Two weeks ago, we received a letter from Van. In the letter, there was information about a foundation that is founded by 7 friends. They wrote, “Now, we are 27 people in the foundation. We are the assimilated grandchildren of Armenians and struggling against the treasure hunters sometimes by ourselves and sometimes with the help of law-enforcement officers. It is saddening to be left alone like this, while we have been trying to protect various structures like churches, cemeteries and bridges as Muslim individuals.” The letter was signed by Ali Sulmaz from Çatak Association for Protecting the Environment and History.

Ali's letter was reproachful, but he wrote that he won't give up. He calls their struggle “a divine duty” and he wrote about their projects. They made t-shirts “Armenian Culture Restoration” printed on them; they want to give those t-shirts to children in the district and gain the support from the public. Their ultimate goal is to restore a church in Çatak. This is what they wrote.

After that, we feel that going to Çatak is essential. We stayed in Çatak for 2 days and Ali accompanied us day and night.

Destination Sortkin

Çatak is about 2 hours drive away from Van. As the locals say, “It is on the other side of the mountain.” The climate changes as we get closer to Çatak; the sun disappears and the snow-covered roads begin. There is nothing on the road, except from a police station. In order to visit the structures that the foundation wants to protect, we should always be on the road. We won't have the chance to sit down with Ali and talk to him at length. Ali will talk about his and Çatak's story, while we are on the road. Our first destination is Sortkin Village, where the famous Botan River springs...

Ali offers “Çatak tobacco” to us. I don't smoke, but Berge tries it and finds it soft and nice. He says that he doesn't like Adıyaman tobacco, because it is strong, but this is not like it. Ali begins to speak by saying, “I am Kurdish.” He is 37 years old; he was born and raised in Çatak. He has 4 daughters and does construction work. He says that he doesn't have a project now, because the market is dull. He had to sell his car. He says, “If you don't have a car in Çatak, you stand by with folded arms.” The vehicle we use is borrowed.

“I am Armenian as well as I am Kurdish”

At the beginning, Ali said that he is Kurdish but he adds, “My grandmother is Armenian. In fact, I am Armenian as well as I am Kurdish; that's why I am engaged in this business.” His grandmother Piroze's family was from Erç Village of Gevaş. In 1915, her father Sargis and his wife had to flee from Van and left their daughter behind. Piroze walked to Çatak. Osman Aga from Gravi family adopted her. She converted to Islam, when she was 13 and changed her name to Hanife.

Ali's grandfather is from a nomad Kurdish family wandering between Şırnak and Van. “My grandfather got involved in a fight in his childhood and fled to Van. Osman Aga adopted him as well and he and Hanife got married when they are 14 or 15.” According to Ali, there are 350 people in Çatak descending from Hanife. Grandparents of other people in the foundation are also Armenian. Ali says, “As far as I know, during the massacres, people usually tried to save their sons and left their daughters behind,” and adds that his friends from the foundation cannot say that they are Armenian as easily as him. They are afraid of oppression and exclusion.

Dome of the church

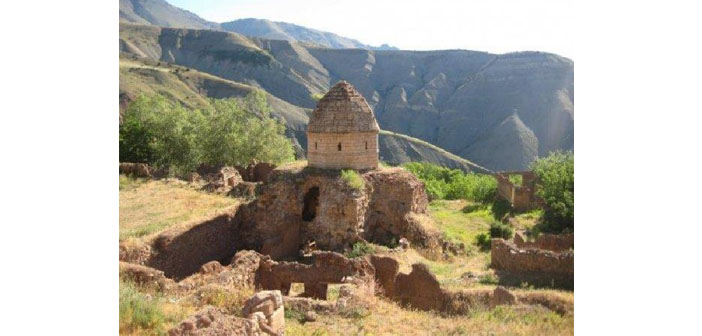

We arrive at Sortkin Village. The dome of the church is visible from a distance; the structure stands, but it is harmed by treasure hunters. The village is often engulfed by avalanches and the church has taken its share from them. The entrance is almost blocked and we crawl to get inside. Ali says that he hasn't came to the church since autumn. We see that church's floor is removed. Ali says that it was there before; the treasure hunters have just dug the floor. It can be said that there were a lot of hunters; it looks like there was a construction vehicle inside, the entire floor is carved. And seemingly, they tried to remove a huge rock on the wall. They tried to remove to see whether there is a treasure behind it, but the rock resisted. I can say that they will be back for that stone. Ali says that the locals are engaged in treasure hunting because of poverty. We enter the other rooms by crawling and then leave the church.

