Following artist and researcher Hradzan Tokmakjian, we look at the needlework that women from Marash, Ourfa and Ayıntab, who survived the genocide and managed to go to Aleppo, brought with them, the differences between the needlework styles of 3 cities, the changes in those works in 100 years and the craft that mothers have been teaching to their daughters.

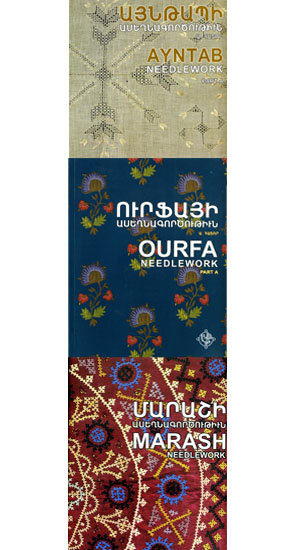

Artist and researcher Hradzan Tokmakjian carried out long-term researches on needlework of Armenian women from Marash, Ourfa and Ayıntab, while he was living in Aleppo and working as an art teacher. Tokmakjian, with the collaboration of Armenian foundations in Aleppo, complied these researches in 3 books; these books were published in Armenian and English. These encyclopedic works contains examples of needlework collected from various houses and collections in some museums, correspondences and documents. Moreover, containing the list of Armenian houses, churches and schools, these works shed light on needlework, which is the cultural heritage of Armenians from Marash, Ourfa and Ayıntab.

With Hradzan Tokmakjian, we go back to Aleppo and to the times he started painting; we look at the needlework that women from Marash, Ourfa and Ayıntab, who survived the genocide and managed to go to Aleppo, brought with them, the differences between the needlework styles of 3 cities, the changes in those works in 100 years and the craft that mothers have been teaching to their daughters.

First of all, we would like to get to know you as an artist.

I was born in Gyumri. When my uncle Tigran Tokmakjian, one of the famous artists of Armenia, visited us in Gyumri, he said, “Tell me what you want me to draw.” Anything I want appeared on the paper in minutes and I was amazed by this. Taking my uncle's example, I had been wanting to became an artist since my childhood. My father was a botanist; I was saying that I want to be an artist and a botanist, because I didn't want to make him sad. When I was 15, we moved to Yerevan. I studied painting for 9 years: 4 years in Panos Terlemezyan Fine Arts School in Yerevan and 5 years in the university. I had many exhibitions in Syria, Lebanon and Armenia.

How much do you know about your family history?

My father's side is from Erzurum. They were engaged in smelting works. Between 1828 and 1830, during the migration from Erzurum to Russia, my family came to Armenia and they moved their craft to Gyumri. However, during Soviet Era, everything was produced in factories or imported. There was no production in Armenia. Having a shop was not common among craftsmen. My grandfather and his brothers carried out their smelting works until World War II though just barely, but after the war, they couldn't have continued.

How did you decide to go to Aleppo from Yerevan? Can you tell about the years you spent in there?

After I completed my university education, I worked as an art teacher in a village near Yerevan and then, I did designing works for a theater. In early '90s, Armenia was in a bleak condition. In 1992, AGBU related Martiros Saryan Academy in Aleppo invited me to work as an art teacher for 10 years. After 4 months, my wife and children also came to Aleppo. We were thinking that we will stay in Aleppo for 10 years, but we stayed there 23 years. Early years were tough. I was from a Soviet country. Not just the country, but also people were different. However, I got accustomed to the city in a short while. In our neighborhood, everybody was Armenian. The owners of the stores from which I had been shopping were Armenian. Still, I don't have good comprehension of Arabic. We didn't buy a house there, because we thought that we will go back to Armenia. However, we didn't think that the cause of our return will be war. I resisted for a long time, but I had no reason to stay left. In May, I left Aleppo with pain. When I arrived to Armenia, I felt like I returned to home. On the other hand, Armenia was also changed; many of my friends migrated to Russia or other countries.

As an Armenian from Gyumri, how was your relationship with Armenians in Aleppo?

Being from Gyumri has a positive effect on people. Since the Armenian spoken in Gyumri is close to Western Armenian, it was easy to talk to Armenians in Aleppo. Gyumri, second city of Armenia, is a city that preserves its traditions and produces art. And Aleppo is the second city of Syria and shares similar features with Gyumri. Armenians in Aleppo are tied to their traditions and appreciate art. I went to a second city from another second city.

What does losing Aleppo mean to you?

