Sonsuzluğa giden bir trende asılı kalmış çocukluk

‘Kimsin sen? Hiçbir yere ait değilsin.

Yersiz yurtsuz… Varlığın bir misafir gibi yaşamaya

daha ne kadar devam edecek?

Her şey fazla sessiz. İçi taşla doldurulmuş bir kuyu gibi...

Bildiğimden fazlasını hatırlıyorum… Hayal gücüm hafızamdan daha geniş. Dağılıp gitmiş ailemin kırık kalıntılarından daha fazlasını gördüm.’

Özcan Alper’in son filmi ‘Rüzgârın Hatıraları’nın başkarakteri Aram’ın iç sesi olan bu dizeler, büyük felaketlere ve acılara tanık olmuş, baskı ve şiddet görmüş, sürgün edilmiş, yersiz yurtsuz kalmış Ermenilerin ve hatta belki tüm halkların ortak çığlığı. İkinci Dünya Savaşı’nın karanlık günlerinde, yazar ve ressam Aram, Varlık Vergisi Kanunu’nun ardından, siyasal baskıların da etkisiyle, Türkiye’den kaçmak zorunda kalır. Sovyet Gürcistanı sınırında bir köyde, ormandaki bir kulübede, 1915’e, çocukluğuna ve yaşadığı travmaya döner. Hafızasının derininde sakladığı yüzleri anımsamaya ve çizmeye başlarken, seyirciye de iç sesiyle duyurur çığlığını.

Onur Saylak, Mustafa Uğurlu ve Sofia Khandemirova’nın başrolleri paylaştığı film Antalya Film Festivali’nde, ‘Uluslar Arası En İyi Film İzleyici Ödülü’ne ve

‘En İyi Müzik Ödülü’ne layık görüldü; Andreas Sinanos da bu filmdeki çalışmasıyla ‘En İyi Görüntü Yönetmeni Ödülü’nü aldı. Özcan Alper’le,

11 Aralık’ta vizyona girecek olan ‘Rüzgârın Hatıraları’nın oluşum sürecini ve felaketin temsil edilmesi meselesini konuştuk.

Filmin hikâyesiyle başlayalım. Aram Pehlivanyan’ın hayatından esinlenerek yazdığınız senaryonun oluşum sürecini anlatır mısınız?

‘Gelecek Uzun Sürer’ filmini yeni bitirdiğimiz bir dönemdi. Bazen bir şiir, bir kitap, bir durum sizi tetikleyebiliyor. Benim için edebiyat ihtiyaç değil, hayatımın bir parçası oldu hep. Kitapları karıştırırken, Aram Pehlivanyan’ın ‘Özgürlük İki Adım Ötede Değil’ kitabına denk geldim. 1940’ların entelektüel kuşağına, Abidin Dino, Yaşar Kemal, Sabahattin Ali, Rıfat Ilgaz gibi isimlerin eserlerine ve hayatlarına özel bir ilgim vardı. O dönemin sosyalist hareketi ve edebiyatçıları içerisinde, azınlıklarla ilgili çok az şey yazıldığını, konuşulduğunu biliyoruz. Aram Pehlivanyan’ın hayatında, sürgün olduktan sonra şiir yazamama hali beni çok sarstı. Sosyalist mücadele içerisinde daha aktif hale geldikten sonra iyi bir şairin şiir yazamama hali üzerine düşündüm. Vartan ve Jak İhmalyan’ın hayatına, Nazım Hikmet’in o dönemki şiirlerine, Sabahattin Ali’nin romanlarına baktım. O dönemin totaliter ve otoriter sistemi içerisinde, özellikle savaş koşullarında, entelektüellerin hayatında başka türlü bir içsel sürgünlük olduğunu farkettim. Edebiyatta, Birinci ve İkinci Dünya Savaşı’nı görmüş bir kuşak vardır, ‘Kara Kuşak’ deriz. Pehlivanyan’ın yanı sıra, o dönemin birçok entelektüelinden etkilenerek yarattığım karakter yazar ve ressam Aram, 1943’te Ermenice-Türkçe bir dergi çıkarıyor. Dolayısıyla, Aram’ın, o yıllarda 35-40 yaş arasında olduğuna karar verdim. Geriye doğru gidince, 1915’te 10 yaşlarında olan bir çocuğun 1915’e dair travması, geçmişi ortaya çıkmaya başladı. O dönemin Ermeni yazarları, çizerleri, Ermeni komünistleri ve sosyalistleri üzerine eğilmeye başladım. Sürgünlük, evsizlik, yersizlik yurtsuzluk, sınırda kalma, bugün mültecilerin yaşadığı durum gibi hayat boyu insanın ev arayışı, ölümle karşı karşıya kalma, tehcirler, soykırımlar, ölümle yüzleşme çabası, bu filmin sacayaklarını oluşturdu.

