An Anatomy of Privilege: Being an Armenian from Istanbul

TALİN SUCİYAN

Being born in the capital of an empire inherently involves a dimension closely tied to violence and coercion that is often carefully hidden. No one arrives in the capital of an empire casually; either you must be highly privileged—having lived generations in superiority, which inevitably includes exerting force over others—or you must have come, or been brought, out of necessity. The prestige of being in the imperial capital overshadows the narrative of how one arrived or stayed there, instantly marking that person with remarkable privilege.

The primary reason for this lies in the fact that the capitals of empires have always been more privileged than other regions, serving as centers of capitalist economies and power. Consequently, sharing the same air as those in power becomes a source of prestige, distributed almost universally to the city’s residents, whether rich or poor. You might not have a prestigious job; you might even be unemployed, powerless, and completely irresponsible—but you’re from Istanbul.

The arrival of Armenians in Istanbul, whether during the Byzantine or Ottoman periods, occurred through the will of those who held power at the center. Armenians fleeing westward during the Celali rebellions settled near Istanbul, but the city did not easily open its doors. In the 19th century, Armenian men from the provinces (referred to as kawaratsi, living in places outside Istanbul, particularly in the eastern provinces or their yergir, homeland) were able to come to the capital—as cheap day laborers, porters, or bakers. In the 20th century, after successive disasters, Istanbul opened its doors to women and orphans who had survived massacres and deportations, granting them refuge in what was once known as Der Saadet (Gate to Bliss).

Coming to Istanbul came at a cost, especially for Armenians from the provinces. In 1966, when Armenians migrated en masse from Varto, the event made headlines in Turkish newspapers. The migration was linked to the Varto earthquake, legitimizing their arrival in the eyes of those in power. After 1915, Armenians were no longer wanted on their historical lands, yet they were not openly allowed to leave for other places. Subject to attacks, forced to sell their properties for next to nothing, fearing the abduction of their daughters, and, if Islamized and displaced to other provinces, dreading the discovery of their Armenian identity—they would secretly flee to Istanbul under the cover of night. Coming to Istanbul became synonymous with dispossession, landlessness, dispersion, poverty, deprivation, and the experience of diaspora.

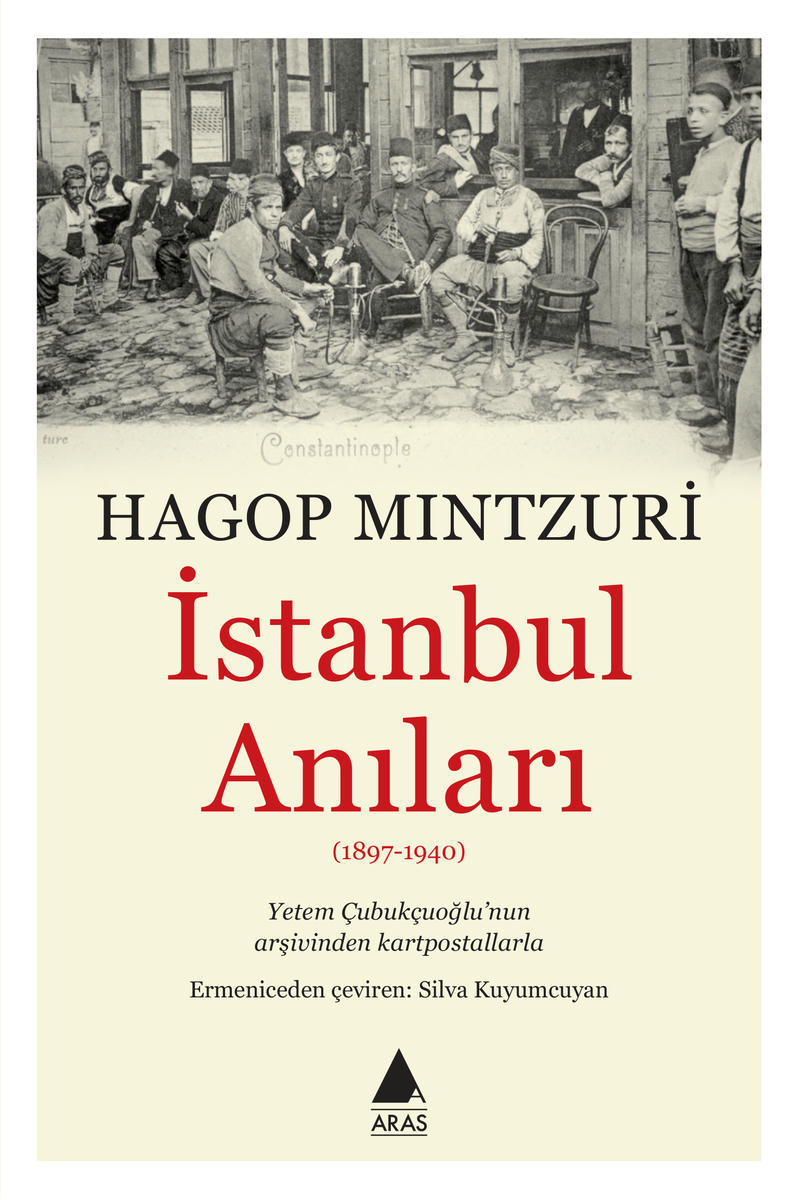

Hagop Mıntzuri, one of the most prolific Armenian writers of the 20th century, came to Istanbul for a tonsillectomy but stayed after the declaration of military mobilization, losing his entire family back in the provinces. Being in Istanbul saved his life but separated him from everyone who had given meaning to his existence. Later, Mıntzuri described living in Istanbul as a form of captivity. In his lesser-known yet significant novella Second Marriage (1931), which bears witness to an important but little-known period, Mıntzuri critiques the apathy, lack of justice, arrogance, and indifference of Istanbul Armenians, who seemed preoccupied with trivialities while looking down on Armenians from the provinces. Through this, he offers the perspective of a provincial Armenian writer on what it means to be an Istanbul Armenian.

History books almost never depict Istanbul as the capital of survivors after 1915. Yet until the 1940s, Istanbul was home to countless kaghtagans (perpetual exiles) and kaghtagayans (the centers where they found shelter in Istanbul). Afterward, Istanbul became a city where kaghtagan families were forcibly assimilated into being Istanbulites, with those who could leave heading to Europe or the United States—a city in constant flux, both receiving and sending migrants.

True to its imperial grandeur, Istanbul has always been a capital of institutions, not roots, for Armenians. This rootlessness was compensated for by the strength of institutions, which, through figures like the amiras, Armenian architects, writers, and artists, upheld a superior, privileged Armenian identity. After 1923, the Treaty of Lausanne reaffirmed Istanbul’s privileged status in practice, establishing the city as the core of Armenian institutional life, creating the illusion that no Armenian community, church, monastery, or administrative structure existed anywhere else in Turkey.

The erasure of the provinces (kawar) in the 20th century also meant the loss of critical voices from those regions. The critical gaze on the social and institutional life of Istanbul Armenians was left to a small, mostly male, group. The Armenians from the provinces who managed to survive in Istanbul became the new privileged elite within this rootless yet institutionally robust society. They were the new Istanbul Armenians.