Issue of migration preoccupies many people in Turkey as the political atmosphere gets increasingly tenser. In a time like this, we wanted to get together with Armenians of Turkey who migrated to Armenia, the closest and most distant neighbor, during the hard periods of recent history and report their first-hand accounts. These people, who told about their lives with a great sincerity, revealed human's power and hope of starting over.

There is a long queue in

front of the counter opened for the flight to Yerevan from Istanbul.

Most of the people waiting for handing their baggage over are

Armenian, the plane is going to Armenia and almost all passengers are

speaking Turkish. When I catch the eye of the counter clerk, who are

staring at the queue that he sees four times in a week, he shares the

question that may be preoccupying his mind for a long time: “All of

these people are going to Armenia. Really, what's the deal with

Armenia?”

There are many Armenians who migrated from Turkey to Armenia. Some of them went in late '70s and there are young people who made this decision recently. Though each of them has different motives, expectations and dreams, there is one thing certain: on the streets of this former Soviet country, you hear Turkish and Western Armenian very frequently.

“I was in Turkey, when Madımak was burned down”

Sabri Bey was sitting next to me during the flight; he was an Armenian from Bitlis. In the queue, he was right behind me and I gave him my share of baggage allowance, since he had too much to carry. In his hand baggage, there were beans and rice for him, kadayif for his youngest daughter and filo pastry for his Armenian citizen wife to whom he married in 1995. He goes to Istanbul twice a year and takes whatever they miss from Turkey with him. Sabri Bey heard what the clerk said. He said that he hears similar things in Armenia as well: “They asked me why I came. I say that's none of their business!” I also asked why and he said, “I was in Turkey, when Madımak was burned down.”

Heading to Armenia in '90s, Sabri Bey has 3 kids younger than 20. His two daughters are Armenia citizens and his son is a Turkish citizen. He is exempted from the military service in Armenia. Kids are working in Yerevan and Sabri Bey was the first one who brought the drip irrigation systems to the country. They all live in Etchmiadzin.

“Life led us here”

However, the first destination of people migrating to Armenia is certainly Yerevan. Every one we called in Istanbul before hitting the road named a cafe and told us to start from there. The cafe, which was opened by Lerna Balıkçı Özder with her husband and a partner, is called “Cosi E La Vita”. Quoting from Lena, “La Vita, meaning life. Life led us here.”

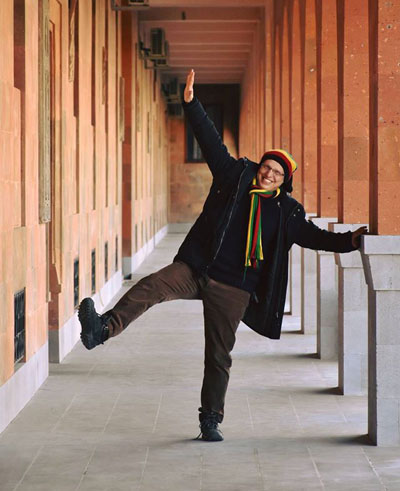

We headed to this country following the ones who were led here by life. After a 2-hour journey, Nişan welcomes us. Studying history in the public university since 2013, Nişan is called “the headman of Yerevan”. He is the person that every one from Turkey knows and trusts. He will accompany use in Yerevan and we will listen to his story as well. His closest friend, 24-year-old Turcologist Gevorg will be our interpreter with his peculiar way of speaking Turkish. The moment he sees me, Gevorg asks: “Istanbul is the most beautiful city in the world. It is the best. Why do these people come here?” I have nothing to say and he answers his own question: “They live their identity here, that's why.” I learned from him that Turcology is the third high-scored department in Yerevan. Every year, about 50 people are graduated from the department. And job opportunities are quite a lot compared to other departments. Gevorg makes a living by working as an interpreter and adviser. His family is from Yozgat, he was born in Yerevan. He visited many cities in Turkey, but he has never been to Yozgat: “I feel offended by this situation. I am afraid that I would feel like a stranger and probably I will feel like this.” Diyarbakir is his favorite after Istanbul. He asks about Diyarbakir; he feels sorry about its current condition. Talking about Surp Giragos Church, he says: “They destroyed something that belong to us. Now the state has it, but what is it good for?” Nişan and Gevorg speak Turkish to each other, not Armenian. Nişan says, “I speak Western Armenian and he speaks Eastern Armenian, but we speak the same Turkish.” After eating a piece of fried dough as breakfast, we head to Yerevan to visit a place where this Turkish is spoken most frequently. I should note that Gevorg had a little vodka.