Once we are out, people in the house across the church wave and we are invited to drink tea at Mehmet Bey's home. Villagers watch us from the windows. They offer the herby cheese they made, village bread and smuggled tea. Ali says, “I am against treasure hunting, but it is different for the locals. When some wealthy people from Istanbul do it for pleasure, it is different. But you see the people here; only thing they have is cheese and bread and they share it with you. They are poor fellows; they have no land to cultivate. If they had 50-100 animals, they may earn some money by selling milk and cheese. It is one thing to try to find a way to make a living by treasure hunting and it is another thing to do it for pleasure.”

At first, people think that their foundation is also a treasure hunting foundation. Ali says that many people wanted to join them because of that, but they didn't accept them. He is proud of that. He says that they changed the treasure hunter image.

Tender for the village

Mehmet Bey cannot speak Turkish well; his son talks to us. I ask how they live here and what they eat. He says that they have a garden and its products are enough for them. I ask how that small garden can feed the entire village. He says that it feeds only them. According to him, there was a tender for the village, after Armenians were deported in 1915. Mehmet Bey's father won the tender. They came here from the village on the other side of the mountain. Sortkin was an Armenian village before. I ask whether the houses around belonged to Armenians. He says that all Armenian houses were destroyed. He points at somewhere and says there is only one Armenian house. But there is nothing where he points at. I ask where it is. He says it is over there, under the ground. Armenians built their houses under the ground, because there are a lot of avalanches in winter. Rumor has it that houses, market place and the church are connected with tunnels and the entrance of the church is not that small, but some part of it coincides with the tunnel. In the village, there is also a huge mulberry tree that is left from Armenians. However, they cut it down, when a child fell from it. Only its root survives.

Mehmet Bey breaks into the conversation: “I plowed this field by myself.” Once, when he was going to work on the field, he ate 16 breads. He says, “But I did 3 men's job.” The village is where the famous Botan River springs. They created a pond by building a dam on the bottom; they farm trouts there. They used to sell fish to the people who come for picnic, but now that the peace negotiations are ended, no one comes for picnic.

Mehmet Bey's son tells us that there are graves of Armenians on the mountainside. We want to go there. After a short climbing, we arrive there, but there is no grave; I mean, there is no headstones. We see crosses and writings in Armenian carved on the lowermost part of the mountain. Armenians who had to flee buried their deceased there and used the mountain as headstones. The largest headstone in the world... Ali says, “There is a cave on that hill. They stayed there for a while, but it is said that they were taken away anyway.” The graves are far away from the road and treasure hunters cannot spot them because there is no headstone. Not only churches, but also graves are targets for the hunters.

Call to the Patriarchate

Recently, Ali caught someone in the act. Foundation members heard that treasure hunters are digging the graves in Darinis Village. They went there and took a couple of valuables from them. He says that they want to give them to the Patriarchate. He says, “The Patriarchate doesn't know about us, our foundation and our struggle here. Maybe, they would get interested, if they read this.” He says that usually some dishware are found in the graves, but they have seen such valuables for the first time.

We leave Sortkin. We head to center of Çatak for visiting the other structures. After spending a night there, we will go the mountains.

Ali says, “Before you, Baron Sarkis Seropyan came here.” It was in 2010. The first ceremony was held in 2010, after Surp Haç (Holy Cross) Church in Akhtamar was opened to worship. Baron Seropyan was there for the ceremony. Ali and his friends went to Akhtamar Island for handing the leaflets of their foundation out for introducing the foundation. Baron Seropyan took the leaflet; he got surprised at first and then started to ask questions. Ali says, “Baron looks tough at the beginning”. Seropyan admonishingly asked, “How could you do something like this?” Ali says that they got afraid thinking that they might have done something wrong, but then, Seropyan started to laugh. “He came to Çatak with us. He wandered around, visited the sites and saw himself. He listened to us and appreciated what we do. But he hadn't much time, so he couldn't have spent the night and seen all the structures. Even Seropyan hadn't saw some places that we will go with you.”

In Çatak, there are 36 churches. Most of them are in ruins now, but some of them still stand. Each church has a different “rescue” story. The story of the Church of the Virgin Mary is Ali's favorite. This church is covered in snow during winter and falls on the buffer zone of guerrillas during summer; so, treasure hunters couldn't have entered there for a long time. During peace negotiations, the state built a police station there which, again, prevents the treasure hunters from entering there. You can access to the church both from Gürpınar and Çatak, but since there is no road, you have to walk there. This place is also important for the Muslims there. People who cannot have a baby had been going there and praying. Boys are named İsa and girls are named Meryem, if the praying works. There are children named İsa and Meryem in Çatak and Gürpınar.

