Survival as a work of art

TALİN SUCİYAN

“Every Armenian is a document,” said Hrant Dink. We are going through a new era where Armenians are trying to understand what happened to them through their personal and family histories, as well as their own experiences. The nature of this time requires us to see the survivors' struggle for survival, to respect them, to honor them, to give them the place in our lives that they deserve. It could be said that more and more Armenians are focusing on their own family history and the catastrophic experiences of their grandparents as a way of approaching the catastrophe and confronting their part of it by engaging with creative productions. In this way, the Armenian struggle for survival is reflected in the practices of art, which evolves from mere documentation to art.

Long before 1915, Armenians had begun migrating to the United States due to abusive taxation and other oppressive policies in the provinces. The best known of these migration centers is Fresno, the hometown of William Saroyan. Another, of course, is Philadelphia. Armenian families in Philadelphia, which is still a heavily Armenian-populated city today, have numerous correspondence with their relatives living in the Ottoman provinces, photographs, and family archives documenting the daily life of Armenians at the turn of the 20th century. The widening of the field of historiography with the inclusion of survivor experiences from biographical and autobiographical accounts makes new ways of approaching the catastrophe visible.

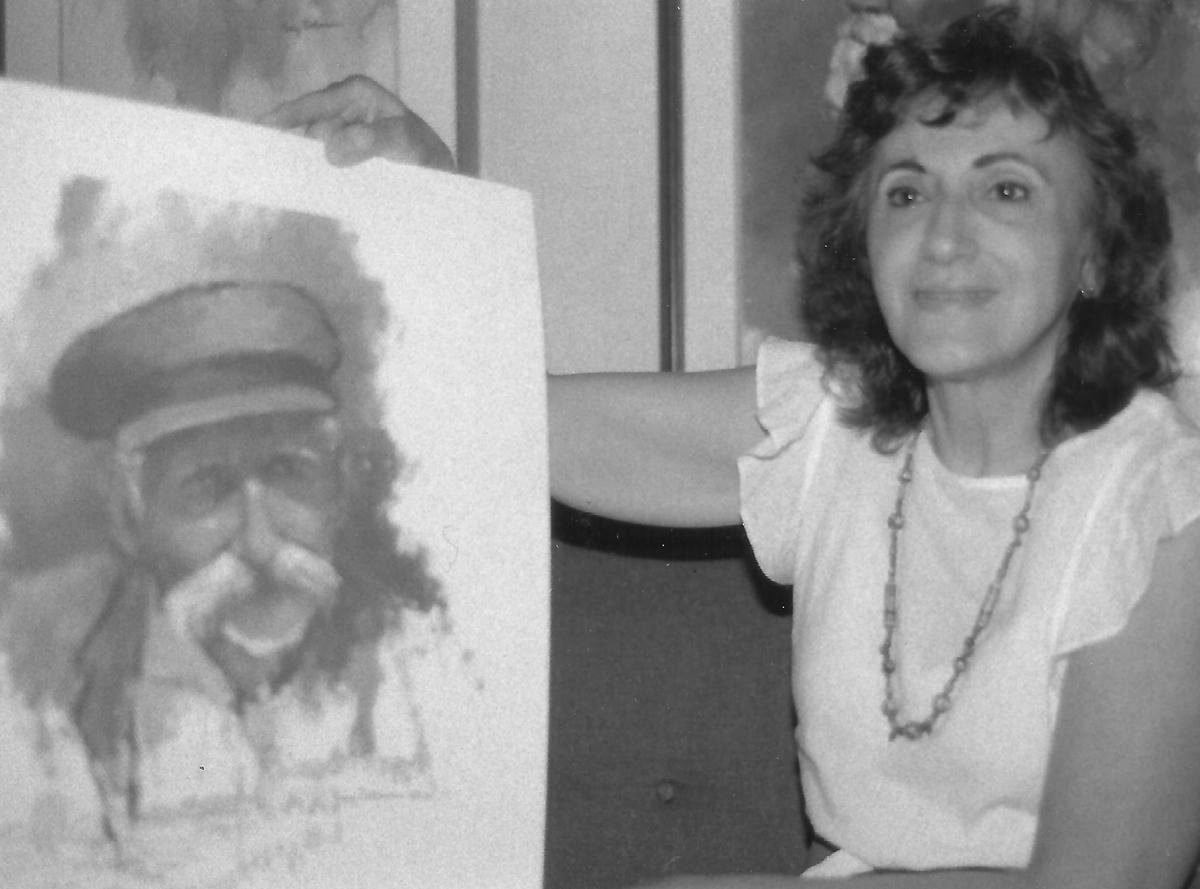

Mary Zakarian with Face of Freedom

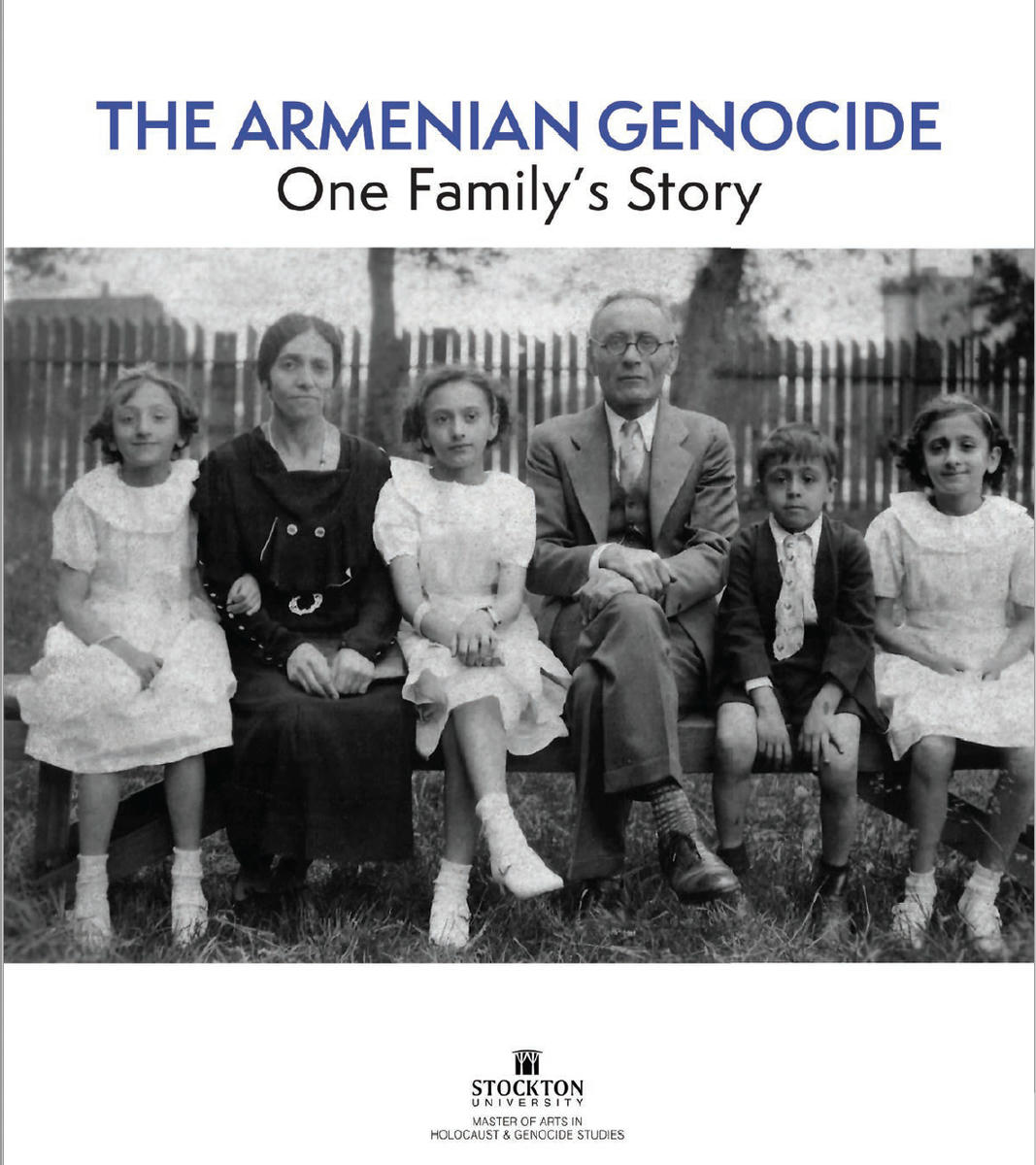

Mary Zakarian with Face of FreedomThe exhibit “The Armenian Genocide, One Family's Story”, organized last year at Stockton and Montclair universities, was a good example of this. The exhibition tells the story of the Zakarian and Arpajian families from Hınıs and their experiences of survival and building new lives. In this way, we also have the opportunity to learn the story of Armenian American painter Mary Zakarian. Mary Zakarian's mother Arek (b.1895) and father Movses (b.1881) were survivors who lost their families in 1915. Arek had been married before; after losing her entire family, she worked as a servant, first for a Muslim family and then for an Armenian family in Istanbul. Then, like many other young Armenian women, constant exile brought her to the United States. Movses Zakarian, a prominent duduk player, went to the US in 1913 and never saw his family he had left behind in Hınıs. Both Arek's and Movses' experiences are not limited to their own families. Today, every Armenian family living in the US or anywhere else in the world has a similar or even identical history. This commonality is important as it reminds us that family histories are not singular or individual, but a reflection of a collective history.