Milestones that made people hit the road

Milestones that made people hit the road

In Lerna's life, there had been two days that are milestones leading her here. One of them is April 24, 2011; the day she lost her brother Sevag... In the past, they were dreaming about opening a cafe together. Sevag told her, “Let's open a cafe, after I complete my military service.” She serves the dishes that Sevag liked in La Vita; souffle is one of them. Lerna says, “Souffle is called 'lava cake' here. We managed to make people like it. They love to eat it. Sevag also liked pastry very much, but they don't know filo pastry here. We offer it for now; I hope they would like it. Olive oil dishes and topik are not eaten here. They don't know about the Armenian cuisine in Istanbul.” She says that she came here with a sudden decision and she talks about the process leading to this.

Lerna was working in an event organization company and her husband Şant was an executive in an investment firm. Their partner Alex Fındıkoğlu is from Perşembe Pazarı. Opened 6 months ago, Cosi E La Vita is located on the favorite street in the city; there is a William Saroyan statue across and famous Cascade right next to it; Cascade, a huge stairway, is the most popular touristic place in Yerevan. Cafe is like an association of Armenians of Istanbul. As you can guess, there are Istanbul dishes and “meze”s on the menu.

Jewelry dealer Sarkis Hanzovyan is sitting at another table in the cafe; he came here from Aleppo 9 months ago. He comes to us when he sees Nişan. Actually, he came to Armenia to marry, but he couldn't find what he expected and he will go to Latakia. He says, “It is nice there now.” He says he is well off. He asks why I am in Yerevan. After I told the story, he starts to talk about a friend in another city. I ask, “Is he from Istanbul? May I talk to him?” He says, “No, he is from here. He is Armenian.” People in Yerevan don't see Istanbulites as Armenian. Lerna also complains about this. Their cafe and menu have yet to attract enough attention of locals of Yerevan. However, three partners are determined to achieve this.

A new life, a new hope

Lerna says that she wasn't a part of the Armenian community back in Istanbul. After her brother Sevag fell victim to a hate crime when he was doing his military service, she stopped going to church. “I lost my faith. There were a lot of unanswered questions. I hit rock bottom.” The other milestone in Lerna's life is May 30, 2013... “It had been almost 2 weeks that we lost Sevag. One day, my father said that he has no reason left to live. That day, my husband said to my father, 'You are going to be a grandpa.” Şant and Lerna are married since 2006. Their plan was to spend the money they earn for traveling, they didn't plan to have a kid. Lerna says, “I looked at my husband. This was something new. It wasn't possible, I was in a really bad mood. He said, 'A child is necessary for them to recover.” May 30, 2013 is the birthday of their son Odin...

“Well, there is a planet like this”

“Well, there is a planet like this”

Odin was a relief for the family, but he also gave a new fear to Lerna that led her to Armenia. “As Odin grew up, I was thinking that I cannot send this child to do military service. I thought that Armenia may be a way out. I made my decision in a month and came here.” I ask what they knew about Armenia before coming here: “First time I realized that there is such a country was 2012. Before that, I wasn't interested in Armenia. I didn't know where it is, what its people are doing,” and she adds: “I got off the plane and when I saw the Armenian letters, I said, ' Well, there is a planet like this.' Then I regretted that I have never been here. I confronted the fact that there is a country speaking my language. I said to myself, 'Things are good here now. Why didn't I come here, when things were bad?” I asked what if Armenians don't like Sevag's favorites dishes that she serves. She says, “I wouldn't feel sorry. They don't know about the western dishes. This is east. At first, I was angry that they don't know about topik. However, now I think that being judgmental is unnecessary.”

