This is not a classic family history search story. Uskan investigates her grandmother, who passed away when Uskan was 16, and whose Armenian identity she knew nothing about because grandmother kept it a secret, and of course her mother Maria, in her village, through official documents and possible church records. This is a search that considers it natural not to find anything because it Uskan aware of what has happened. She wanders through the narrow streets of Adana, the dilapidated corridors of the Apkarian School, and the wild nature of the countryside, turning the camera into a hand that touches the present.

I wonder what these lands looked like during the Ice Age, what kind of creatures were roaming around, what kind of storms were breaking out then? I will talk about a documentary. No, it's not about the history of the world or humans on this planet, but the subject first appears in my mind with a giant hole from the Ice Age.

The reason why it was named Dipsiz (Bottomless) Lake must be due to its history dating back 12 thousand years to the last stages of the Ice Age when the human species was growing up; maybe it is not known where the bottom actually reaches. In 2020 AD, some people applied to the relevant authorities to excavate this lake in Taşköprü Plateau, fifty kilometers away from Gümüşhane.

Because of the rumors that there was treasure at the bottom of the lake, no one wondered what could be searched for in this glacial lake at an altitude of over two thousand meters, and permission was granted. It's unbelievable, but in this country, all the water of a lake was drained under the supervision of the gendarmerie for the sake of treasure. No one was held off the excavation site; indeed, at that time, titles in Ekşi Sözlük such as "Destruction of Dipsiz Lake with the permission of the governorship" and "Filling water into Dipsiz Lake with tankers" were blocked by court order.

The bottom of the Dipsiz Lake was dredged; Armenian and Greek treasures were searched for four days in the mud. It was bottomless, nothing came out. Respect for the lake, as well as for people, was lacking. When the work was completed, the lake was filled with water by tankers so that it could return to its former state. But the lake was a living thing, and when it was treated like a pool, it got angry, its color became blurred, and the life in it ended. The lake died because of treasure delusions. The natural allegory of truth leaves no further words.

