Held captive by Ottoman army, Anzac soldiers reveal rather unknown aspects of the Armenian Genocide through their journals. In the stories that came to light thanks to the studies of New Zealander historian and journalist James Robins, experiences of Anzac soldiers who witnessed the genocide are told. This interview of Robins is about his studies that reach from 1915 to the present.

You talk about Anzac soldiers who witnessed the Armenian Genocide. This is not an issue that is discussed much in Turkey. Could you please tell me to what extend Anzac soldiers witnessed the genocide, how much did they see and hear about the massacres and deportations?

These details are new to many people, including in New Zealand and Australia. I’m fairly sure that I’m the first person to link these two things together: New Zealanders and the Armenian Genocide. Most of the scholarship has focused on the major powers during the war because of their closeness to what was happening to the Armenians. For example, Morgenthau’s cables back to the US, or the German archives which revealed both participation in and resistance to the orders for execution and deportation of Armenians. But just because a country is far away from the killing fields themselves, that doesn’t mean that its citizens weren’t involved, either as witnesses or protectors or relief workers.

What I’m researching may not reveal anything new about our understanding of how or why the Genocide took place, but it does reveal what I call New Zealand’s “forgotten past”. These details are crucial to New Zealanders’ understanding of their own history, and how that affects foreign policy, or how we commemorate the First World War, for example.

I see that, in your studies, the link between Anzacs and the genocide starts with the Battle of Chunuk Bair.

Most of the New Zealanders who were held prisoner by the Ottomans were captured at Chunuk Bair, but there were a few other places as well. During the Battle of Romani in 1917, a patrol led by Lieutenant Frank Allsopp of the Auckland Mounted Rifles was captured, and there were a number of other soldiers captured at various points during the war.

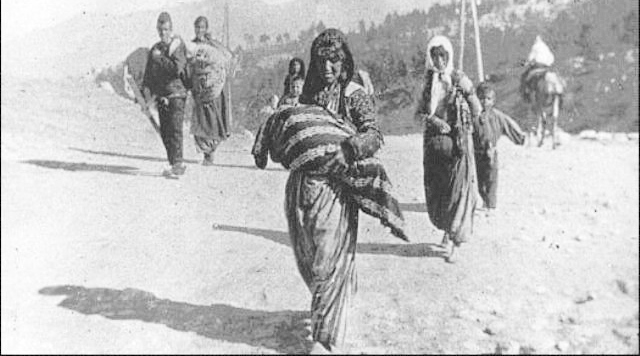

From what I can find, fifteen New Zealand soldiers spent time in Afyon. Twelve of them were captured at Chunuk Bair. A number of others were held in different places like Bilemedik, Constantinople, or Ankara, but I focussed on Afyon because there are a number of diaries written by Prisoners of War held there, and they described in some detail either the general treatment of Armenians, the deportation marches which they had seen when they were being transferred to Afyon, or noted down what other prisoners had seen, particularly the accounts of British officers.

While we were talking before the interview, you said that Anzac soldiers saved Armenians and Assyrians in some regions. Can you talk about such stories?

Australian Captain Stanley Savige went out with 22 men, including a handful of New Zealanders, to protect The Armenian and Assyrian population evacuated from Urmia. Certainly the story of Robert Nicol and Alexander Nimmo is the clearest example of New Zealanders saving the lives of Genocide victims during the war. But it wasn’t just lives that New Zealanders were saving. When our soldiers liberated Jaffa in 1917, they saved the last parts of an Armenian cemetery which had been almost completely destroyed by Turkish troops. This was one of the many acts of cultural genocide committed against the Armenians. They’re almost equally as important as the people themselves.

You also gave names of a few newspapers which have reported about Armenians during the war. Could you tell me more about such coverage? What were they about?

The genocide was widely reported in New Zealand newspapers at the time. Almost every major massacre of Armenians was reported here, in both large newspapers and small, local papers. The stories would often appear alongside the war reports from Gallipoli, or wherever New Zealanders were serving. Most of these would be cable reports from London or from bureaux in Russia where the Armenians were fleeing too. Often they were just a few sentences, but even as early as December 1915, there was a long editorial in a major newspaper which referred to the “Armenian holocaust” and the Young Turks’ “crimes against humanity”. It’s certain that many New Zealanders would’ve known what has happening behind the front lines, and would’ve had at least a basic understanding of the context.