Decisiveness of coincidence

La Vita's partner Alex Fındıkoğlu decided to move to Armenia in 1997, after he coincidentally met an Armenian citizen in Taksim. Back then, life in Armenia was harder and going to Armenia from Turkey was even more difficult. After this coincidence, they started to write and call each other. Alex grew more and more curious about Armenia and got on a bus to see Armenia in 1999, when he was 18 years old.

He starts to tell his story: “I was on my way to Armenia. Everybody was speaking Armenian and I was feeling really happy.” Back then, trailers were accompanying the buses to Armenia for carrying the extra load. They waited for 2 days in customs of Georgia and Armenia because of that extra load; the journey lasted for 70 hours. After this 70-hours-long trip, the bus stopped near the center of Yerevan, around the old fire station. Alex remembers that the city was like a dungeon back then. He set foot on Armenia for the first time on October 27, when one of the most important incidents in the history of Armenia took place: he witnessed the Armenian parliament shooting that killed 8 deputies, including the prime minister and the chairperson of the parliament. He spent 5 days and returned to Istanbul. He went to Yerevan by bus again in 2000 and 20o1. Then, he took his relatives and friends. He says, “I wanted people to like here.” He got a satellite dish and started to watch Armenian TV channels. When you look at 35-years-old Alex's passport, you see the story of a person who went to Yerevan for 45 times, until he settled in Armenia on April 2015. Alex says, “My affection is so deep that I have no words to describe it. I don't think about returning at all. Maybe I will regret, but I want to live here at this age.” He sounds determined.

“This is a country”

So far, Alex help around 20 people to get an Armenian passport. “Every one can contact me. I am a citizen of Armenia. I don't feel like a stranger, I may marry here, why not?” Not every one supported his decision to move to Armenia: “All of my Turkish friends wished me good luck. On the other hand, my Armenian friends said, 'Are you stupid? Why are you going?' They talked behind my back about my reasons to go to Armenia. However, once they came and saw here, they said, 'We mocked you a lot. We disapproved your decision, but you did the best.” Alex also talks at length about the problems in Armenia and the possible solutions to those problems. He says, “In Istanbul, we live as a community. However, this is a country; people need to understand this. There are every kind of people; thieves, bandits, liars, murderers... In a Muslim country, where we have to conceal our identities, we should be more careful compared to here.”

Putting the pieces together in Yerevan

Unlike Alex, the life that led people to Yerevan has not followed a smooth course for every one. This is true for 63-years-old Haço whom we met in La Vita as well. Everything in his life mired down until he moved to Armenia. He found himself here and put the pieces left in Istanbul, Venice, Grenoble, Paris and New York together in Yerevan. He has been living here for 25 years.

“In 1965, they taught us a song. The original lyric is 'red wine of Armenia', but they told us sing as 'red wine of the yard'. In Armenian, words 'Armenia' and 'yard' sound similar. They said that using the word Armenia is dangerous. Then I realized that there is a country called Armenia in this world.” Haço goes on: “Actually, I forced myself to love here. I was leftist; I had a sympathy for the Soviets. A socialist Armenia... As a nation, our future is here.”

