A political prisoner Armenian woman in an Ottoman prison

It is difficult to find a prison testimony at the late Ottoman Empire, and it is unlikely that it was written by a woman. Also, the fact that this woman is Armenian makes Vartuhi Kalantar's memories of the General Prison, recorded as the first modern prison of the empire, very valuable. This memoir of Kalantar was published in Armenian by Aras Publishing in 2022 under the name "Hapishane-i Umumi Women's Ward, 1920-1921", and was recently published in Turkish with the translation of Artun Gebenlioğlu.

Vartuhi Kalantar, who stayed in the General Prison from June 1915 to 1918, was a political prisoner. The dates 1920 and 1921 in the memoir take us to the Hay gin magazine, where it was first published under the name "Getronagan pandin gineru pajinı" (Hapishane-i Umumi Women's Ward). It was thanks to Lerna Ekmekçioğlu that it escaped its waiting in the archives and reached today's readers. Ekmekçioğlu, who is McMillan-Stewart Associate Professor of History and Head of the Department of Women and Gender Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, first came across an announcement in Haygin magazine in 2005, during her thesis study. This is an announcement from 1920 that Vartuhi Kalantar's prison memoirs will soon be published serially. Of course, it surprises and excites Ekmekçioğlu that an Armenian woman recorded her two and a half year imprisonment in this way.

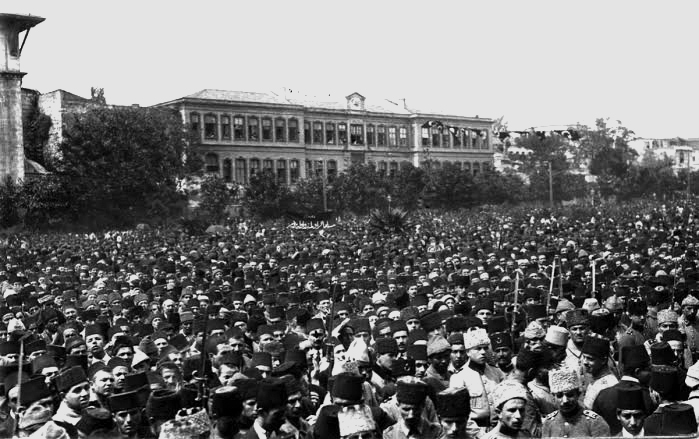

General Prison in 1920's

General Prison in 1920'sIn the light of what we know so far, this book can be described as "the first prison memoir written by a woman in the Ottoman Empire". In her foreword, Lerna Ekmekçioğlu also states that it is generally the first prison memoir written by a woman in the Middle East. So who was Vartuhi Kalantar? What caused her to be tried in the Martial Court and imprisoned in the General Prison?

A 20-year-old woman wanted to be executed

Vartuhi Kalantar was born in Bursa in 1895. Her family moved to Istanbul in 1908. Her father, Tavit Kalantaryan studied philosophy and pedagogy and then taught in Armenian schools. He established the Kalantaryan School, the first mixed school for Ottoman Armenians. This was a school that was considered "feminist" by its contemporaries. Likewise, Vartuhi's mother, Takuhi Kalantaryan, was also an educator.

When she was 16, Vartuhi went to Lausanne to study literature and history. The Armenian students and some political figures she met there helped her to shape his political thought and to sharpen her revolutionary ideas leading to independence. After a period in Lausanne, she moved to the University of Leipzig to study ancient history and pedagogy. When the First World War started, she did not want to leave her family alone and extended her visit to Istanbul for summer vacation and. In May 1915, upon a tip-off citing some of Vartuhi's letters and political activities, their house was raided and she was arrested along with his father, who was in his seventies, for "separatism". The place where they were brought was the General Prison, where the Armenian intellectuals gathered from their homes on April 24, 1915 were also kept. This first "modern" prison, opened in Sultanahmet in 1871, is also known as Mehterhane. (The book also includes an article on the General Prison, written by İzzet Umut Çelik, who works especially in the field of prison history.)

In order to accompany her 20-year-old daughter in this process, her mother found a way to have herself arrested. We read from her memoirs, published as a sixteen-issue serial, that her mother was also with her. Months later, when they were tried as a family, due to some diplomatic interventions and the efforts of some figures such as Zabel Yesayan, the verdict was not in favor of the death penalty requested by the prosecutor, and Vartuhi and her father were sentenced to five years in prison. Mother Takuhi was acquitted. The fact that the family was originally from Russian Armenians allowed them to be released after two and a half years, instead of serving the full five years, thanks to the article for prisoners of war in the Treaty of Brest Litovsk.

A mademoiselle among the lice

Kalantar cleared the notes she kept while in prison after she was released. Apparently she has more records of the early years. Translating the notes into text later allowed her, as a political woman, to describe the power relations in the prison and some figures based on observations over a long period of time. She is a good observer and a woman who uses language skillfully; she has subtle observations and very impressive expressions while conveying them. Sometimes it's almost poetic, sometimes it's powerful because of the emotional intensity of what happened. Although it is not very long in volume, what we have here is a truly special, rare and even unique memoir.

Especially what was done to her father and of course her mother makes her very angry and sometimes this can lead to a very harsh and even superior view. Being one of the few Armenians in the women's ward and being tried with death penalty while the First World War and the genocide were going on is not an easy thing, and it is necessary to read it from this perspective. Lepers' Room, Gentlemen's Room, evening entertainment; Kurdish Sinem, Persian Atiye, Arabic Fatma, Janitor Mustafa, guards, rangers... A "mademoiselle" in pedicular’s ward. Perhaps the prison doctor, the only figure she remembers well, helped her to maintain her sanity. Thanks to a translation work she made from German, she had the chance to get away from the ward from time to time and, as a kind of reward, to see her father from time to time.

After her liberation and a year after she lost her mother in 1921, Vartuhi Kalantar settled in America and wrote many articles in Armenian and English, mainly on politics and history, until her death in 1978.

She married to Zaven Nalbantyan, who was originally from Antakya, in 1923. There are also articles she and her husband wrote with the signature "Zarevand". Although the pseudonym Zarevand is identified with Nalbantyan today, there is also Vartuhi Kalantar behind it.