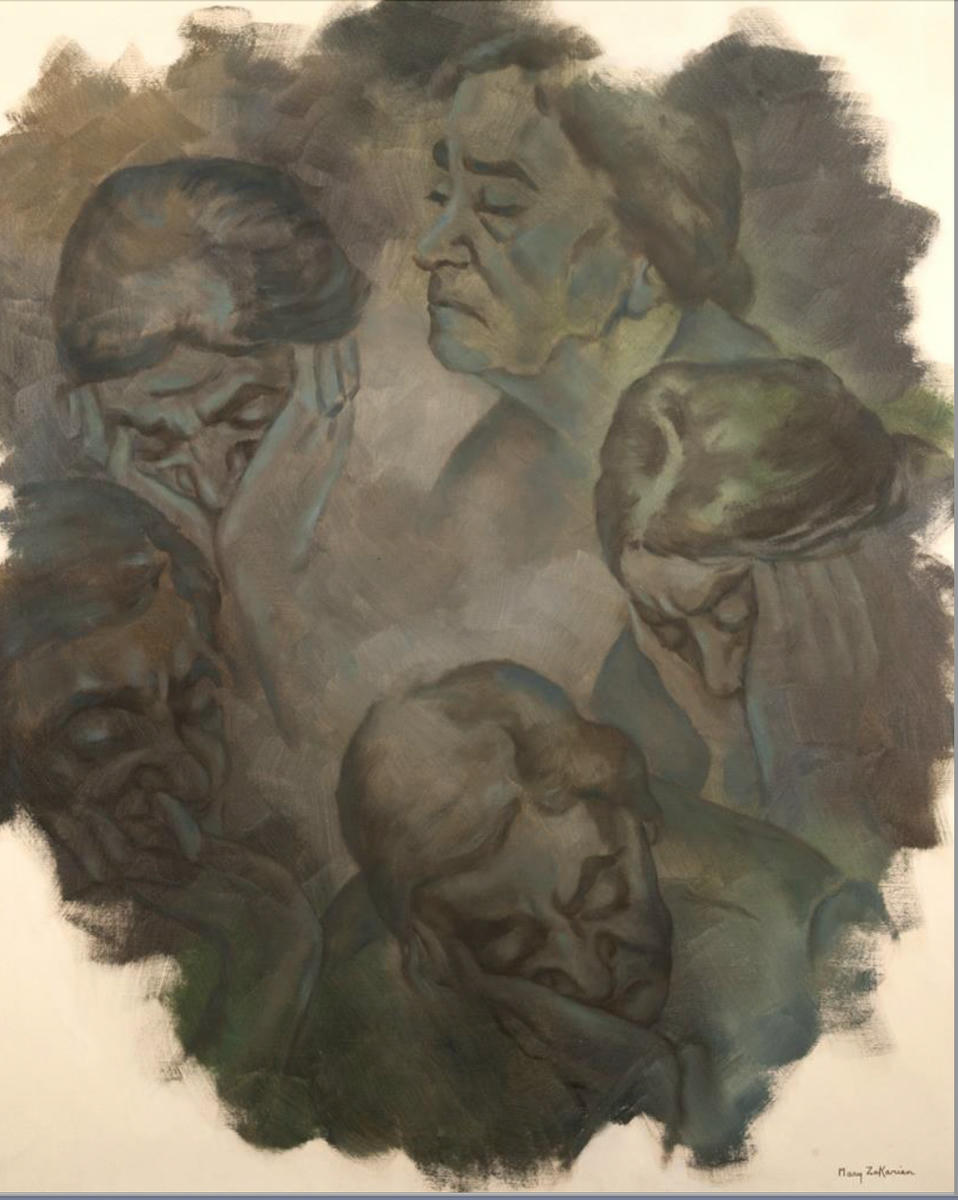

My Mothers Endless Lament

My Mothers Endless LamentMary Zakarian, one of the four children of Arek and Movses Zakarian's family in the new country, spent her entire career as a painter painting the reflections of the catastrophe on her own family. 'My Mother's Endless Lament', exhibited in 1974, is one of her most important works. In 1971, he founded the Zakarian School of Art, where he trained hundreds of artists.

Grandchildren Susan Arpajian Jolley and Alan Arpajian have been active in the preparation of the exhibition that tells the history of the Zakarian family, bringing together family photographs and letters. The Arpajians are also the authors of 'Out of My Great Sorrows: The Armenian Genocide and Artist Mary Zakarian' (2107, Routledge Publishing).

As the lives of Armenian genocide survivors become more visible, we realize that every Armenian is more than just a document, every story of survival is a work of art. A history in which family letters are more widely read, personal stories of survival are more honored and more easily passed on to new generations, helps us understand which reality we are part of.