“I had nothing else than walk out”

Haço says that he searched for a place to live his Armenian identity at its most natural throughout his life and he is always open to discovery in this sense. They sent him a seminary school in Venice, when he was 13. “I left Turkey at that age because of my admiration of Europe. I lived there and learned the Armenian culture there. There were times that I don't like it, they were saying nationalists things, I was a bit rebellious,” says Haço. Back in Venice, he stood up against the priests; he thought that he cannot live like that and returned to Istanbul. He went to Mıhitaryan High School, his history and geography teachers were Turkish. They were mocking with the way he speaks Turkish. This made him more conscious about his Armenian identity. He thought that they were trying to humiliate him. During his second time in Istanbul, he thought even priests are better. Saying that “I realized that I had nothing else to do than walk out”, Haço left Turkey in 1980 for good. He went to Italy, France and Soviet Armenia. He went to university in Yerevan, but dropped it after a year. He met an Armenian woman born in Romania; her family was from Kayseri and she was living in New York. They got married and lived in New York for a while. They had identical twins there. Now, his daughter is a PhD candidate writing a thesis on Kurdish-Armenian relations before 1915. His son is working as a programmer in a US-based company in Yerevan. After spending 3 years in the US, they moved to Armenia in 1991 with the independence of Armenia. He is here since then. Meanwhile, he got divorced, had many jobs ranging from interpretation to journalism, managing a photo studio and a pizza shop. He also worked in embassies. His smile has never disappeared as he talks about all of these: “I like Italian food, but Turkey has a special place in my heart.” He talks about the beauty of Van and the monasteries there. He says, “Armenia is my greatest discovery,” and adds: “The only thing that keeps people outside Armenia alive is the hatred against Turks. People here don't need such a hatred for live like Armenian. You start to feel that hate in childhood in diaspora. Once you are here, it wears off, because you realize that there is lots of things other than hate. Being Armenian doesn't mean not to like Turks. Here, being an Armenian is a natural thing.”

People of Musa Dagh in Masis

People of Musa Dagh in Masis

Next day we head to Masis city to meet a family that moved here during the Soviet period. Majority of the residents of Masis are from Antakya; there was a Yazidi village once. Before the Karabakh War, there were also buildings where Azerbaijani people lived. Now, on the way to Masis, we mostly see a wide flat land, except from a car market somewhere along the road.

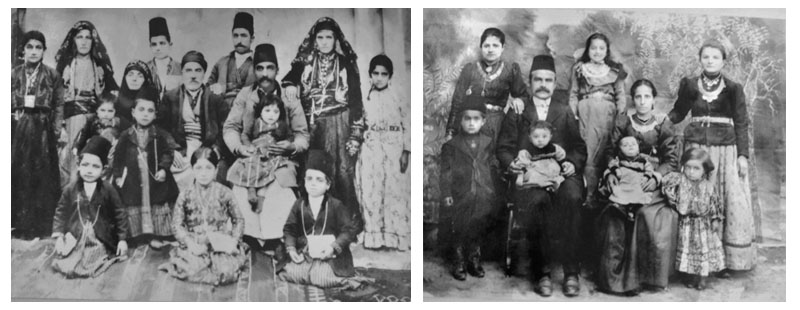

75-years-old Keğam Mardiryan is the eldest person of the family we visit. He moved to Soviet Armenia with his wife Kınar and 8-years-old son Vartkes in 1979. When they came to Soviet Armenia on October 24, 1970, Soviet regime gave them 3 options for accommodation. Without having a profession, Keğam Bey thought that he could be a car mechanic. His wife was a cook in Feriköy School back in Istanbul. She started to work in the cafeteria of a factory in Armenia. They have been living in the same place for 40 years. Vartkes Bey is 50 years old now. He and his Armenian wife Lilit have two daughters at the ages of 20 and 21 and an 11-years-old son. Vartkes Bey calls for his son Hrant. He asks his son where he is from and he answers: “I am from Musa Dagh.”