Ali is very pleased by those children named İsa and Meryem in Çatak. He says that he is Muslim, but religious people hate them because of the foundation. He has some questions about Islam; he reads the Bible and Psalm and compares them to Quran. He wants to find out whether there are relatives of his grandmother in Armenia. He wants my help. He follows the Facebook pages that shares passages from the Bible. Ali says, “Hanife was known as Muslim like us, but as she was dying, she spoke her last will and want people to put a yellow bead in her mouth. It was the last reminder that is left from her family. There is no such thing in Islam. I think that she wanted to die as a Christian.”

At the center of Çatak

We visited 5 structures at the center; 3 of them are church, one of them is either a church or an inn -locals don't know- and one of them is Hulkan Bridge.

There are 2 churches at the entrance of the district. They are known as Herisin Church and used as hayloft storage. One of them is almost hidden; they planed the top and turned it into a house. The church is inside the house and it is impossible to see it from outside. The other one is exposed but in a very bad shape. Luckily, since it is used a storage, treasure hunters cannot enter it. However, the young boy who shows us around asks with glowing eyes whether there is treasure inside. We head to the hidden church. There is coop at the entrance, we shoo the hens away and enter the church through a tunnel. The church is in good condition. Since it is inside the house, it is not damaged by rain. Ali shows all the details and whispers, “If they know the details I know, they would bring the house down.”

The largest church in the district is the Central Church. Its roof is collapsed and people grow vegetables inside. The owner of the church, Ferit Akdeniz works in a public institute. I ask him if they are Armenian descent. He says, “Perish the thought! God created me as Kurdish, but I am very happy with the cultural heritage of our district. I would gladly contribute to a restoration work.” When Ferit Akdeniz said, “Perish the thought,” Ali wanted to laugh, but he contained himself. After we left there, Ali says, “This is a reflex. In the past, calling someone Armenian was an insult, but now they got used to it. In the last 30-35 years, people began to question certain things. Right or wrong, good or bad, we gained the right to question. It wasn't like this before. We were seeing some structures in the village we went. We were asking why those structures are there. We began to question it. Our purpose is to restore one of those structures.”

We also go to Hulkan Bridge and Zeve Church. They call it church, but we cannot see any traces of a church, like engravings or crosses, in this building with a police station view. We drop by the church and Ali points at the plain across the bridge and says, “There are 6 churches over there. We want to form a walnut grove there. We still eat the walnut that Armenians planted.”

In Çünüş

Next morning, Özcan Örek, one of the founders of the foundation, gets behind the wheel. The road to Çünüş village is though; some parts of it is covered with snow. Özcan is a truck driver; he passes through these roads every day. He transports sand, briquette, cement between Van and Çatak and supplies food to the villages. Özcan says, “All people in the foundation are laborers. There are waiters, construction workers, plasterers and so on...”

Çünüş is located on a mountain top. There is no one on the road to the village, except from shepherd's dogs. The single lane is covered with stones and snow and it is very close to the valley. Berge and I get afraid when the car corners, though Özcan drives on low shift, because we are in the car. At one point, the road is completely blocked by snow. We want to walk, but Özcan manages to take us to the village by car. The village is located so high above the sea level that we feel like we can touch the top of Artos Mountain.

The monastery is preserved so well that we are surprised. Şükrü Nikcar, one of the members of the foundation, welcomes us at the door. There was a hole on the roof, but Şükrü Nikcar had it repaired. He says, “We have been maintaining this place for 30 years. If it wasn't for me, it would have been collapsed by now. It rains and snows too much, but not a single drop has been falling here.” There are about 30 houses in Çünüş. I ask the villagers why they live there. “Armenians left here after the war between Muslims and Armenians. We settled here. They built this village for protecting themselves. They came here when there was war down there. Our folks came here for the same reason; for protecting themselves from the war against the state.” According to them, the village has been here for 700 years. One of them calls out to us: “I wish the people who built this builds houses for us!”

About a thirty years ago, the monastery had been used as an elementary school called Alburak. They say that 30 or 40 people are graduated from it. Now, young villagers are in Mersin or Adana for working. Few people are left here.

The stone throne

Rahmi Kıpçak approaches me. He is the most curious one among them. He asks me questions, looks through my notes. They call him “the grandson of Gejo”. They are teasing him by saying that they would make him the priest if Armenians come back here. Rahmi says, “They rumor that I am an infidel and they make fun of me.”

Rahmi shows me a hollow. “There was a pool for baptism, treasure hunters dug it.” He shows me a stone and says, “I kept it for you.” The stone is very old, but seemingly, it is a cross stone. There are engravings on it. The treasure hunters thought it was a map and dug around accordingly. There is an empty space in the room of the head of the church. Rahmi says that there was a stone throne there; he hasn't seen it, but his father said so. The monastery is very well preserved, but Ali says, “If we had financial support, it would be in a much better condition today.” We cannot go to the other villages because of the weather conditions. We say goodbye to the friends from the foundation and hit the road.