Entrusted to her daughter fifty years after she was abducted, the memoirs of Gülizar have been published in Turkish by the Aras Publishing House with the title ‘Gülizar’s Black Wedding’. Gülizar’s story contains messages for us all…

Rigid accounts of official discourse often leave their imprint on the most troubled periods in history. These denial-based narratives mostly focus on concealing the truth and finding pretexts for acts of persecution, yet the truth that lies beyond them is revealed by witness accounts and stories of real people. The environment of disquiet and fear that began for the Armenian people in the years 1877-78 when the Ottoman-Russian war broke out, and rumours of independence and loss of land began to spread simultaneously, and the goading of the Kurdish tribes by the Istanbul government in order to control eastern regions, is a period of time overlooked by the official narrative of history in the course of events leading up to 1915. Now we have the opportunity to read and understand this period via the life story of an extraordinary woman for whom laments have been composed. Written by her daughter Armenuhi Kevonyan, Gülizar’s story holds the record of the history of an entire society in the person of a fourteen-year-old young girl abducted by the most fearsome figure in the region, Kurdish tribe leader Musa Bey

Fear is among the most powerful human emotions, and its interpretation is often trapped between the opposite poles of cowardliness and bravery. Yet courage is not the absence of fear. Courage is having no other way but to act despite your fear, or in other words, exhausting all your fears. Gülizar was so, a person who had been inundated with, and exhausted all her fears.

The most beautiful daughter of the family, Gülizar was born in Muş as a grandchild of Miro (Mihran), the leader of the Khars village. However, she was abducted by Musa Bey, the person her family had sought to flee by seeking shelter in Muş. Musa Bey had seen Gülizar at a wedding, and overcome with the resentment of rejection, had added the name of Miro to the list of those who transmitted the complaints of the local folk about him to Bitlis Governor Edhem Pasha. Revenge came at one of the most vulnerable hours on the night of Easter Monday. Musa Bey lay siege on Miro’s home with 150 men, and abducted Gülizar.

Might of resistance borne of disaster

This was not the first or the last act of persecution. The fate of the abducted girls and women would often be decided within a framework of death or submission. What renders Gülizar’s story unique is her determination to transform this disaster into a struggle of power. Taken to Musa Bey’s home in the Hevedig village, Gülizar was deemed appropriate to be given to Cezahir, Musa Bey’s younger brother, since Musa Bey already had four wives. Her new name became Fatma, and she was sentenced to a life where she would live whatever she was allowed to. Or so they thought.

At every opportunity, Gülizar tried to send messages to her family, and she protected her religion, language, name, Armenian identity and her past, or in brief, her existence, from which she derived great might. However, it is in the nature of persecution to be honed in the face of resistance. In an environment where humiliation, beatings and threats are considered natural parts of everyday life, in order to understand the scale of Musa Bey’s cruelty, it is sufficient to hear the cries of her family, who at first were delighted to hear she was alive, but exclaimed when they found who was holding her: “We wish death had taken our daughter, rather than hearing news that she was in Musa Bey’s hands!”

The court process meant Gülizar had to simultaneously experience the cautious stance of institutions such as the Patriarchate and the Armenian National Assembly, and Khırimyan Hayrig, the most influential religious figure of the period, taking her under his wings. In a sense, Gülizar had become a mirror in which everyone saw his or her own truth reflected

A test at court

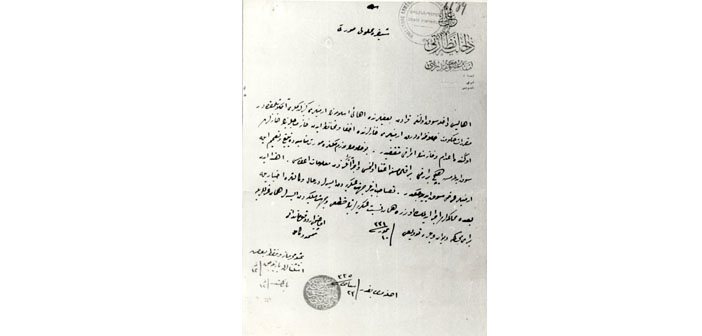

As a result of her family’s efforts, the Sultan ordered the Bitlis Governor to be summoned to court to testify on whether she is Kurdish or Armenian. When the day of the arduous test came, Gülizar ran to her mother’s arms, shouting, “Mercy! Mother! I am an Armenian, and I will die as an Armenian!” and she tore the clothes she had been forced to wear apart, remaining half naked in her undergarment. This was what she said: “I want to return to my father’s home, to the way I was before I was abducted by Kurds.”