The family migrated to Istanbul from Vakıflı village in 1967, bought a house in Kurtuluş and finally moved to Armenia. People from Musa Dagh living in Masis cook harisa and make a vow in the third week of every September. Last year, on the 100th anniversary of the resistance, they cooked 100 batches of harisa. There are 4 or 5 more families like them and they gather together in some other holidays or special days. They still eat the dishes of Musa Dagh; Vartkes Bey's wife Lilit also learned to cook those traditional dishes. Vartkes Bey says, “I am still arguing with my mother. She doesn't buy bulgur from the grocery store. She insists to buy wheat and make the bulgur by herself. And Keğam Bey defends his wife: “The bulgur in the stores are fake, this is the reason.” Keğam Bey and the family are happy with their lives; he says that he misses only the rocket salad, which cannot be found in Armenia. Talking about coriander, he says, “There is a kind of herb here, it is like bedbug. My wife got used to its taste, but I cannot eat it, I don't like it at all.” Vartkes Bey says that they should avoid the statements implying that their culture is superior. He says, “We are all Armenians here, after all.” However, Keğam Bey cannot help asking: “Can you please bring some sweet potato seed next time you come here? I don't like the potatoes here very much.”

Disturbed by one's own odor

Vartkes Bey's daughter Hasmik shot a documentary film about the story of people of Musa Dagh titled “The Sleep of Orange” with director Eylem Şen. Vartkes Bey is also a historian. He is also interested in cultural business, he works as a tourist guide and gives tour of Ani and Van to the Armenian tourist groups. When I ask why they come here, he says: “You have to tour the places like Ani and Van very well in order to understand this. Once you see those places, this question becomes meaningless. There is an anecdote about a bird that builds a nest somewhere else because it feels disturbed by the odor, but it is its own odor. It is same with the people; we left Turkey, because we felt disturbed by our own odor.”

He tells about the rest like he is pouring his heart out: “Whatever we, Armenians, talk about, there is the issue of the moment of fracture that is going to run and run, which is 1915. They killed people, took away their culture and don't let them to maintain it. Now, when I talk to, let's say, a 20-year-old and ask him these questions, he cannot understand the issue, because his pain should be relived first. However, authorities in Turkey still call people giaour. We cannot trust that state, we think that they will deceive us again. They say that times have changed, but we still hear the stories of the ones who killed Armenians today, not the stories about the people who saved Armenians. And to crown it all, they ask me where the treasure is, when I am in Ani or Van. I am, I was the treasure brother. I was supposed to live together with you, to open a shop; we were supposed to be neighbors and be pleased with it.”

Young people with Turkey on their minds

Given the fact that many young people in their twenties are thinking about leaving Armenia, I ask Vartkes Bey what he would do if his daughter says she wants to go to Turkey. Hasmik didn't know anything about Turkey before the documentary. She went to Turkey for shooting, made friends there and her thoughts have changed. Vartkes Bey talks at length, but he doesn't have an answer. Finally he says, “Maybe it is what she should do.”

Our Turcologist friend Gevorg also wants to leave Armenia. He thinks that he can work in Russian companies. He says that young people are felt stuck. Nişan thinks that he would stay in Yerevan, if there will be some dialog projects and works conducted between the peoples of Turkey and Armenia, but he is not sure. Nişan is one of those whose path was crossed with Agos in the past. Three of us wander around the famous flea market Vernissage at the center of Yerevan.

Leaving or staying?

Gevorg says, “I don't like waverers, people have to be sure about what they want.” I like a pocket binocular dated to 1980 Moscow Olympics; it was produced for the ones who were too far away to see the games in the large stadium. Gevorg says, “If you want to buy this, then say it. Say, 'I want to buy this.' No hesitation. If you want it, I would bargain the price.” While he is bargaining, he also tries to make me like the binocular. In the end, we buy it.