Filmde, Aram’ın 1915’te yaşadıklarını hafızasının gerisine itmesi, köyde yanına sığındığı Mikail’e kendini ‘Ahmet’ olarak tanıtması, içinde bulunduğu sosyalist ortamın bir dayatması olabilir mi?

Aram Pehlivanyan 1979’da öldüğünde komünist arkadaşlarının onu Ahmet Saydam olarak anması, bu coğrafyadaki eksikliğe parmak basıyor. Ermeni Soykırımı’na ilişkin, Türkiye sosyalist hareketinin, Sovyetler Birliği’nin, tüm dünya ülkelerinin de tutumunu biliyoruz. Herkes kendi politik çıkarını düşünüyor. Çünkü Soykırım’ın büyük bir iktisadi tarafı var. Soykırım’dan elde edilen paralar, Tehcir’i planlayanlardan Osmanlı’nın müttefiki Almanya’ya aktarılıyor, sonra o paraya İngiltere el koyuyor. Batı tıpkı bugünkü Suriyeli mülteci krizinde olduğu gibi önce kendi ekonomik çıkarını düşünüp felaketin üstünü kapatmaya çalışıyor. Sovyetler Birliği de Türkiye’yle sorunsuz bir komşuluk ilişkisi kurmak için genç Sovyet Ermenistanı’nın kafasına vurup, konuyu orada bile konuşturmuyor. Türkiye sosyalist hareketi, Sovyetler üzerinden oluştuğu ve kendi öz bilincini yaratamadığı için, 1915’in felaketine ilişkin sessiz kalıyor. Vedat Türkali, ‘Güven’ romanında bu konuda bir nevi özeleştiri vermiştir. Hrant Dink’e verdiği bir röportajda da, Türkali, Türkiye sosyalist hareketinin Soykırım’la yüzleşmediğini belirtir.

Aram’ın sessizliği, Soykırım’a tanık olup suskunluğa gömülmüş Ermeniler açısından ne söylüyor?

Ermeniler açısından iki nedeni olabilir. Büyük bir felaketin ardından, kurtulanlar, darmadağın olmuş hayatlarını kurma çabasında oldukları ve zorluklarla boğuştukları için dönüp geçmişe bakamıyorlar. Bu noktada, Marc Nichanian’ın, Ermeni Soykırımı üzerinden, felaketin edebiyatta ve sanatta dile getirilebilmesi, tanıklık etme, tanıklığın biçimi üzerine kaleme aldığı ‘Edebiyat ve Felaket’ adlı kitabı benim başucu kaynağım oldu. Bir de Primo Levi’nin ‘Boğulanlar Kurtulanlar’ kitabı... Levi, Holokost’tan kurtulan, ömrü boyunca tanıklık etmek için yazıp, 67 yaşında tanıklığı ve geçmişte yaşadıklarını taşıyamayıp intihar eden biri... Levi, oradan kurtulabilenlerin esas tanık olmadığını, tanıkların orada ölmüş olduğunu söylüyor. Walter Benjamin’in intiharını, Avrupa’dan kaçıp süregiden Nazi vahşetine artık tanık olmak istemeyen, Latin Amerika’nın vahşi ormanlarında karısıyla ölüme giden Stefan Zweig’ın hayatını biliyoruz.

Ermeniler konuşmuyor, çünkü yeni kuşağa zarar gelmesinden korkuyorlar. Bir de, bu kadar ağır bir şeyi anlatmak nasıl mümkün olabilir? Hrant Dink Vakfı Yayınları’nın sözlü tarih kitaplarından birinde bir hikâye var. 1960’ların sonunda kadın, babasının hikâyesini ses kaydına anlatmasını istediğinde, baba uzun süre konuşamıyor. Sessizlik çığlığın kendisi aslında. Aram karakteri, bir noktaya kadar geçmişini bastırıyor. Aynı şiddet ve sürgün olma haliyle karşı karşıya kaldığında, yavaş yavaş geçmişin tekrar bilincine çıktığını görüyoruz. Geçmiş asla geçmiş değildir, kapıdan kovsan bacadan gelir. Türkiye toplumu 1915’i konuşamadığı için bugün Kürt meselesi var.

