non-Muslim communities. For many years, only nationalist intellectuals and state cadres were seen as the subject of this. However, there was a very active Muslim/Turkish bourgeoisie behind it. We were always told the story that a national bourgeoisie was created out of nothing. However, they were the subjects of this process. Moreover, the working class, which from time to time fought together with elements from different communities within the framework of class brotherhood, was also divided on the axis of national conflict. The Muslim/Turkish working class was also made an element of the national project. Today's ruling classes and their institutions are the result of this project. The groups that are considered as the two sides of today's political and cultural polarisation are actually partners in this project and they are the same. I always say that the roots of the AKP and the CHP in the Ottoman Empire converge in the Committee of Union and Progress. Both in terms of nationalism as a political project and in terms of class.”

Women in trade unions

In ‘Workers in the First Century of the Republic’, in addition to Doğan Çetinkaya and Görkem Doğan, articles by Can Nacar, Hakan Koçak, Süreyya Algül, Emel Karadeniz, Aziz Çelik, Necla Akgökçe, Selin Pelek, Mustafa Kahveci, Görkem Akgöz, F. Serkan Öngel, Nuran Gülenç, Hande Beyza Doğdu focus on the processes of workers' subjectification, unionisation and different periods of the labour movement in Turkey. Since such an article is neither enough for this corpus nor for 100 years, it would be better to proceed with parentheses.

In the parenthesis of women, who are always missing in historiography, Necla Akgökçe looks at this century through the presence and absence of women in trade unions. Akgökçe's review of the literature also presents a series of women's profiles waiting to be researched in depth and placed in their place in history. For example, the sit-down strike organised by men and women at the Cibali Tobacco Factory of the Reji Administration in 1904 and the women workers we know to have participated in it, Odisya Tabrizya, Mari Neccar, Raşil Eşkenazi. Or the 120-member Women's Clothing Workers' Union, which also participated in the 1st of May in 1910. Reyan Ozan, a welder and mechanic at the factory, who was among the founding members of the Bakırköy Cloth Factory Workers' Union in 1946. Journalists Neriman Hikmet and Saadet Varanel, who were among the founders of the Istanbul Press and Publication Head and Arm Workers Union in the same years. Seher Kerpiç, one of the founders of the Istanbul Ortaköy Tobacconists' Union, who was tied with a rope and taken from Ortaköy to the Sirkeci Security Directorate, as recalled by Zehra Kosova in her memoirs. Those women who were wounded in clashes during the vigils of the legendary Bereç Strike in 1964, which lasted for 41 days, but then - with the exception of Fikriye Odaman - did not appear in the union administrations. Dervişe Koçoğlu, who was elected president of the Bandırma, Balıkesir, Çanakkale Havalisi Tobacco, Muskirat Food and Auxiliary Workers' Union in 1952, was the first in this sense, and despite her many speeches at union meetings, little is known about her, and after her death she was only remembered as Alparslan Türkeş's half-sister. All these women are waiting to be researched and their stories told.

While the academy is also becoming a labourer...

In this sense, Akgökçe's article is also a call to the academy, but on the other hand, the last quarter century has been a period in which academic studies on labour history have diversified and deepened. We can make this part a parenthesis that extends beyond the volume “Workers in the First Century of the Republic.” M. Görkem Doğan attributes this abundance to the proletarianisation of the academy, and says, “We see labourers because we have become labourers.” In the same time period, the pressure on academic autonomy and freedoms has increased even more. How does this affect labour studies? He is referring to Oya Baydar's (then Sencer) thesis on “Working Class in Turkey: Its Birth and Structure” which was not accepted.

“At that time, the thesis was not accepted because the working class was seen as a threat. It is easier to work on issues related to workers in academia with a class perspective today compared to Oya Hoca's period. In the last thirty years, unfortunately, since the working class was not seen as a threat by the rulers, we have not been persecuted for our theses or writings. The objectionable topics of these thirty years have been minorities, the Kurdish issue, the demographic history of Anatolia, Alevism, the character of the AKP regime, etc. If we manage to make them see the working class as a threat again, the answer to the question will change in the future.”

A new parenthesis appears here. It is not easy to fill it in, but perhaps M. Görkem Doğan can answer it, as someone close to both the academia and the street, who has looked back on a hundred years of the history of the working class and its organisation with a cool head. In these days of wealth transfer disguised as a crisis, when the loss of all kinds of rights in wage labour is systematised and large segments of the population are so clearly impoverished, how can we explain the failure to raise a mass objection that can counter the attack without underestimating the existing resistances? How can looking at the last century of workers open our minds about today?

Movement in the global factory

Although it is not possible to simply repeat anything, Doğan mentions the importance of knowing the successful organisations of the past when constructing today's needs. He concludes that since the end of the 1990s, working class organisations have not been able, or even attempted, to put forward an organisation model in line with the new workers' sociology. When the collapse of real socialism was coupled with the political economy transformation in the 90s, trade union structures that could not keep up with this transformation could not become the vanguard of mass movements. In the “global factory” of neoliberal globalisation, everything is already fragmented.

“‘Factory production lines are now part of cross-border production lines. In the fragmented structure of the global factory, production is fragmented, labour is fragmented. The OSB (organised industrial zone) deserts all over Anatolia are the result of this. This fragmentation makes solidarity among workers more difficult and makes the dense reserve labour army in the countryside, especially in rural China and India, accessible to the global capital class. In short, this global factory cannot be organised with the Keynesian-era practices of united enterprise unionism, and in fact it could not be organised. Today's worker is distant from the union. The wisdom that the worst union is better than no union is no longer relevant. In the first decade of the 2000s, when the idea of Umut-Sen was developing, I was a first-hand witness to many examples where small workers' assemblies in Anatolia who wanted to organise in enterprises of around a hundred people, which is the standard of the global factory, were not organised by the existing unions because they were told that 'it isn't worth it.'"

In the first of the articles in the book, Doğan looks at the post-12 September period, reading the ‘heroic but inconclusive’ TEKEL resistance that started at the end of 2009 as a signpost, and in the second article he looks at the post-2010 period. In 1988, the unionisation rate calculated by Aziz Çelik based on the number of workers benefiting from collective bargaining agreements was around 27 percent; in 2012 this rate dropped to 6 percent, the picture is clear. The other article analyses the Metal Storm, which started in 2015 at Oyak-Renault in Bursa and spread to the metal sector, and the transformation that brought it into being. Afterwards, a new actor emerges from de facto strike to de facto resistance; DGD-Sen, founded in 2013, focuses on independent unions such as İnşaat-İş, Bağımsız Maden-İş and PTT-Sen. This is a new form of organisation, a new language of struggle.

Despite everything, Doğan said, "The global factory in Anatolia is stirring. Today, there is no OSB that has not seen resistance, the workers are angry, they are aware of the situation" he says, “We still haven't built the organisation model that will make the struggle of the angry and uprising workers politically meaningful and make political intervention, I think this is what is missing”. How and in what way this deficiency will be filled will determine the "second century" of the workers.