Horizontal and vertical pursuits

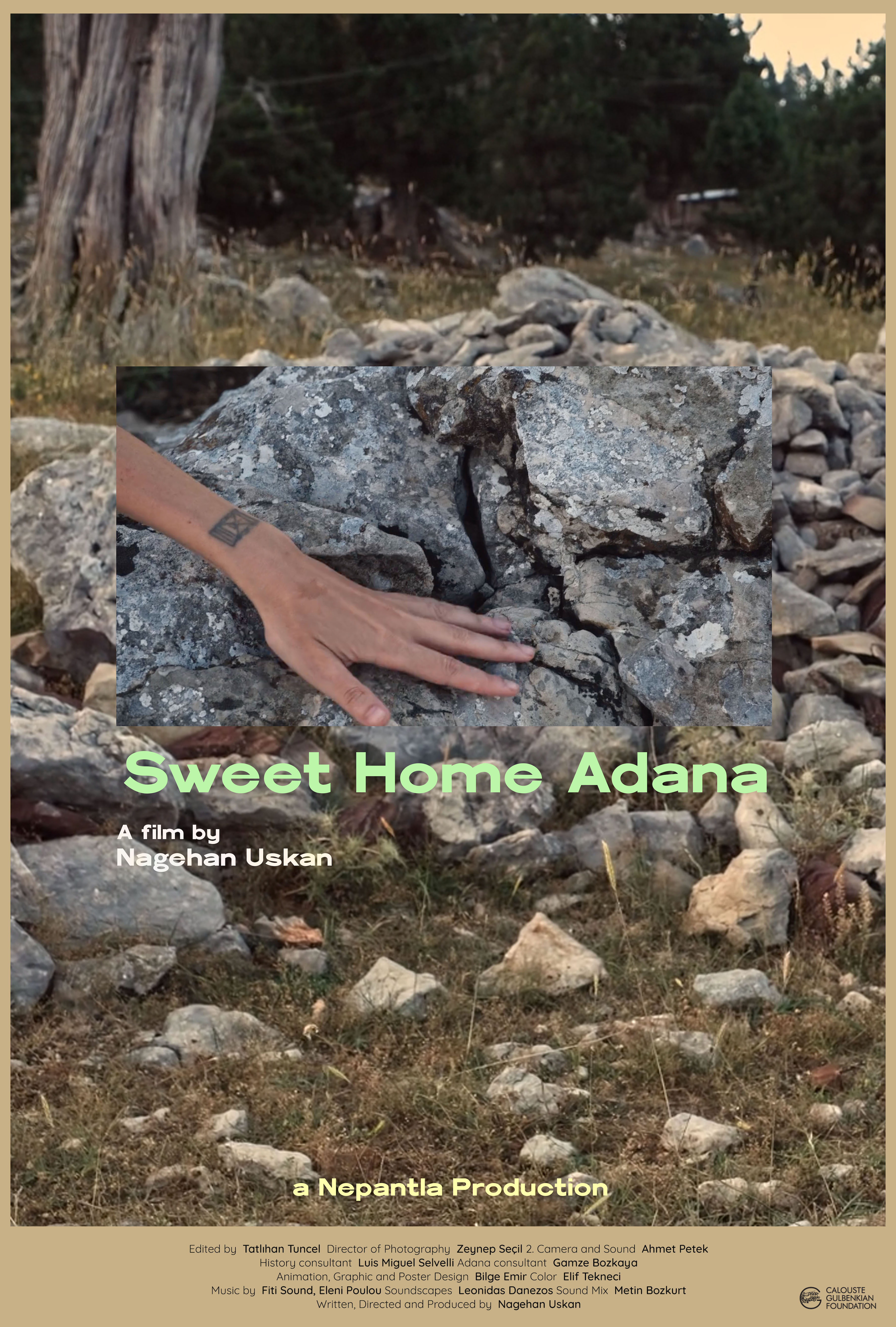

"My grandmother would run her hands slowly over the surface to find something that had fallen and disappeared. She groped by touching what the eye could not see." The film opens with the voice of director Nagehan Uskan. "Sweet Home Adana", which was awarded the Johan van der Keuken New Talent Award at the 17th Documentarist Istanbul Documentary Days, is the product of this need to wander slowly in search of what is lost today. In this twenty-minute documentary, Uskan, who has previously worked as a producer, sets out on a seemingly personal quest in search of her grandmother and her mother's Armenian roots in Adana.

This is not a classic family history search story. Uskan investigates her grandmother, who passed away when Uskan was 16, and whose Armenian identity she knew nothing about because grandmother kept it a secret, and of course her mother Maria, in her village, through official documents and possible church records. This is a search that considers it natural not to find anything because it Uskan aware of what has happened. She wanders through the narrow streets of Adana, the dilapidated corridors of the Apkarian School, and the wild nature of the countryside, turning the camera into a hand that touches the present. We are trying to visualize the life of Maria, a healer who made medicine from plants, as Melek, with what we know about the Adana Massacre and the Islamized Armenians. What is passed down to his daughter one generation later is a closed book.

Parallel to this flow, Uskan includes images shared by treasure hunters in public spaces of the internet such as YouTube. Sad images of those who "search" the same land for a completely different reason, raw because they do not hide their intentions, sad because massacres can only be carried to the present day in the hope of treasure, not reckoning. Their excitement and eagerness irritates people, and even turns into a bad comedy. Some of the posts are so ridiculous that Uskan says that she couldn't use every image in order to prevent the movie from drifting into such a tone. For example, "When you say Armenian, cryptic signs come to mind. Arrows and triangles are things they will not give up," says someone for sharing their "experience". They are some people who missed the times when the bricks and mortars of non-Muslims was plundered, but now want their share of this dark share-out and are angry when they cannot reach it.

During a field research in Adana, Nagehan Uskan came across treasure pits near Armenian sites of memory and started photographing them. "I thought that these were shame on the one hand and a completely different dimension of denial on the other. When I looked at the videos that the treasure diggers uploaded to YouTube, their conversations among themselves, sometimes talking to rocks and stones, their stubbornness, their reckless destruction and their boastful display of it, they contained many meanings together. There was a vertical search that went parallel to my horizontal search. That's why they became a dialectical and indispensable part of the movie," she says of the treasure hunters who, like her, focus on rocks and stones.

Searching among the ruins

Another wall which the film leans against is "Yıkıntılar Aarasında (Among the Ruins)", in which Zabel Yesayan shares her impressions of the 1909 Adana Massacre. Uskan says that her admiration for Yesayan is not directly linked to her own roots:

“This issue is completely political for me, my personal story is maybe just a pretext to tell it. I was sure that I would not be able to find the roots before starting this journey. The archives in Nantes gave me a hope for a moment that I did not expect, but when I could not find it, I was not surprised, nor was I greatly disappointed. Because we know more or less how the country we live in approaches history. My main concern was to reveal in different ways the dimensions of the forgetting, washing away and destruction mechanisms behind this obscurity. On the other hand, the disintegration of the memory from the past and that destruction still continues. While wandering among the ruins, despite all this, the important thing was to still be able to see that memory, the Armenian memory, in a lively and green house.”

At the first screening of “Sweet Home Adana” at Documentarist, Kayuş Çalıkman Gavrilof, who is the translator of “Yıkıntılar Arasında” and appeared in the documentary with pieces she recited in Armenian from Yesayan, was also present. She told a story that day, which is not only example. Maybe we can add this story to the end of the documentary that continues in life: Because of being Armenian and a translator, she had some messages from some Turks she knew: "I'll send you a picture now, what's written there?" She says “this is definitely a treasure rumor. I have personally witnessed this, it is very common in the forums that bring treasure hunters together on the internet, they make such plans when they find a map or a document. They say, ‘What, we can find an Armenian and have him translated, it’s not a big deal?’” The landscape is sad, the pit is bottomless.