Nişan is not like Gevory; his life in Yerevan is full of ambivalence. He lived in 7-8 different houses within his first 3 years. He says that some of them was in a good location but in bad condition and some of them were hard to heat. He says that he might move out again on March. Before he moved here, he visited Armenia two times. During these visits, he met Armenians from different countries. His knowledge about Armenia was limited to what he heard from his friends who experienced Armenia. I asked about his personal reasons for coming here, he talks about politics, history and some other stuff that he calls idealistic. He says that there had been some times that he felt belong; for instance, he participated in the protests of the Armenian youth in 2014 and 2015. On his first day in university, he had an argument with someone who asked him whether he is Turkish. Then, they became close friends. Nişan says that he has many close friends from university; Harut, Samvel, Zabel and Diana. Without an exception, all of those friendships were started with arguments and then he decided that they are open-minded people. Gevorg says, “Historical events still lead the Armenians in Turkey to Armenia.” He thinks that Turkey is not safe, talking about Diyarbakir and Surp Giragos once again. “Armenian community in Istanbul has a centuries-old history, peculiar culture and language, but they are disappearing day by day. There are some problems, that may be why they are coming here,” says Gevorg. “I think there are few people coming here for religious reason, but they might be fed up with Islam. They might be thinking 'We want to see women's hair and walk around half-naked.'” Nişan says that he was rather going through a period that he felt tired of his life: “I hit rock bottom in my life in Istanbul. Going to Armenia was a way for holding on for me.” His admission to the university in Yerevan was coincided with a rather good period of his life. His first days in Yerevan was hard: “I had some problems in registration, I was staying in a bad hotel. On my second week, I decided to go back. I had very little communication because of the language problem. My first month was miserable.” However, he is happy with his life now. And Gevorg is determined to take his chance in Russia.

A person from Malatya in Abovian

While we are about to leave Vernissage, we come across craftsman Stephan. He sells what he produces in his carpenter shop in Abovian. We agree to meet with him later.

Next day, we head to the workshop of Stephan Bey and his son Sevan. Yerevan takes its water from Abovian city, which is greener compared to Yerevan. Stephan of Malatya planted 18 apricot trees around his workshop. His grandson took his first step to become a carpenter like them. Back in Istanbul, he was producing custom-made furniture for wealthy families. He says that demand in Armenia is low. He mostly produces souvenirs and wooden spoons. He gives me two beautiful boxes made of walnut tree. Meanwhile, he is baking potatoes on stove.

Stephan Bey says, “We came here during a difficult time in Turkey.” He came here after September 12 coup, but he visited Armenia in 1977 . Back then, he had relatives in Armenia, Armenians of Malatya who came from France to Armenia. He was born and raised in Malatya. He lived there for 21 years: “I never returned after the military service. They had shut down all schools. Our language was going to extinct. That is why all Armenians in Malatya migrated to Istanbul.” He pulls a photo of a funeral ceremony from the chest: “Look, this is the grandfather of Hrant Dink. And this one is his grandmother.”

Owing a shirt

When they came here in 1977, they saw that they have a homeland. “It is not only about 1915. There were wealth tax and pogrom on September 6 and 7.” He says that he was in Istanbul in those times and “Turks owe me a shirt.” After I ask why, he starts to tell about it: “American sailors were there. I bought a red shirt; it was beautiful beyond words. However, I never had a chance to wear it. It was September 6 and we had to put up a flag. We had to cut my shirt; my brother was a tailor and we put a star and crescent on it. They broke our door down and they didn't do anything to us after they saw the flag. I was a single handsome young man, I wanted to wear it outside.”

He had a five-floored house in Bakırköy that he built himself. He thought, “Every ten years, something bad happens to us. It is enough,” and left with his family. I ask him what he knew about Armenia before moving. He says, “No family, people sleep around, you see that your wife is with another man..” His son Sevag interrupts: “Don't misunderstand, my father talks about the communist regime.” Stephan Bey continues, “That's what they told us. However, once we came, our relatives and everything was here. It was so safe. Women were on the streets until morning, every one was educated. There is everything. What is Turkey good for?” He also says, “Hrant was my relative. When he was in Armenia, he visited me. I said, “Son, come and live here. They won't let you be there.' And it was the last time I saw him...”