Aleppo was the last living piece of Western Armenia which we have also lost. The land wasn't ours, but Armenians from Cilicia were living there. When Aleppo was destroyed, for the world, a powerful city in terms of economy got lost. And for Armenians, the traditions and production of Western Armenians is destroyed. If I write my memoirs one day, I could say “I saw Western Armenians in their daily lives.” In big cities and countries, people lose their characteristics more easily. For instance, in Damascus or in Lebanon, life is fast and you can stand only if you are successful and you might not be able to send your child to an Armenian school, if you don't have money. On the other hand, in Aleppo, there is always a way. The solidarity among Armenians in Aleppo was very strong. There, Armenian was not a dead language that should be revived. There were literary magazines and textbooks in Armenian. In the periodicals, not only famous writers in Diaspora, but also students who write well were included; thus, new generations of writers and poets have been created.

How did you start to study on needlework? For instance, how did you come up with “Marash Needlework”, the first book of the series?

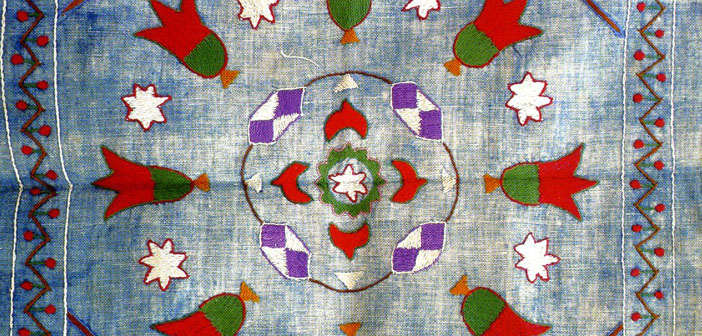

In 2007, with “Marash Armenians Foundation” in Aleppo, we wanted to remind and support the cultural production. 40-50 years ago, the best football team in Syria was the team of Marash Armenians. We interviewed with the players and complied those interviews in a book. People in Marash was very proud of their needlework and embroidery. I suggested an idea: “Why don't you prepare a book on Marash needlework?” Needlework of Cilician Armenian women has artistic value and serves for various purposes. In Marash, there are 2 types of needlework. One is plain embroidery, which people call “atlaslama” (“hartagar” in Armenian) and the other one is hidden embroidery called “irga” (“kağdnagar in Armenian). While atlaslama can be found in other provinces, hidden embroidery is peculiar to Marash region. Dark blue and red tones are widespread, which can be interpreted as a continuation of medieval tradition. Patterns symbolizing four elements and looking like cross are common. Marash had been an important center in terms of weaving and dyeing cotton. Fabric and string that is needed for needlework is produced from the local cotton. Almost everything, from carpets to nightgowns are made with cotton fabric. In Aleppo, the pieces that women brought from Marash were examples of traditional craft; their color and material were traditional. When they came to Aleppo, needlework went through some changes. Fabric, string and patterns have changed.

Which sources did you use during your research?

When I decided to do this, I wanted to read the entire literature on Armenian needlework. The library of Saryan Academy was very rich. I read the books on Marash. My main source was people from Marash. Most of the works in the book belong to Armenian women in Lebanon, Aleppo and Damascus. I visited them in their homes, listened to their stories and photographed the pieces that they brought from Marash and that they produced in Aleppo. Also, I put the examples from the museum collections into the book. Moreover, we put ads on periodicals and informed people in Lebanon and in the US. The people who have Ayıntab, Ourfa and Marash needlework photographed them and sent them to us.

Then, “Ourfa Needlework” was published. How did you prepare that book?

His Eminence Archbishop Şahan knew about the Marash book and he said that he want me to work on Ourfa. The first volume of needlework of women from Ourfo is published and I am still working on the second volume. When we look at Ourfa needlework, we can see that flower patterns are common. With simple and complex patterns, the needlework reflects the spirit of medieval paintings. There are twigs and a couple of flowers decorated with leaves in the pieces. Bent twig is a common pattern in western and eastern crafts.

What are the outstanding features of the needlework that were brought to Aleppo from Ayıntab?

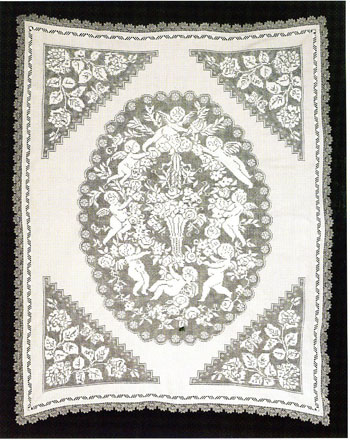

Collecting examples for Ayıntab book was the easiest part. There were a lot of sources. Ayıntab Armenians were damaged less in the genocide compared to other regions; so, they were able to take the old pictures, deeds, documents and fabrics with them. There were needlework in all Armenian houses in Aleppo. Main characteristics of Ayıntab needlework are sateen embroidery and lace. Embroidering similar patterns symmetrically is peculiar to Ayıntap needlework.