“Felaketin kendisini anlatmak imkânsızsa, farklı bir gerçeklik yaratmak gerekir. Ressam olan Aram’ın hafızasında yüzler kaldığını düşündüm. Kişisel hafıza ile toplumsal hafıza arasında bağ kurmaya çalıştım.”

Aram, ormanda yalnız kaldığında, Der Zor çöllerinde gördüğü yüzleri yavaş yavaş anımsamaya başlıyor. Hafıza ve hatırlama üzerine nasıl bir çalışma yaptınız?

Sadece Ermeni Soykırımı’yla ilgili değil, Saraybosna, Endonezya, Latin Amerika’daki darbe dönemi, pek çok toplumsal travmalar, felaketler, soykırımlar üzerine, bu durumlarda toplumsal bellek ve hafızanın oluşumuna dair okumalar yaptım. Aram’ın psikolojisine yoğunlaştım. Aynı zamanda, bir nevi antropolojik kazı yaptım diyebilirim. İşin estetik tarafıyla birlikte hatırlama biçimleri üzerine düşündükçe, böyle bir karakterin, edebiyatta sıkça kullanılan bilinç akışı yöntemiyle geçmişe dönebileceğine karar verdim. Virginia Woolf, Adalet Ağaoğlu gibi yazarların edebiyatta kullandığı bu yöntem sinemada nasıl mümkün olabilirdi peki? Burada rehberim yine Nichanian’ın kitabı oldu. Felaketin kendisini anlatmak imkânsızsa, farklı bir gerçeklik yaratmak gerekir. Ressam olan Aram’ın hafızasında yüzler kaldığını düşündüm. Aram, travmanın kendisiyle yüzleşmeye başladıkça, çocuklar ve yaşlı kadınların yüzlerini hatırlamaya başlıyor. Soykırım’da kaybettiği babasını, kız kardeşinin yüzünü hatırlıyor. Kritik nokta şu: Herkesin yüzünü hatırladığı halde, annesinin yüzünü hatırlayamıyor. Aram için oradan kurtulmuş olmak, büyük bir sevinç ya da yaşama arzusu ifade etmiyor, zoraki bir hayata tutunmaya tekabül ediyor. Hayatta kalmanın getirdiği büyük bir suçluluk var. Toplumsal travmanın içinde Aram’ın da kendi içsel travması var. Filmde kişisel hafıza ile toplumsal hafıza arasında bir bağ kurmaya çalıştım.

Aram’ın annesine ilişkin hatıraları, kadınlarla ilişkisini nasıl etkiliyor?

Büyük bir felaketten kurtulan bir çocuk olarak, anne imgesi hayatı boyunca onu terk etmiyor. Aram’ın geçmişini yazarken, annesiyle ilk yüzleşmesini sağlayana kadar kadınlarla bir problemi olduğunu düşündüm.

Aram’ın babasını Konya’dan yola çıkan trende görüyoruz. Babasının Aram’ın hayatında nasıl bir etkisi var?

Babayı sadece trende ve sislerin arasında ona ateş edilirken görüyoruz. Sonradan çıkardığım bir sahne var. Baba tek bir şey söylüyordu ve o söz, Aram’ın hayatında belirleyici oluyordu. Bir nevi, vasiyet cümlesi gibiydi. “Kin tutma ama unutma, çiz” diyordu. Didaktik olabileceği düşüncesiyle çıkardım. Baba filmde söz söylemese de, Aram’ın herşeye rağmen hayatta kalma ve devam etme mücadelesinde etkili oluyor. “Babam kırık bir sesti” diyor bir yerde...

Filmde özgürlüğün simgelerinden olan doğanın da Aram için bir hapishaneye dönüştüğünü görüyoruz.

Dönemin Alman romantiklerinin başında gelen ve filmde de kitabını gördüğümüz Heinrich Heine ve o dönemin politik sürgünleri eserlerinde doğayı romantize eder. ‘Sonbahar’ filminde içsel bir anlatıma destek veren doğanın, öyle özgür bir alan olmadığını, Aram için geçmişin hatıralarına hapsolduğu bir yere dönüştüğünü görüyoruz.

