After the Armenian Genocide resolution was passed, German government also recognized what happened in Namibia as genocide. We talked to Prof. Jürgen Zimmerer from Hamburg University, who has been studying Herero Genocide.

German

government recognized the massacre of the Herero and Nama people of

Namibia by German troops between 1904 and 1908 as genocide. This

massacre is

referred as genocide in an official document of the government for

the first time. Left-wing politician Niema Movassat's request was

published in "Frankfurter Rundschau". In

a response to the request, German government acknowledged that the

massacre in Namibia, in which more than 100.000 people were killed,

was genocide.

Niema Movassat also demanded information about the unofficial meetings between the representatives of Germany and Namibia. Germany's special envoy for the dialogue between Germany and Namibia Ruprecht Polenz defined the purpose of the meetings as “increasing the cooperation with a common understanding of the past.”

We talked to Prof. Jürgen Zimmerer from Hamburg University, who has been studying Herero Genocide.

Could

you please briefly tell what the Herero Genocide is?

Since 1884 Germany had 'possessed' colonies in Africa (and in the Pacific), the most important being Cameroon, Togo, German East Africa and German Southwest Africa. In the latter (what is today Namibia) in 1904 the Herero nation (and later the Nama, too) resisted German invasion and occupation, particularly accelerating disenfranchisement and dispossession. Germany, which was brought to the brink of defeat sent reinforcements from Germany under the notorious general Lothar von Trotha, who believed history to be a 'race war' between the 'White' and the 'Black' race, and who conducted the war accordingly. After the failed Battle at the Waterberg, the Herero nation, including women and children fled eastwards into the waterless Omaheke desert. German troops pursued them and pushed them even further. On order by general von Trotha they blocked access to the waterholes, thereby condemning the Herero to death by thirst. Thousands perished. When this policy was rescinded after more than two months, the survivors were put into concentration camps and subjected to forced labour. In some of those camps 'annihilation through neglect' was continued. After the Nama joined the war the German army waged are war of annihilation against them, also targeting women and children. An estimated 70-80 percent of the Herero and 50 percent of the Nama were annihilated. Their land was confiscated and sold to German settlers, a source of the uneven distribution of land up to today.

Despite the absence of an official act, can we say that Germany acknowledged that it committed Herero and Nama Genocide?

There is not yet an official act by parliament, but everything is leading in this direction. Leading members of parliament including the Speaker of the House, Norbert Lammert, are advocating this as it the leader of the Green Party, Cem Özdemir. The German government has now given up its refusal to apply the term of genocide to the Herero case in official documents, and it is now official policy to do so. An official recognition by parliament and an apology by the German president is expected for next year. There are currently negotiations being held with Namibia about the exact wording, the timing and the consequences.

What is the importance of that declaration?

Since Germany sees itself in the legal and national tradition of the former German Empire (1871-1918) it is important that the ultimate sovereign, that is the German people, represented by its parliament, acknowledges the historical responsibility. The German parliament has done so with its Armenian Resolution on 2nd June 2016, acknowledging also German responsibility as main ally of the Ottoman Empire during World War I. Now following suit with a Herero and Nama resolution is inevitable in order to avoid the accusation of applying double standards.

Which steps can Germany take about the Herero Genocide from now on?

Currently there are negotiations under way between the German and the Namibian government about the form of the apology, the exact wording and also issues such as reparations. Whilst the German government rejects any legal obligation to pay reparations, it is apparently willing to found and finance a "foundation for the future", which will organise youth exchange programs or other projects.

Germany has been accused of taking political steps after passing the Armenian Genocide Resolution. However, pursuant to that declaration, is it possible to say that Germany is genuinely trying to confront its past?

Germany has a long track record of facing up to its 'dark' past, namely the Holocaust and other crimes of the Third Reich. There are numerous programs to educate especially young people about the crimes. There are monuments at central locations, i.e. in Berlin, and numerous former concentration camps offer educational programs. And it is also part of the school curricula. So there are many attempts to come to terms with its history. It is not hidden, it is out in the open. This now needs to be extended to include also other instances of genocide and crimes against humanity, for example in the colonial context. This is also an important step to combat racisms, which raises its ugly head again.