In Ayıntab lacework, we commonly see octangular stars. This is a symbol of His Eminence. Zeugma was one of the cities of Komagene Armenian Empire. Archaeologists are still carrying out excavations there. They found a mosaic that dates back to 1st century AD. I saw this mosaic in museum in Ayıntab. There was an octangular star on the mosaic. In 1914, Taniel Varujan was issuing an arts magazine called “Navasart”. There was an article in Navasart which is about the octangular star on a coin belonging to Armenian King Dikran Medz. I mean, the culture was a whole. We divide the history as before and after Christianity, but we see that the culture is undivided.

What do you want to say about the main differences in the embroideries of these cities and about the changes they went through in 100 years?

Marash Armenians were more provincial compared to Ayıntab Armenians. In Ayıntab, there was urban development. There is an American college in Ayıntab; so, the interaction with foreign countries is more intense. The embroidery is “more sophisticated”. There is a little bit of exaggeration too. There is embroidery on almost everything. They embroidered even the handkerchiefs. Both the nightgowns and the packages in which those gown are put are embroidered. It can be said that this is a result of a secure life. In Marash, however, they work on the pieces they would use and durability is valued.

Dates of Ayıntab works are more accurate. For other cities, there are approximate dates. They determine the dates from the dowries and the date of marriage of woman. However, the dowry might be transferred from mother to daughter. After Hamidian massacres in 1894-96, the missionaries came to the region and kept records; so, it is possible to determine the dates of the works that were done after the massacres. Fanny Shepard, an American missionary in Ayıntab, brought examples from the west, so that works of Armenian women can be sold in the western markets. Thus, there had been changes in the patterns until 1915. In Ayıntab, lacework is common and usually, there is an octangular star in the middle of the lace. With the western influence, angel patterns replaced the star patterns. In Ourfa, there were German missionaries. Contrary to Shephard, they encouraged people to preserve the traditional way. After 1915, embroideries changed with the migration. While women was working mostly with cotton fabric in Marash, they started to work with velvet fabric in Aleppo in '30s. Old craftwork had certain rules; you cannot change the colors. However, in new pieces, people use whichever color they want. There is meaning in the old works and the colors people used. Traditions are getting weaker. Now, we have been establishing schools in Armenia and teach needlework from the bottom up. However, needlework is a craft that is transferred from mother to daughter. The mother teaches the pattern and color.

How many people were left in Aleppo who are engaged in needlework?

In the recent years, there were a few people from Marash who are engaged in handcrafts. And they were doing little souvenir pieces. They wouldn't have done large bed covers, because that would take months and nobody pays for it. Older ones were partially-sighted. And there weren't more than 2 people who are engaged in Ourfa or Ayıntab needlework. Since Ayıntab needlework is more sophisticated and laborious, its price is 3 times more than Marash needlework.

Have you seen Marash, Ayıntab and Ourfa?

I didn't have time to wander in Ourfa. I visited many needlework shops in Marash. They showed me the pieces they have. I went to Ayıntap several times. We walked around Asdvadzadzin Church. I was impressed. In many cities of Turkey, people damage everything left from Armenians in order to wipe all the traces off. This wasn't the case in Ayıntab. Writings in Armenian on the windows of Nazaretyans' home were still there. We met Islamized Armenians. We talked to the copper-smiths. They said that they learned this craft from Armenian masters.

What is the importance of this book?

Some of the Eastern Armenians don't even know where Marash is. These books are important for understanding that Armenian people and culture is a whole. It is important for returning the culture to the people. Certain traditions are lost in time. At least the surviving traditions should be revealed. Armenian women are still engaged in needlework. When the Ourfa book was published, a designer friend used Ourfa needlework in the clothes she designed and made a fashion show. A person from Ayıntab who visited Yerevan took this book to Ayıntab.

What kind of difficulties you experienced, while you were preparing the books?

The most important aspects of the books is the scientific analysis of the needlework. Marash needlework is like painting; so it was easier to analyze them. However, when it comes to Ayıntab needlework, you have mostly lace and white; so it is harder to evaluate the patterns. Since analyzing the Ourfa needlework takes time, I still work on the second volume. For instance, there are flower bouquets, which is not common in traditional needlework. It is important to reveal these transformations and interactions.

“Some regions in Aleppo was like little Armenia...”

Though there have been migrations throughout the history, there has always been a settled Armenian population in Aleppo. Look at 500-years-old Manuk Church. On the other hand, Armenian population grew after the genocide. Most of the Armenians who came to Aleppo after 1915 were from Cilicia region. Ayıntab is only 150 kilometers away from Aleppo. Ayıntab Armenians managed to bring their belongings with them. Thus, there was no lack of sources in terms of Ayıntab. In the houses, there were a lot of handcraft works that date back to 19th century. Marash was affected from the genocide more compared to Ayıntab. The belongings they managed to save were fewer. There were many people from Ourfa living in Aleppo. After 15-20 years, Ourfa Armenians living in the villages under the control of France wanted to go to Aleppo. Until 1946, some regions in Aleppo was like little Armenia.