Following Chienne d’Histoire [The Barking Island], a wordless film from the perspective of the non-human, where we only hear the dogs’ voices, Avedikian’s documentary Histoire de Chiens [Dog Stories] was screened. This documentary, focusing on the relationships between Istanbul residents and street dogs 100 years after the 1910 dog massacre, differed from the first film in that it presented people’s perspectives on their relationships with dogs. The film momentarily eased the heaviness left by the first film with its style.

TAMAR GÜRCİYAN

“Stories are much bigger than ideologies. In that is our hope”

—Donna Haraway

I first learned the story of the dogs being sent to Sivriada as a child while looking at Sivriada from the bare rocks left from the period when the island was used as a quarry, on the hilly road behind Kınalıada. This story resurfaced with Serge Avedikian’s film Chienne d’Histoire [The Barking Island] following the recent law.

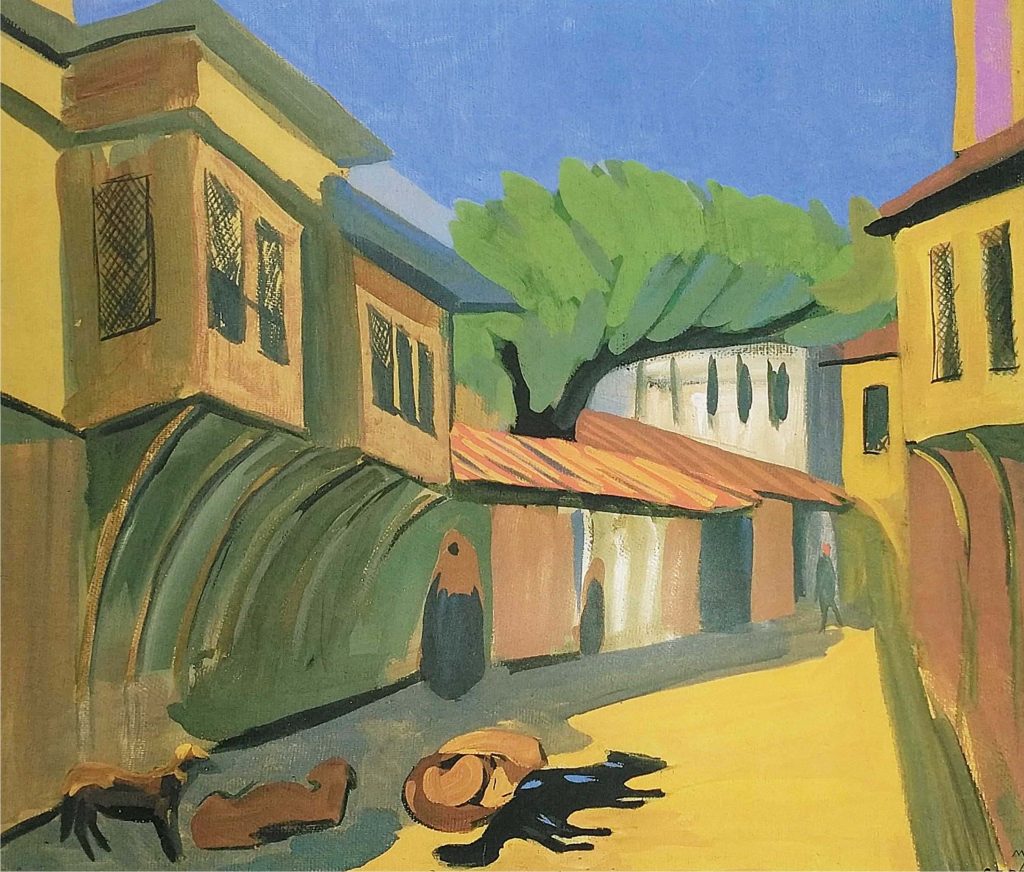

Last week in Berlin, an event titled Beyond the Bark was held, moderated by me, organized by AKEBİ (Activist Action Union Against Racism, Nationalism, and Discrimination), Armenian Animal Aid (AAA), and Armenian Movies Day (a monthly screening of films by Armenian directors). The event began with a short animated film. As I revisited Thomas Azuélos’s watercolor drawings in the film, I thought of Mardiros Saryan’s paintings of street dogs from his 1910 visit to Istanbul. In his autobiography, Saryan mentions that dogs were an inseparable part of Istanbul’s streets and that people walked calmly amidst stationary dog islands. He describes Istanbul’s dogs as an integral part of the city’s morphology of the time.

Following Chienne d’Histoire, a wordless film from the perspective of the non-human, where we only hear the dogs’ voices, Avedikian’s documentary Histoire de Chiens [Dog Stories] was screened. This documentary, focusing on the relationships between Istanbul residents and street dogs 100 years after the 1910 dog massacre, differed from the first film in that it presented people’s perspectives on their relationships with dogs. The film momentarily eased the heaviness left by the first film with its style.

In the film, the owner of a café in Cihangir district of Istanbul, said that violence against dogs stems from a historical understanding that views the other as different and foreign. After the film screening, Ph.D. student Orhun Yalçın from Munich’s Ludwig - Maximilian University discussed this understanding’s connection to violence practices, using examples of Ottoman colonial activities in Ionnina, Egypt, and the Euphrates-Tigris basin in the 19th century. He explained the long-term consequences of these activities using Rob Nixon’s concept of "slow violence" (translated as "sürüncemeli şiddet" by the presenter). According to Nixon, slow violence is a type of violence that gradually reaches its peak following deliberate decisions and encompasses events like environmental degradation and climate change, which have long-term effects.

Yalçın used this concept to describe the Ottoman practices of social and political domination based on primary sources and invited us to consider the long-term and invisible impacts of violence rather than its short-term effects. Yalçın’s discussion covered the displacement of Greek people due to the draining of marshes in Ioannina, the local people who died during the construction of the Mahmoudiyah Canal in Egypt, and the animals like cats, dogs, and birds that perished as a result of the land's diminished productivity after Armenians left, touching upon the non-human aspect of the story alongside the human one.

Post-humanist thinkers call us to move beyond human-centered perspectives and recognize the subjectivity of the non-human through pluralistic or decentralized viewpoints. Donna Haraway, in her book The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness, draws attention to the active subjectivity of the non-human—animals, cyborgs, and the mechanical and organic—in ecological, social, and other systems. She examines human evolution through the relationship with the non-human and depicts dogs as an inseparable part of the co-evolution of humans and animals, highlighting the complex relationships between the two species.

According to her, there cannot be just one companion species; at least two are needed to make one. Therefore, interspecies kinship is inevitable. To establish this kinship, setting aside ideological narratives and re-evaluating storytelling and historical narration to create new narratives that can harbor hope may open up space for human and non-human coexistence. The Beyond the Bark event was a small but valuable step in this direction. I hope that the stories we heard, the new narratives, and the realities emerging from these narratives will invite us to rethink our relationships with our surroundings and animals and to establish more sustainable forms of relationships. Woof.