“Marc Nichanian’a göre, Soykırım’ı ispat etmeye çalışmak, inkâr edenlerle aynı düzleme düşmek anlamına geliyor. Soykırım’ın filmi veya romanından öte, kültür ve varlık olarak geçmişi bugüne taşıyan filmler yapmak gerekiyor.”

Soykırım’ın 100. yılında, felaketi anlatan filmlerin ve eserlerin sayısının azlığı tartışılıyor. Siz ne düşünüyorsunuz?

Soykırımın filmi ve kitabı tartışmasının dışına çıkmak gerektiğine inanıyorum. Nihayetinde, fiziksel soykırım büyük bir kültürel soykırıma da neden oldu. ‘Sonbahar’ filminin İsrail’de birkaç gösterimi yapılacaktı. Önder Çakar’la birlikte gittik. Kudüs’te dünyanın en büyük Ermeni kütüphanelerinden biri var. Hemşin tarihi üzerine araştırmalar yapmak istediğim için kütüphaneyi ziyaret etmek istedim. Adını hatırlayamıyorum ancak soyadı Hintliyan olan biri bize kütüphaneyi gezdirdi. Ben Hemşin Ermenicesiyle konuşmaya başlayınca şaşırdı. Sonra kaç kişi öldürüldü meselesine gelindi. Hintliyan, bize kocaman bir salonun ortasından demir kapı açtı, sonra bir iç kapı daha... Önümüzde binlerce kitap vardı. Hintliyan, “Bunlar 1915’ten önce Anadolu’dan kurtarılan kitaplar... Şu an dünyanın her tarafına dağımış Ermeniler var. Ama 100 yıl sonra, şimdi toplasanız, şu kitapların onda biri edecek üretim yok. Benim için soykırım budur” dedi. Marc Nichanian’a göre, Soykırım’ı ispat etmeye çalışmak, inkâr edenlerle aynı düzleme düşmek anlamına geliyor. Soykırım’ın filmi veya romanından öte, kültür ve varlık olarak geçmişi bugüne taşıyan filmler yapmak gerekiyor. Benim filmim, 1940’lı yıllarda geçiyor, 1915’i hatırlamalarla görüyoruz. Geçmişten bize kalanın duygusuyla yaptığım bu film, bugünü de anlatıyor.

Az diyaloğun olduğu filmde, Aram’ın iç sesleri ön plana çıkıyor. Bunu tercih etmenizin nedeni nedir?

Edebiyattan farklı olarak, sinemada mümkün olduğunca minimal konuşma ve diyaloğun daha anlamlı olduğunu düşünüyorum. Esas olan sinematografik ve görsel dil. Aram yaptığı işlerle kendini ifade eden biri. Sessizliğin kendisi onun dili. Travmadan dolayı geçmişi bilinçaltına itiyor. Bir yerden sonra bunları yazıya dökmek, kaydetmek ve günlük tutmak istiyor. Bu noktada iki metot denedik. Türkiye’nin en iyi genç öykücülerinden Ahmet Büke’yle çalıştım. Ahmet’e, ‘Bir edebiyatçı olarak bugün sürgün olsaydın, kaçmak zorunda kalsaydın, dağ başında olsaydın, günlük tutsan ne yazardın?’ dedim. Ahmet böyle bir günlük tuttu. Sonra bu günlüklerden bazı kısımları senaryoya dahil ettim. Aram’ın iç dünyasını dışarıya çıkarma ve seyirciyle paylaşma noktasında iç sesleri kullanmaya karar verdik. Daha imgesel bir dil kullanan biriyle çalışmak istedik. Bülent Usta’nın Birgün’deki yazılarını çok şiirsel buluyordum. Bülent, konuyla ilgili 50’ye yakın kitap okudu. Hem süreci anlatıp, hem de çok az konuşmayla nasıl aktarabilirdik? Damıtarak yaratmamız gerekiyordu. Bülent çok büyük emek harcadı. Filmi her izlediğimde, Aram’ın iç seslerinde tüylerim diken diken oluyor.

Filmde, ‘Yok bir şey’ cümlesini her karakterin ağzından duyuyoruz. Bu cümle, toplumsal hayatımızda hangi suskunluklara tekabül ediyor?

