In fact, Turkish policy in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean is conditioned by the collapse of the regional security architecture, and power vacuum left behind.

Only a decade ago, Turkey’s foreign policy was to come out from its regional isolation by improving relations with neighbours. Its former foreign minister Ahmed Davudoghlu had even coined a slogan for the occasion: “zero problems with neighbours”. Turkish foreign ministry website still chants the merits of this policy: “Aware that development and progress in real terms can only be achieved in a lasting peace and stability environment, Turkey places this objective at the very center of her foreign policy vision. This approach is a natural reflection of the ‘Peace at Home, Peace in the World’ policy laid down by Great Leader Ataturk, founder of the Republic of Turkey.”

This doctrine aimed at active foreign policy to solve problems Turkey had with its neighbouring countries. The site mentions “multidimensional dialogue process with Greece since 1999”, as well as other states sharing common borders with Turkey. “Turkey believes that the positive results of ‘zero problems with neighbours’ approach which we started to witness even today will be seen further first in our region and ultimately at a global scale, like eventually broadening rings that a stone thrown into still water creates” – one could still read on the foreign ministry web page.

But these days the stones thrown by Ankara are not just causing rings, but violent waves. Turkey seems to be engaged in all directions, not in dialogue but in wars and aggressive geopolitical competition. Turkish armies are carrying out daily attacks against Kurdish armed opposition in the southeast, as well as in northern Syria and Iraq. Its military are also fighting in Libya, far away from their bases, in a risky endeavour for uncertain objectives. Following the border clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan in July, Turkish officials made threats against Armenia, an ally of Russia, and sent their soldiers including military helicopters to Azerbaijan for joint war games. Add to this Turkish claims to large parts of east Mediterranean as well as Aegean and Black Seas, with potential offshore gas reserves that Ankara labels to be part of its “Blue Homeland”.

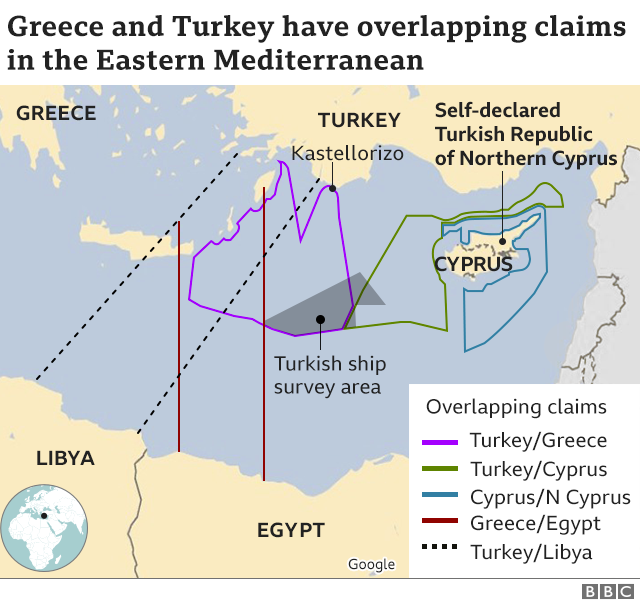

The only problem is that parts of this area are claimed by Greece, Cyprus, and Egypt. After coming close to war with Syria and potentially Russia last winter, and massive intervention in Libya that led to important military successes, Ankara has launched another geopolitical challenge: domination over eastern half of the Mediterranean. The stakes of the latest Turkish geopolitical offensive are high; access to offshore natural gas deposits in the eastern Mediterranean. Turkish claims of a “Blue Homeland”, a maritime exclusive zone of 462’000 km2, half the surface area of Republic of Turkey is indeed ambitious. This assertive policy of Ankara coincides with an interest in exploring for hydrocarbons, in which Turkey invested intensively since 2017, following serious tensions with Russia its major energy supplier. In 2019, Turkey spent $41billion on energy imports, a major burden for an indebted economy.