The court process meant Gülizar had to simultaneously experience the cautious stance of institutions such as the Patriarchate and the Armenian National Assembly, and Khırimyan Hayrig, the most influential religious figure of the period, taking her under his wings. In a sense, Gülizar had become a mirror in which everyone saw his or her own truth reflected.

Resistance until her last breath

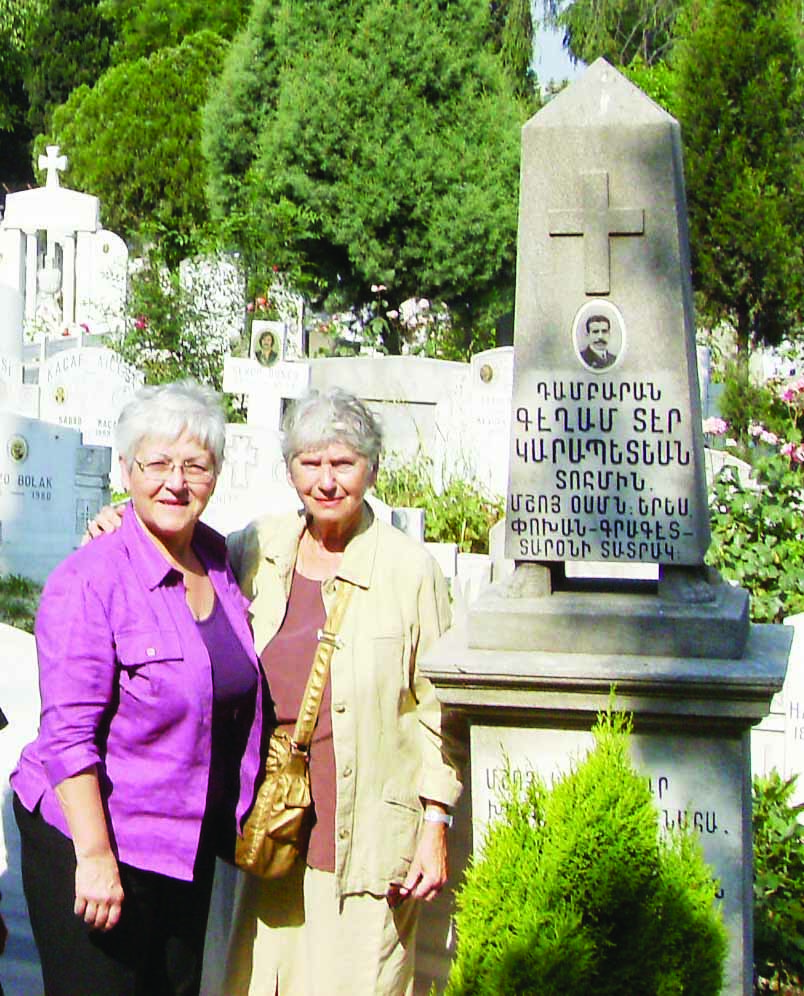

Gülizar married Keğam Der Garabedyan, the Secretary of the Muş Armenian Bishopric, priest, Muş-Bitlis Armenian Member of Parliament and administrator of the Tashnak organisation. The remaining years of her life is also a story of resistance against persecution, since the State’s policy of destruction did not change. So much so that, Musa Bey would be acquitted of all charges, then upon appeal would be exiled to Mecca, yet a year later would be appointed as the head of the Hamidiye Corps by Sultan Abdul Hamid II. Then came the inferno of 1915.

Gülizar yearned for her homeland until her last breath, and transforming her death into an act of resistance, she speaks to us: “Keğam died in Istanbul, an alien land to him, with yearning for his homeland Muş in his heart, whereas I live on without consolation. I believe in miracles. I will continue to resist until the day comes when I can take Keğam’s remains with me to our homeland so we can become one with the holy land together.”

Keğam Kevonyan, one of Gülizar’s grandchildren who has contributed an article to ‘Gülizar’s Black Wedding’ describes the feeling of absence transmitted from one generation to the next, and the struggle against it with the following words: “Gülizar, the villagers and hajjis of Muş, missionaries at the school, freedom fighters, they have all passed away. The stones, too, have died; the mountains, planes and rivers, too. They all died, with a beautiful or tragic death, and some died while they were still alive. But their faith did not died, because it did not have the time to be realized, and it lives on in us now. All our dead that continue to live on within us shape our spirit and will, orient our thoughts, and draws the line of our fate…”

Keğam Kevonyan’s final call may be deemed a last will: “Until the innocent can reach their graves, until truth finds its path, our mission will not end, and the eye fixed on Cain’s neck will remain wide open.”

On the path to attain that truth, may Gülizar’s story bestow inspiration, will and faith to all.