Also, newspapers would regularly carry full-page ads encouraging donations for 'Starving Armenians'. 'One pound feeds and clothes a child for a week,' their taglines read. Echoes of these phrases can be heard in relief campaigns today. Indeed, most modern aid organizations can trace their ancestry back to Near East Relief, and their attempts to save the Armenians. “One pound feeds and clothes a child for a week” is a phrase very much like what we would read or hear today in campaigns by Unicef, World Vision, or Save the Children. Take any humanitarian crisis over the last 100 years, and there will be a striking parallel with Armenian relief efforts in the way funds are raised or certain images and phrases are re-used.

As far as I know, though there are attempts and supports for recognition, the Armenian Genocide is not yet recognized in New Zealand and Australia. What is the reason of it?

A petition has been started by the Armenian community in New Zealand urging the government to recognise the Genocide. The Green Party, which is the third-largest party in parliament, has said that it would support recognition – the first party to do so. It’s a small campaign at the moment, but there are very dedicated people in charge.

Some historians or campaigners argue that official recognition isn’t always needed, but I would say that it certainly is. New Zealand, just like every other country, is bound by a framework of international law, part of which was built by Raphael Lemkin. He invented the term ‘genocide’ precisely because of what happened to the Armenians from 1915 and the Jews from 1933. New Zealand currently sits on the United Nations Security Council – how can we be taken seriously if we fail to recognise the crimes against humanity in modern history?

And even if there weren’t very intimate links and connections between New Zealanders and the Genocide, we still have a historical and moral responsibility to acknowledge the truth. Academics, journalists, and scholars can certainly educate the public on this issue, but that can’t be the only thing done. Recognition is a powerful statement: “This is what we believe to be true”.

You are asking a question at the end of an article of yours: "This forgotten past, now uncovered, brings into question the special relationship that exists between Australia, New Zealand, and Turkey. Can New Zealand state officials stand on a platform with Turkish officials at Gallipoli knowing that they actively refuse to acknowledge the truth of what happened to the Armenians? Knowing now that New Zealanders risked their lives for the survivors?" Would you mind giving me your answer?

I think the answer ought to be ‘No’. I believe it’s completely unacceptable for New Zealand or Australian officials to stand next to Turkish officials at Gallipoli and pretend like the Genocide is something that can be ignored or whitewashed.

Now that we know these details about New Zealanders and their connection to the Armenian Genocide, we have to confront the Turkish government’s position of denial. Because if the Turkish government continues to deny the Armenian Genocide, they also deny that New Zealanders saved Armenian lives, saved their cultural artefacts, saved Armenian children for a horrible fate. It would deny that some of the things New Zealanders did during and after the First World War were actually heroic and worthy of celebrating – people like John and Lydia Knudsen, for example.

This isn’t a trivial or insignificant issue, but a topic that cuts to the heart of what New Zealanders understand about their history and their place in the world. In New Zealand, Anzac Day is a major event. Last year, the 100th anniversary of the invasion at Gallipoli was commemorated by hundreds of thousands of ordinary people – they clearly still care deeply about the issue. And it is precisely this feeling that I wanted to address when I called the article “Anzac and the Armenian Genocide”. The links and connections between these two things colour or influence the way we remember our soldiers, or remember our role in the First World War.

Further, I have argued publicly that the Turkish government has been essentially blackmailing the New Zealand government since Anzac Day celebrations began, stopping them from recognising the Genocide. You only need to look at what happened in 2013 with the New South Wales state parliament in Australia. They passed a motion of recognition, and the Turkish consul-general, later backed by Ahmet Davutoglu, threatened to ban NSW representatives from attending the centennial commemorations at Gallipoli. This is nothing other than blackmail and abuse, and the relationship between New Zealand, Australia, and Turkey has become poisonous because of Turkish denialism.

New Zealand is forced into a pointless choice. We’re forced into choosing between whether we honour our own war dead, the Turkish war dead, or the Armenians, which is ridiculous. We should be able to say that we remember and honour them all, and have equal sympathy for them.