Weeks ago, when the Israeli army ordered the people of the south via X (formerly Twitter) to leave their homes and 'relocate to safer places,' large numbers of refugees arrived in our areas. Zaven, a clothing vendor friend in Bourdj Hammoud, told me, 'Three women came to my shop, around 50–60 years old, dressed in black and wearing headscarves, asking if I needed workers; they’re looking for work. My heart shattered. I already don’t have work for myself; I couldn’t say anything to them.' Not long after, a woman stopped me in front of my house, asking, 'Do you know of any houses for rent?'

ARAZ KOJAYAN

A few minutes before midnight on October 3, just as my mind, so in need of rest, was barely drifting into sleep, a loud sound and a mild tremor shook me out of bed. It wasn’t fear that overwhelmed me; my subconscious is full of survivor experiences, the most recent being just days before, on September 27, and a few years ago, on August 4, when I survived the Beirut port explosion without physical harm. This time, it was my astonishment, my detachment from reality, that overwhelmed me. How is it possible to witness such heavy bombardment and continue life as it is?

As I write these lines, the Israeli army is bombing and leveling the southern village of Mays al-Jaba in Lebanon, leaving no stone unturned, while a shepherd from the village of Kfarchouba sets out with 1,200 sheep, walking about 50 kilometers to reach the southern Bekaa Valley with 500 sheep. On the morning of October 30, my friend Maryam, originally from the village of Rmeish in the south and now living in Beirut, left a message on my phone: 'Bahiya is fleeing; the (Israeli army) has issued evacuation calls for their area as well.' Bahiya is our friend from Baalbek. In response to my helpless text message to her, she replied in a short, breathless voice note, saying, 'We can’t come to Beirut; there’s no road. We’ll settle here for now. Pray for us, Araz.'

Weeks ago, when the Israeli army ordered the people of the south via X (formerly Twitter) to leave their homes and 'relocate to safer places,' large numbers of refugees arrived in our areas. Zaven, a clothing vendor friend in Bourdj Hammoud, told me, 'Three women came to my shop, around 50–60 years old, dressed in black and wearing headscarves, asking if I needed workers; they’re looking for work. My heart shattered. I already don’t have work for myself; I couldn’t say anything to them.' Not long after, a woman stopped me in front of my house, asking, 'Do you know of any houses for rent?'

The policy implemented here bears no difference from the colonialist and imperialist appetites reflected in our readings and studies, protected by impunity, as they continue to destroy every trace binding the people to its land. Not only have more than a million people been uprooted from their land and homes in this war, but the possibility of their return has also become extremely difficult, considering the extensive destruction Israel has carried out. In addition, at least 17 incidents of Israeli weapons in the south have been recorded containing white phosphorus, a chemical substance that burns and completely destroys even nature. If this is not the alienation of natives and farmers from their land, then what is it?