Senaryo ilerledikçe, karakterleri konuşturdukça, tüm karakterlerin birbirlerine çok şey söylemek istediğini ancak farklı nedenlerle sustuklarını fark ettim. ‘Yok bir şey’, toplumsal travmaların, yüzleşme mevzularının cisimleşmiş hali gibi filmde. Kişisel hayatımızda, açıkça konuşup kolayca halledebileceğimiz şeyleri hasır altı ediyoruz. Bunu farkına varırsak, hem kişisel hem toplumsal olarak yeni bir sayfa da açabiliriz diye düşünüyorum. Antalya’da bir seyirci, filmden sonra kendi hayatını, çocukluğunu, anne ve babasıyla ilişkisini sorguladığını söyledi. Filmin politik ve tarihsel katmanının yanı sıra bugüne dair, kişisel durumla ilgili algılanması benim yapmak istediğim şeye denk geliyor.

Fatih Akın’ın ‘Kesik’ filmini Türkiye’de sadece 20 bin kişi izledi. Tarihsel bir trajediyi anlatan filme, hem Türklerin hem de Ermenilerin mesafeli yaklaşmasıyla ilgili ne düşünüyorsunuz?

Fatih Akın’ın bir izleyici kitlesi var. Ancak film çıkmadan burada bir linç kampanyası yapıldı, kısmen de başarılı oldu. Film dağıtımcılarının çoğunun korkup dağıtmak istemediklerini düşünüyorum. Bir Türk yönetmenin 1915’le ilgili film yapması çok önemliydi. Ermenilerin ilgisinin az olmasını geride kalanların ruh hali üzerinden konuşabiliriz. Öte yandan, Türkiye’de genel bir tin var. Bireysel olarak çıkışlar olsa da, Ermeni, Türk, Rum, solcu, sağcı fark etmez, herkes bu ortak tinden nasibini alır. Türkiye’deki Ermenilerin de farklı kültürel kodlarla büyüdüğünü düşünmüyorum. Kimliğini saklayıp politikadan uzak durmaya çalışan, ortalama bir gündelik hayatın derdine düşmüş bir çoğunluktan bahsedebiliriz. Ama şimdi yeni bir kuşak var ve bunu yıkmak istiyor.

Şiddettin temsil meselesi Fatih Akın’ın filminde de tartışılmıştı.

Fatih Akın’ın filmini çok önemsiyorum. Hiçbirşey okumamış dahi olsak Holokost’la ilgili çok imgeye sahibiz. Ermeni Soykırımı konuşulmamış ve görsel hafızası az olduğu için, ‘Kesik’ gibi bir film yapmak büyük cesaret ve zor. Türkiye’de Ermeni Soykırımı’nın ilk görsel hafızasını kaydeden film olarak da anılacak hep.

Nichanian’ın dediği gibi, felaketin doğrudan canlandırmaya çalışmak mümkün olmayacağı için, sanatsal soyutlama düzeyinde anlatmak gerekiyor. Ben de bir ressamın hatırladıkları üzerinden anlatmayı seçtim. Önceki iki filmim, ‘Sonbahar’ ve ‘Gelecek Uzur Sürer’ için de eleştiriler gelmişti. ‘Neden o ağır şiddeti ve politik atmosferi göstermiyorsun?’ diyenler oldu. O şiddeti her gün televizyonda görüyorsun. Şiddeti yeniden üretmeye çalışıp, şiddetin pornografisini yaratmaya gerek olmadığına inanıyorum.

‘Bir aradalığı gelecekte mümkün kılmanın yolu yas tutmaya saygı’

Filmle ilgili yaptığınız araştırmaların sizin için de bir öğrenme süreci olduğunu dile getiriyorsunuz. Bu süreçte, sizi en çok şaşırtan ne oldu?