What is the role of the law regarding the Armenian Genocide in initiating this step concerning Namibia?

The Armenian Resolution brought the recognition of the Herero and Nama genocide back on the agenda. Many people realised that one should recognize this colonial genocide, which preceded the fate of the Armenians by a decade, as well, in fact should have done it prior.

Would this step pave the way for other European powers to acknowledge their colonial crimes?

This seems to be one of the reasons why the discussion about the Herero and Nama genocide is so closely observed internationally, because it would increase pressure on other former colonial powers to follow suit. There are debates about coming to terms with a racist colonial past in many European countries as well as in the USA, Canada, Australia or New Zealand, and pressure mounts. So far Germany has come closest to accept colonial genocide to have happened. However the process is still open.

It

is also not limited to the question of genocide, but to the

importance of colonialism for the shaping of the modern world today.

As first major European city, the City of Hamburg has announced to

officially deal with "Hamburg's (post-)colonial memory" in

2014. It has set up a collaborative research project on that topic

and develops ways to commemorate this past adequately.

Extermination plan of

General Lothar von TrothaAccording

to UN's documents, the first genocide of 20th century was

carried out in today's Namibia between 1904 and 1908 by the order of

German General Lothar von Trotha. Becoming an issue of debate with

the independence of Namibia in 1990, Herero Genocide is a result of

colonialist policies. Rebelling against the order of slavery

established by German colony, Herero people led by Chief Samuel

Maharero and Nama people with the order of King Hendrik Witboii took

up arms against German forces. After the uprising started, the

German central government sent in a troop consisting of 14,000 under

the command of General Lothar von Trotha.

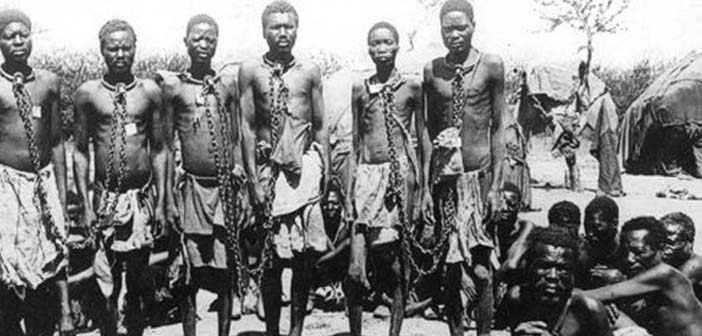

With

the special plan of the General, Herero people were chased to

Kalahari desert and kept away from water sources. Between 1904 and

1908, the ones who survived from the death traps of the General were

sent to concentration camps and used as slave laborers.

Majority of Herero people in the camps died of disease, abuse, and

exhaustion. Later, it turned out that mortality rate in camps was

69-74%. Similar to the practices of Holocaust, the ones who were sent

to the camps were tattooed and forced to wear neck-bands that reveal

their identity when they were outside the camp for working.

In April 1905, General von

Trotha started an extermination policy against Nama people, which was

another ethnic group living in the region. Sending a letter to Nama

people, the General urged them to surrender and stated that otherwise

they will be shot and exterminated. As a result of the massacres,

10,000 Nama people were killed and 9,000 were sent to camps.In 1933, Nazi regime came

to power and named a street in Munich after General von Trotha. In

2006, the name of the street was changed to “Herero Street”, in

the memory of the victims.

After a year, the family of General von Trotha visited Omaruru upon the invitation of Herero chiefs. Wolf-Thilo von Trotha, a grandson of the general, said, “As von Trotha family, we are deeply ashamed by the horrible events that took place 100 years ago. At that time, human rights were gravely violated,” and apologized to Herero people on behalf of his family for the actions of his grandfather.