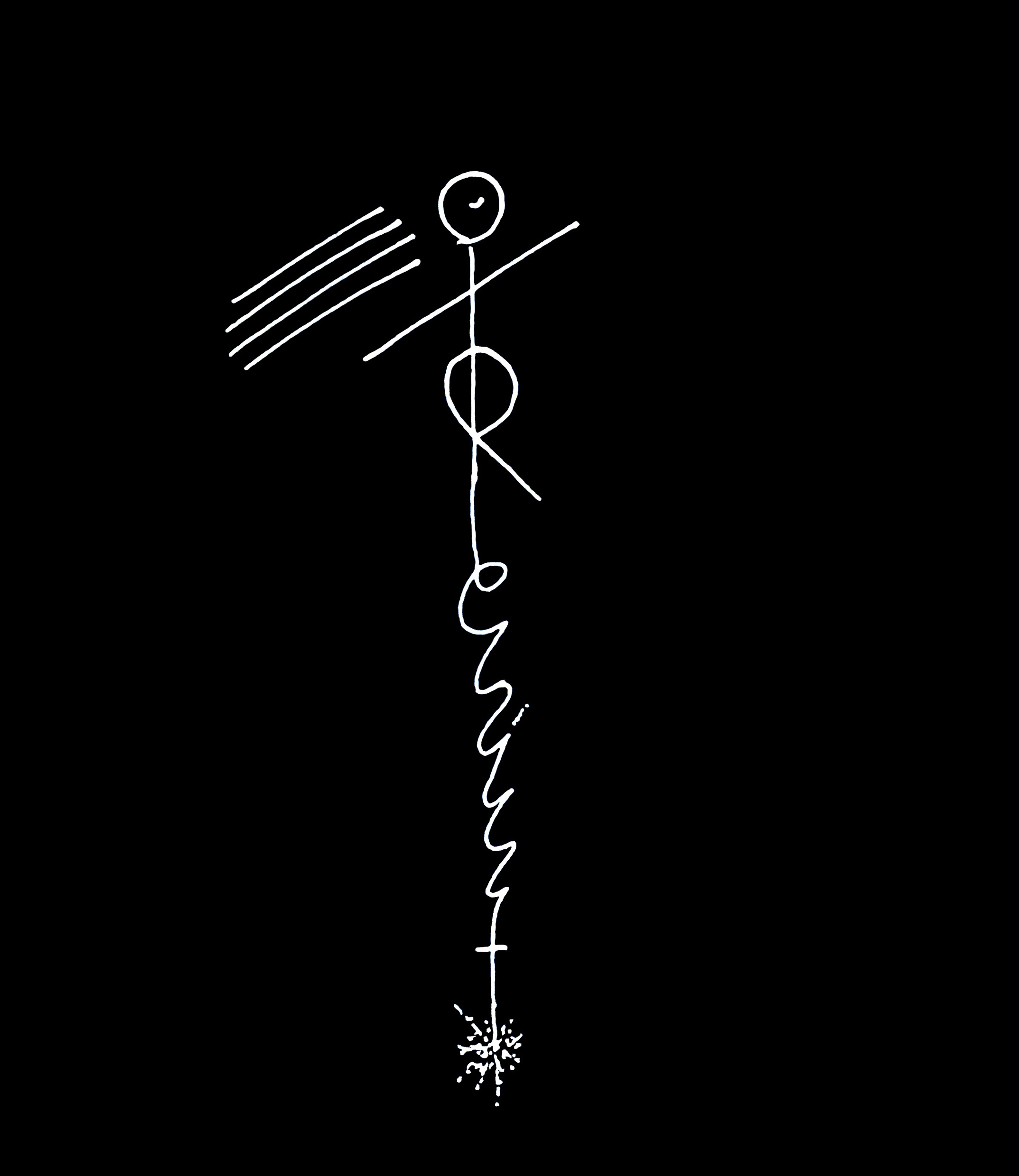

As I shared my war diary of Lebanon with friends in the Parrhesia Collective, many observations emerged from our discussions; one of them was the reality of me always falling onto the side of the oppressed. Both as an Armenian and as a Lebanese, in both my distant history and the course of my life, both my homelands have always been subjected to the politics of colonizers and have had to devote their lives more to surviving than to living and creating on their lands. How easy it is to sympathize with the struggles of nations from afar, yet how much strength and mental capacity it requires to keep standing and surviving amid crises as a strong individual. Naturally, your heart fills with gratitude when you see waves of solidarity from the people of those colonialist states in support of the oppressed and the victims. Of course, it’s a different matter when, for various reasons, that same solidarity is not shown toward all oppressed nations and victims. During my conversation with friends in the collective, I expressed that I would prefer to remain on the side of the oppressed rather than the oppressor. My friends couldn’t remain silent to this statement and proposed a third way—to resist—because the oppressed are not depressed; they have the capacity to resist. And though we will carry these stories of war and trials to the end, we will also have our stories of resistance.

Naturally, it isn’t easy to continue life as it is. The definition of 'normal' doesn’t even hold a common understanding across all places and times. Our current "normal" is following the instructions for an arbitrary displacement of people on X, trying to play a kind of prisoner's bay in order to survive the disaster. How long will this “normal” continue? If we live, we will see.