Nichanian, kitabında Homeros’un İlyada’sından bir örnek veriyor. Hektor ve Akhilleus arasında geçen bir konuşma var. Hektor, kim öldürülürüse öldürülsün, bedenine saygı gösterilmesini, köpeklerin insafına bırakılmamasını, cesedin yas töreni yapacak yakınlarına teslim edilmesini istiyor. Bir aradalığı gelecekte mümkün kılmanın tek yolunun yas tutmaya saygı olduğunu, barışmanın yas olgusuyla doğrudan bağlantılı olduğunu gösteriyor bu anlatı. Yıllarca okuduğum bütün kitaplardan öte, bu hikâye, Türkiye’deki soykırımın inkârı, devletin ve halkların tutumunu özetledi bana. Hakkâri’de bedeni yerde sürüklenen Hacı Lokman Birlik, Rojava’da savaşan Aziz Güler’in cenazesinin bekletilip ailesine verilmemesi, tam da bu sistemin ve devletin, kendilerince İslamcı Müslüman kimliklerine rağmen, 1915’ten bugüne kadar, çoğul olandan tekil olana kadar, en büyük şiddeti ve eziyetin nasıl sürdürdüğünün göstergesi. Bu anlatı, beni hem umutsuzluğa sürükledi, hem de rejimin karakterini anlamak için kilit hikâye oldu. Ermeni toplumunda böyle bir travma var. Senin yok edilmenden öte, seni yok edenin ölüne saygısı yok, üstelik yas tutmanı engellemeye çalışıyor. Homeros’un iki bin yıl önce ifade ettiği durum bugün de devam ediyor.

Film için, sinema salonu bulmakta zorlanıyor musunuz?

Sinemaların bir tekelleşme durumu var. On salonu olan sinemanın sekiz salonunu bir film kapatabiliyor. Avrupa’daki gibi bağımsız sinema salonlarının olması lazım. Bunu sosyal demokrat belediyeler bile yapmıyor. HDP belediyeleri belki yapabilirdi, ancak böyle bir ortamda siyasetten sanata nasıl vakit bulacaklar? Ben filmim için, Bakırköy gibi bir yerde sinema salonu bulamadım.

Politik filmler, önyargılar ve inkâr süreçlerinden bağımsız olarak izlenip algılanabiliyor mu sizce?

Yüz yıl geçmesine rağmen Soykırım’ı kabul etmek bir yana, hem devlet hem toplum olarak insanların yas tutmasını normal görmüyorsan büyük bir sorun var. Edebiyat ve sanat da bu genel tinin dışında değil. ‘Rüzgârın Hatıraları’nın yapım sürecinden, Türkiye’deki bazı festivallerin filme karşı tutumuna kadar, üstü kapalı da olsa, bir şekilde sansürün yaşandığını hissediyorum. Baskı ve önyargılardan ziyade bir sanatçı için en tehlikeli şey oto sansür uygulamak. Ben filmi kendime karşı sorumluluk hissettiğim için yaptım.

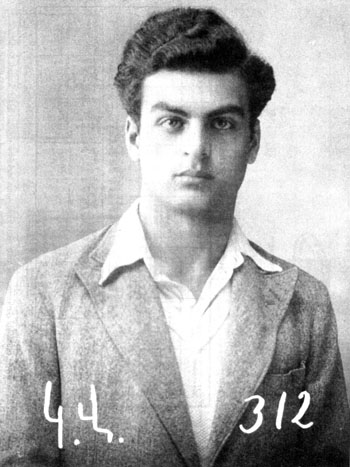

Özcan Alper, filmin baş karakterini Aram Pehlivanyan’ın hayatından esinlenerek yaratmış. Pehlivanyan, Üsküdar’da, 1917’de dünyaya geldi. Nersesyan-Yermonyan ve Getronagan’ın ardından İstanbul Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi’ni tamamladı. Daha lisedeyken şiir yazmaya başladı. Üniversite yıllarında siyasi faaliyetlere katıldı, 1941’de tutuklandı ve 15 ay hapis yattı. 1945’te A. Aliksanyan ve Sarkis Keçyan ile birlikte çıkardıkları ‘Nor Or’ (Yeni Gün) gazetesi, 1946’da sıkıyönetim kararıyla kapatıldı ve Pehlivanyan üç yıl hapis yattı. 1950’de ‘Grung’ (Turna) edebiyat dergisini çıkardı, ancak derginin ikinci sayısını basamadan, askerliği Erzurum’a tertip edilince, İstanbul’u terk etti. ‘Bizim Radyo’da redaktörlük ve Türkiye Komünist Partisi’nde politbüro üyeliği yaptı. 1979’da Berlin’de yaşamını yitirdi. Ermenice ve Türkçe şiirlerinden oluşan ‘Özgürlük İki Adım Ötede Değil’ adlı kitabı, 1999’da Aras Yayıncılık tarafından yayımlandı.