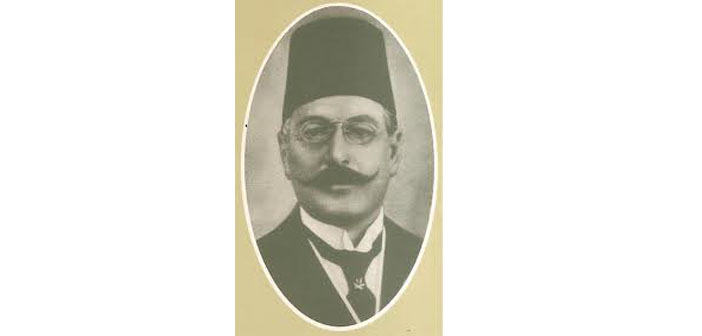

Diyarbekir celladı Doktor Reşid

1873’te Rusya’da doğan Mehmet Reşid Bey, gördükleri baskı nedeniyle 1874’te İstanbul’a kaçmak zorunda kalan Çerkes bir ailenin çocuğudur. Askeri Tıbbiye’de eğitim gördüğü sırada, 1889’da Osmanlı’nın bundan sonraki 30 yılına damgasını vuracak bir örgütün kurucularından olur. 2 Haziran günü, Tıbbiye’nin bahçesinde İshak Sükûti, İbrahim Temo ve Abdullah Cevdet’le birlikte kurdukları örgütün adı, İttihat ve Terakki Cemiyeti’dir (İTC).

Talat’ın gözdesi

Doktor olarak mezun olmasının ardından, İstanbul’da görev alan askeri doktor Düring Paşa’nın asistanı olarak atanır. Meşrutiyet coşkusuyla doktorluktan istifa ederek Trablus’tan İstanbul’a dönen Mehmet Reşid, artık bir bürokrattır. Yöneticilik kariyeri İstanköy’le başlar, Lübnan’la devam eder. 1913’te, âdeta Ermeni Soykırımı sırasındaki uygulamalarının staj alanı olacak Karesi’ye mutasarrıf olarak atanır. Rumların bölgeden zorla gönderilmesinde önemli bir role sahip olan Reşid Bey’in bu ‘başarı’sı, ona, Van, Bitlis, Diyarbekir ve Mamuretülaziz vilayetlerini kapsayan Umum Müfettişliği’nin Kâtib-i Umumiliği unvanını getirir. Dâhiliye Nazırı Talat Paşa, onu “faal, muktedir ve erbab-ı hamiyetten gördüğü” için, bu görevi Reşid’e vermiştir.

‘Nazik bir zaman’

25 Mart 1915’te Diyarbekir Valisi olarak atanan Reşid Bey’in şehre geldiği dönem, kendi deyimiyle “harbin en nazik bir zamanına tesadüf etmiştir.” Reşid’in bu dönemi atlatma planlarından biri de “saldırgan tutumlarıyla hükümetin şerefini zedeleyen Ermenilerin meselesini halletmek”tir. Zira, Diyarbekir’dan önceki görev yeri Musul’dan Diyarbakır’a doğru yola çıkarken, Talat Paşa’ya yazdığı telgrafta şunları yazar: “Bu sırada ne yapılırsa kâr sayılacağından Ermenilere karşı en kestirme usulü tatbik etmek fikrindeyim.”

Şehre adım atar atmaz, şehirde saklanan asker kaçakları, geniş bir tahkikat başlatır. Şehrin tüm Ermeni ileri gelenlerini tutuklatır. Tutuklananlar, ayaklanma planlarını itiraf etmeleri için işkenceden geçirilir ve öldürülür. Mayıs sonunda Talat Paşa’ya gönderdiği telgrafta, “Ermenilerin Musul ve Cizre’ye sürülmeleri gerektiğini” yazar.

Sürgün güzergâhındaki ahalinin Ermenilere karşı kışkırtılmasını sağlayan Reşid, şehirdeki Ermeniler için hazırladığı sonu, Ramanlı Mustafa’ya şöyle anlatır: “Bak Ağa! Burada çok zengin Ermeniler var. Sen, kardeşin Ömer ve adamların kelek tedarik edeceksiniz. Ben sizlere kâfile kâfile Ermeni teslim edeceğim. Şayet sizlere sorarlarsa, ‘Sizleri Musul’a götürüyoruz’ diyeceksiniz... Onları kelekle Dicle üzerinden götüreceksiniz. Kimsenin göremeyeceği bir yere varınca, hepsini öldürüp Dicle’ye atacaksınız... Ne kadar malları varsa adamlarınıza. Ne kadar altın, para ve mücevherat varsa onların yarısı sizin, diğer yarısını da

Hilal-i Ahmer’e (Kızılay’a) vermek üzere bana getireceksiniz.”

Böylece 1914’te atandığı Diyarbekir’de bulunan 56 bini aşkın Ermeni nüfusu, 1917’de 1849’a düşecektir. Reşid Bey, tehcir güzergâhı üzerinde bulunan Diyarbekir’e gelen Ermenilerle birlikte, vali olduğu dönemde vilayette bulunan Hıristiyanların yaklaşık yüzde 90’ını yok etmiş olacaktı. Reşid’in kurbanları, Hıristiyanlarla da sınırlı değildir. Tehcir emrine karşı gelen Lice Kaymakamı Nesimi Bey’i de Diyarbekir’i çağırtır ve yolda onun da ölüm emrini verir.

Daha sonra Ankara’ya atanacak olan Reşid’in, Ermenilerden kalan mülkleri usulsüzce zimmetine geçirmesi, Talat Paşa’yı bile kızdıracak ve görevinden azledilecektir. Haçig Fardjalian’ın aktardığına göre, Diyarbekir’de elde ettiği bu zenginlikten 43 kutu mücevheri, yanında Ankara’ya götürür.

İntihar etti

Kasım 1918’de, soykırım faili olarak Bekir Ağa Bölüğü’ndeki yerini alacaktır. Ocak 1919’da buradan kaçmayı başaracak, fakat yakalandığında idam edileceği korkusuyla intihar edecektir. Ardında, 1917’de Mithat Şükrü Bey’in soykırım sürecinde bir hekim olarak nasıl bunları yaptığını sorduğu soruya, 1915’te yaşattığı vahşeti net bir şekilde anlatan şu cevabı bırakacaktır: “(...) Ermeni eşkıyası, bu vatanın bünyesine musallat olmuş birtakım zararlı mikroplardı. Hekimin vazifesi de mikropları öldürmek değil midir?”

Fakat Cumhuriyet rejimi, onu suçlarıyla değil, iftiharla anacaktır. 1922’de yılında TBMM tarafından “şehit-i milli” ilan edilirken, ailesine Ermenilerden kalan dükkân ve evler verilecekti.

Kaynaklar: Ayhan Aktar, ‘Diyarbakır 1915: Kötülüğün arkeolojisi’, Taraf, 1 Şubat 2012; Hans-Lukas Kieser, ‘From ‘Patriotism’ to Mass Murder: Dr. Mehmed Reşid (1873-1919)’, ‘A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire’, 2011; Uğur Üngör, ‘The Making of Modern Turkey: Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1950’, 2011.