In November 2019 Ankara and Tripoli signed a maritime boundaries accord with the Tripoli government, which cuts the Mediterranean in half. It triggered an immediate reaction from Egypt, which declared the agreement “illegal”, and from the Greek foreign minister who remarked that the accord “ignores that between those two countries there is the large geographical land mass of Crete”.

Turkey became increasingly bold in its declarations and actions, after its massive support of Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA) led to military victories in western Libya. “The vital role Turkey has played in Libya and against warlord Khalifa Haftar has given Ankara a louder voice when it comes to the battle for supremacy in the Eastern Mediterranean” according to an article by Turkish Radio Television (TRT). The discovery of an important offshore gas-field in the Black Sea with estimated 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas, could be a major breakthrough, reducing Turkish imports starting form 2023, and sharpen further the on-going geopolitical competition.

Opportunity as Strategy

How could Ankara make such a radical 180 degree shift in its foreign policy while the same AKP party remains in power? The shift can only be explained by abandoning the strategic vision of Davutoghlu, and instead to follow a pragmatic power policy. Inside Turkey, the policy of solving the Kurdish problem through dialogue, reforms, and recognition of Kurdish rights was replaced by the old policies of repression because it was possible and because it was expedient: it plays into populist nationalism of Turkish masses and mobilizes them behind the president. The collapse and fragmentation of the Iraqi state and later Syrian state, created a power vacuum to the south of Turkish borders, giving Ankara an opportunity to expand towards Aleppo, Mosul and Kirkuk, old Ottoman garrison towns that excite expansionist imagination of Turkish nationalists. Donald Trump’s unclear policy towards Kurdish forces in Syria created another opportunity for military intervention there. The civil war in Libya was an opportunity to project power across the Mediterranean.

In fact, Turkish policy in the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean is conditioned by the collapse of the regional security architecture, and power vacuum left behind. With Trump in Washington, US and NATO policies are incomprehensible. The European Union is a book of contradictions: in Libya, while Italy and Malta actively support Turkey and GNA, France and Greece support Haftar’s camp. The same can be said concerning Greek-Turkish rivalry; while France has actively supported EU member Greece, while Germany remains ambiguous, proposes “mediation”, and continues to support its traditional ally.

Taking Risks

Opportunistic policies do not add up into a strategy. Turkey might have taken too many has spread out its forces above its real means. It has provoked too many rivals, which could cause a strong backlash. On June 10, French authorities announced that frigate Courbet was targeted three times by fire control radars of a Turkish warship off the coast of Libya. The French frigate was in a mission to control a cargo ship, which was escorted by three Turkish navy vessels, as part of an international operation to impose arms embargo on Libya. The incident angered French President Emmanuel Macron. On August 12, Turkish Greek frigate Limnos collided with the Turkish warship Kemal Reis, which was escorting a Turkish exploration ship in maritime waters claimed by Greece. Kemal Reis was damaged and suffered a large hole in its hull.

Its war against the Kurdish armed opposition, and continuous operations across its southern borders could spill-over and cause a major conflict: on August 11 Turkish drones attacked inside Iraq, killing two Iraqi officers who were at a meeting with PKK officials.

On the diplomatic front, in early August Greece and Egypt signed an agreement on an exclusive economic zone in the eastern Mediterranean. This agreement challenges the earlier agreement between Turkey and Libya. France also called Turkey to stop oil and gas exploration in disputed waters.

Constant Turkish provocations against France and Greece, threats to send refugees to Europe, military interventions in Libya, Syria and Iraq, plus its internal struggles against Kurdish forces, is a tall list. Simultaneously, Erdogan has problematic relations with an army accused of a coup in 2016, with thousands of officers arrested or purged. In the middle of a financial crisis with the devaluation of the national currency, one of the largest current account deficit, and shrinking of foreign reserves, how long can Ankara afford its foreign policy ambitions?

A decade ago Turkey projected its foreign policy through active but soft power approach. Now, Turkey seems to be at war in all directions. It is time to revise the old slogan: “War at Home, War in the World.”